Canon law is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law, or operational policy, governing the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches, and the individual national churches within the Anglican Communion. The way that such church law is legislated, interpreted and at times adjudicated varies widely among these four bodies of churches. In all three traditions, a canon was originally a rule adopted by a church council; these canons formed the foundation of canon law.

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Different religious systems hold sacred law in a greater or lesser degree of importance to their belief systems, with some being explicitly antinomian whereas others are nomistic or "legalistic" in nature. In particular, religions such as Judaism, Islam and the Baháʼí Faith teach the need for revealed positive law for both state and society, whereas other religions such as Christianity generally reject the idea that this is necessary or desirable and instead emphasise the eternal moral precepts of divine law over the civil, ceremonial or judicial aspects, which may have been annulled as in theologies of grace over law.

In Christian theology, ecclesiology is the study of the Church, the origins of Christianity, its relationship to Jesus, its role in salvation, its polity, its discipline, its eschatology, and its leadership.

Ecclesia Dei is the document Pope John Paul II issued on 2 July 1988 in reaction to the Ecône consecrations, in which four priests of the Society of Saint Pius X were ordained as bishops despite an express prohibition by the Holy See. The consecrating bishop and the four priests consecrated were excommunicated. John Paul called for unity and established the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei to foster a dialogue with those associated with the consecrations who hoped to maintain both loyalty to the papacy and their attachment to traditional liturgical forms.

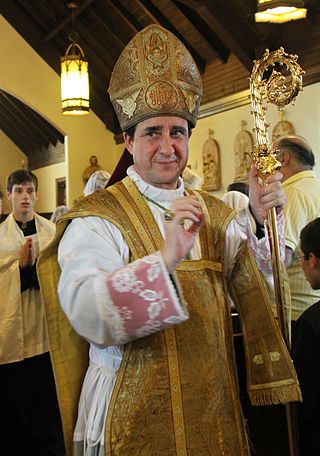

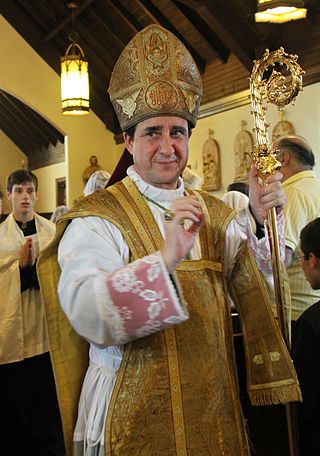

Alfonso de Galarreta Genua,, is a Spanish-born Argentine bishop of the Society of Saint Pius X. Bishop de Galarreta has served as the First Assistant of the Society of Saint Pius X, working under the direction of the Superior General Fr. Davide Pagliarani, since 2018. In addition to this, Bishop de Galaretta has been the President of the SSPX—Vatican Commission since 2009, which directs the Society's correspondence with the Holy See.

Doctor of Canon Law is the doctoral-level terminal degree in the studies of canon law of the Roman Catholic Church. It can also be an honorary degree awarded by Anglican colleges. It may also be abbreviated ICD or dr.iur.can., ICDr, DCL, DCnl, DDC, or DCanL. A doctor of both laws is a JUD or UJD.

The canon law of the Catholic Church is "how the Church organizes and governs herself". It is the system of laws and ecclesiastical legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities of the Catholic Church to regulate its external organization and government and to order and direct the activities of Catholics toward the mission of the Church. It was the first modern Western legal system and is the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the West, while the unique traditions of Eastern Catholic canon law govern the 23 Eastern Catholic particular churches sui iuris.

A formal act of defection from the Catholic Church was an externally provable juridic act of departure from the Catholic Church that existed between 1983 and 2010.

Regarding the canon law of the Catholic Church, canonists provide and obey rules for the interpretation and acceptation of words, in order that legislation is correctly understood and the extent of its obligation is determined.

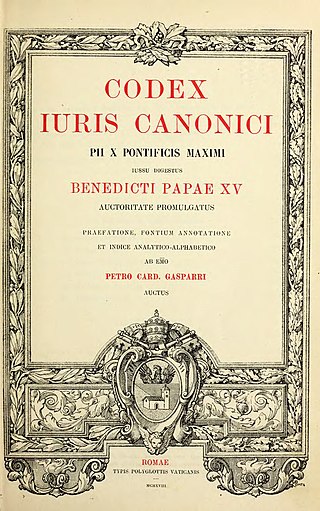

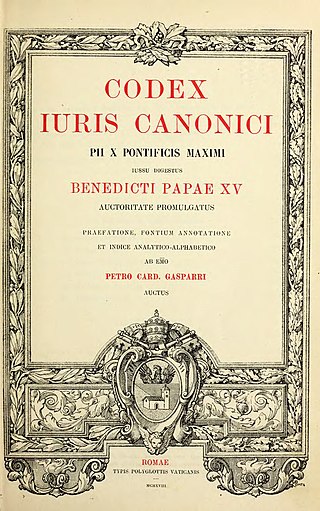

The 1917 Code of Canon Law, also referred to as the Pio-Benedictine Code, is the first official comprehensive codification of Latin canon law.

The 1983 Code of Canon Law, also called the Johanno-Pauline Code, is the "fundamental body of ecclesiastical laws for the Latin Church". It is the second and current comprehensive codification of canonical legislation for the Latin Church of the Catholic Church. The 1983 Code of Canon Law was promulgated on 25 January 1983 by John Paul II and took legal effect on the First Sunday of Advent 1983. It replaced the 1917 Code of Canon Law which had been promulgated by Benedict XV on 27 May 1917.

Communitas perfecta or societas perfecta is the Latin name given to one of several ecclesiological, canonical, and political theories of the Catholic Church. The doctrine teaches that the church is a self-sufficient or independent group which already has all the necessary resources and conditions to achieve its overall goal of the universal salvation of mankind. It has historically been used in order to define church–state relations and to provide a theoretical basis for the legislative powers of the church in the philosophy of Catholic canon law.

The canonical situation of the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX), a group founded in 1970 by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, is unresolved.

In the canon law of the Catholic Church, excommunication is a form of censure. In the formal sense of the term, excommunication includes being barred not only from the sacraments but also from the fellowship of Christian baptism. The principal and severest censure, excommunication presupposes guilt; and being the most serious penalty that the Catholic Church can inflict, it supposes a grave offense. The excommunicated person is considered by Catholic ecclesiastical authority as an exile from the Church, for a time at least.

A particular church is an ecclesiastical community of followers headed by a bishop, as defined by Catholic canon law and ecclesiology. A liturgical rite, a collection of liturgies descending from shared historic or regional context, depends on the particular church the bishop belongs to. Thus the term "particular church" refers to an institution, and "liturgical rite" to its ritual practices.

The Latin Church is the largest autonomous particular church within the Catholic Church, whose members constitute the vast majority of the 1.3 billion Christians in communion with the pope in Rome. The Latin Church is one of 24 churches sui iuris in communion with the pope; the other 23 are collectively referred to as the Eastern Catholic Churches, and have approximately 18 million members combined.

Treatise on Law is Thomas Aquinas' major work of legal philosophy. It forms questions 90–108 of the Prima Secundæ of the Summa Theologiæ, Aquinas' masterwork of Scholastic philosophical theology. Along with Aristotelianism, it forms the basis for the legal theory of Catholic canon law.

The term ratum sed non consummatum or ratum et non consummatum refers to a juridical-sacramental category of marriage in Catholic matrimonial canon law. If a matrimonial celebration takes place (ratification) but the spouses have not yet engaged in intercourse (consummation), then the marriage is said to be a marriage ratum sed non consummatum. The Tribunal of the Roman Rota has exclusive competence to dispense from marriages ratum sed non consummatum, which can only be granted for a "just reason". This process should not be confused with the process for declaring the nullity of marriage, which is treated of in a separate title of the 1983 Code of Canon Law.

A determinatio is an authoritative determination by the legislator concerning the application of practical principles, that is not necessitated by deduction from natural or divine law but is based on the contingencies of practical judgement within the possibilities allowed by reason. The concept derives from the legal philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, and continues to be a part of discussions in natural law theory.

The Eastern Catholic canon law is the law of the 23 Catholic sui juris (autonomous) particular churches of the Eastern Catholic tradition. Eastern Catholic canon law includes both the common tradition among all Eastern Catholic Churches, now chiefly contained in the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, as well as the particular law proper to each individual sui juris particular Eastern Catholic Church. Oriental canon law is distinguished from Latin canon law, which developed along a separate line in the remnants of the Western Roman Empire, and is now chiefly codified in the 1983 Code of Canon Law.