The Symmachian forgeries are a sheaf of forged documents produced in the curia of Pope Symmachus (498–514) in the beginning of the sixth century, in the same cycle that produced the Liber Pontificalis . [3] In the context of the conflict between partisans of Symmachus and Antipope Laurentius the purpose of these libelli was to further papal pretensions of the independence of the bishops of Rome from criticisms and judgment of any ecclesiastical tribunal, putting them above law clerical and secular by supplying spurious documents supposedly of an earlier age.

The Catholic Encyclopedia states: "During the dispute between Pope St. Symmachus and the anti-pope Laurentius, the adherents of Symmachus drew up four apocryphal writings called the 'Symmachian Forgeries'. [...] The object of these forgeries was to produce alleged instances from earlier times to support the whole procedure of the adherents of Symmachus, and, in particular, the position that the Roman bishop could not be judged by any court composed of other bishops." [4]

One of its modern editors, Louis Duchesne, divided those documents in two groups: a group produced in the heat of the conflict involving Symmachus, and a later group. Among writings to support Symmachus, Gesta de Xysti purgatione narrated a decision by Sixtus III, who cleared his name from defamation and permanently excommunicated the offender; Gesta de Polychronii episcopi Hierosolynitani accusatione concerned a purely apocryphal simonical Bishop of Jerusalem "Polychronius", who claimed Jerusalem as the first see and his supremacy over other bishops; Gesta Liberii papae concerned mass baptisms carried out by Pope Liberius during his exile from the seat of Peter; and Sinuessanae synodi gesta de Marcellino recounted the accusation brought against Pope Marcellinus, that in the company of the Emperor Diocletian he had offered incense to the pagan gods, making the point that when Marcellinus eventually confessed to the misdeed it was declared that the pope had condemned himself, since no one had ever judged the pontiff, because the first see will not be judged by anyone. [5]

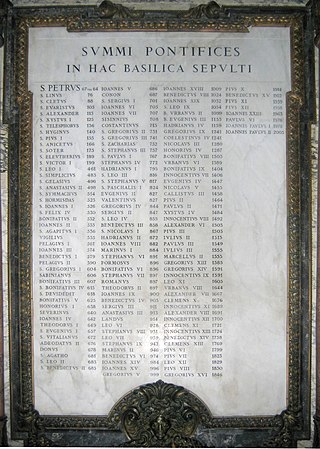

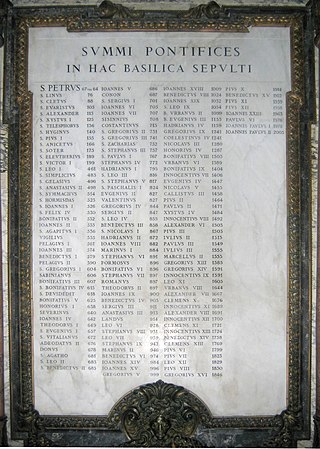

The Liber Pontificalis is a book of biographies of popes from Saint Peter until the 15th century. The original publication of the Liber Pontificalis stopped with Pope Adrian II (867–872) or Pope Stephen V (885–891), but it was later supplemented in a different style until Pope Eugene IV (1431–1447) and then Pope Pius II (1458–1464). Although quoted virtually uncritically from the 8th to 18th centuries, the Liber Pontificalis has undergone intense modern scholarly scrutiny. The work of the French priest Louis Duchesne, and of others has highlighted some of the underlying redactional motivations of different sections, though such interests are so disparate and varied as to render improbable one popularizer's claim that it is an "unofficial instrument of pontifical propaganda."

Pope Anastasius II was the bishop of Rome from 24 November 496 to his death. He was an important figure in trying to end the Acacian schism, but his efforts resulted in the Laurentian schism, which followed his death. Anastasius was born in Rome, the son of a priest, and is buried in St. Peter's Basilica.

Pope Damasus I, also known as Damasus of Rome, was the bishop of Rome from October 366 to his death. He presided over the Council of Rome of 382 that determined the canon or official list of sacred scripture. He spoke out against major heresies, thus solidifying the faith of the Catholic Church, and encouraged production of the Vulgate Bible with his support for Jerome. He helped reconcile the relations between the Church of Rome and the Church of Antioch, and encouraged the veneration of martyrs.

Pope Siricius was the bishop of Rome from December 384 to his death. In response to inquiries from Bishop Himerius of Tarragona, Siricius issued the Directa decretal, containing decrees of baptism, church discipline and other matters. His are the oldest completely preserved papal decretals. He is sometimes said to have been the first bishop of Rome to call himself pope.

Pope Sylvester I was the bishop of Rome from 31 January 314 until his death on 31 December 335. He filled the See of Rome at an important era in the history of the Western Church, though very little is known of his life.

Pope Zosimus was the bishop of Rome from 18 March 417 to his death on 26 December 418. He was born in Mesoraca, Calabria. Zosimus took a decided part in the protracted dispute in Gaul as to the jurisdiction of the See of Arles over that of Vienne, giving energetic decisions in favour of the former, but without settling the controversy. His fractious temper coloured all the controversies in which he took part, in Gaul, Africa and Italy, including Rome, where at his death the clergy were very much divided.

Pope Symmachus was the bishop of Rome from 22 November 498 to his death. His tenure was marked by a serious schism over who was elected pope by a majority of the Roman clergy.

Pope Hormisdas was the bishop of Rome from 20 July 514 to his death. His papacy was dominated by the Acacian schism, started in 484 by Acacius of Constantinople's efforts to placate the Monophysites. His efforts to resolve this schism were successful, and on 28 March 519, the reunion between Constantinople and Rome was ratified in the cathedral of Constantinople before a large crowd.

Pope John I was the bishop of Rome from 13 August 523 to his death. He was a native of Siena, in Italy. He was sent on a diplomatic mission to Constantinople by the Ostrogoth King Theoderic to negotiate better treatment for Arians. Although John was relatively successful, upon his return to Ravenna, Theoderic had him imprisoned for allegedly conspiring with Constantinople. The frail pope died of neglect and ill-treatment.

The Donation of Constantine is a forged Roman imperial decree by which the 4th-century emperor Constantine the Great supposedly transferred authority over Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the Pope. Composed probably in the 9th century, it was used, especially in the 13th century, in support of claims of political authority by the papacy.

Laurentius was the Archpriest of Santa Prassede and later antipope of the See of Rome. Elected in 498 at the Basilica Saint Mariae with the support of a dissenting faction with Byzantine sympathies, who were supported by Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius I Dicorus, in opposition to Pope Symmachus, the division between the two opposing factions split not only the church, but the Senate and the people of Rome. However, Laurentius remained in Rome as pope until 506.

The Diocese of Porto–Santa Rufina is a Latin suburbicarian diocese of the Diocese of Rome and a diocese of the Catholic Church in Italy. It was formed from the union of two dioceses. The diocese of Santa Rufina was also formerly known as Silva Candida.

Papal appointment was a medieval method of selecting the Pope. Popes have always been selected by a council of Church fathers; however, Papal selection before 1059 was often characterized by confirmation or nomination by secular European rulers or by the preceding pope. The later procedures of the Papal conclave are in large part designed to prohibit interference of secular rulers, which to some extent characterized the first millennium of the Roman Catholic Church, e. g. in practices such as the creation of crown-cardinals and the claimed but invalid jus exclusivae. Appointment may have taken several forms, with a variety of roles for the laity and civic leaders, Byzantine and Germanic emperors, and noble Roman families. The role of the election vis-a-vis the general population and the clergy was prone to vary considerably, with a nomination carrying weight that ranged from nearly determinative to merely suggestive, or as ratification of a concluded election.

The selection of the Pope, the Bishop of Rome and Supreme Pontiff of the Catholic Church, prior to the promulgation of In Nomine Domini in AD 1059 varied throughout history. Popes were often putatively appointed by their predecessors or by political rulers. While some kind of election often characterized the procedure, an election that included meaningful participation of the laity was rare, especially as the Popes' claims to temporal power solidified into the Papal States. The practice of papal appointment during this period would later result in the putative jus exclusivae, i.e., the claimed but invalid right to veto the selection that Catholic monarchs exercised into the twentieth century.

The Ostrogothic Papacy was a period from 493 to 537 where the papacy was strongly influenced by the Ostrogothic Kingdom, if the pope was not outright appointed by the Ostrogothic King. The selection and administration of popes during this period was strongly influenced by Theodoric the Great and his successors Athalaric and Theodahad. This period terminated with Justinian I's (re)conquest of Rome during the Gothic War (535–554), inaugurating the Byzantine Papacy (537–752).

Constantine the Great's (272–337) relationship with the four Bishops of Rome during his reign is an important component of the history of the Papacy, and more generally the history of the Catholic Church.

The Mausoleum of Helena is an ancient building in Rome, Italy, located on the Via Casilina, corresponding to the 3rd mile of the ancient Via Labicana. It was built by the Roman emperor Constantine I between 326 and 330, originally as a tomb for himself, but later assigned to his mother, Helena, who died in 330.

The pseudo-Council of Sinuessa was a purported gathering of bishops in 303 at Sinuessa, Italy, the purpose being a trial of Marcellinus on charges of apostasy. It is generally accepted that the gathering never took place and that the purported council documents were forged for political purposes in the 6th century during the schism between Symmachus and Laurentius, who both claimed the Holy See. The collection of forgeries, including the Council of Sinuessa, is collectively known as the Symmachian forgeries.

The Acts of Sylvester are a series of legendary tales about the fourth-century bishop of Rome, Sylvester I. Sylvester was the bishop of Rome at the critical point in European history when Constantine the Great became the first Christian emperor. Yet, despite the claims that arose in later centuries of Roman primacy, some academics question whether Sylvester played a significant role in the Christianization of the Roman Empire during this crucial period. They contend these legends arose in order to augment the reputation of Sylvester and to correct a number of embarrassing events for the Church, such as his conspicuous absence at both the Synod of Arles in 314 and the First Council of Nicaea in 325, and the fact that Constantine had been baptized by an Arian bishop.

The Constitutum Silvestri is one of five fictitious stories known collectively as the Symmachian forgeries, that arose between 501 and 502 at the time of the political battle for the papacy between Pope Symmachus (498-514) and antipope Laurentius.