The Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymously, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus. The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia. It refers to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures in Europe and Middle East, between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. In Europe it spans roughly 15,000 to 5,000 BP; in the Middle East roughly 20,000 to 10,000 BP. The term is less used of areas farther east, and not at all beyond Eurasia and North Africa.

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, honey, bird eggs, or anything safe to eat, and/or by hunting game. This is a common practice among most omnivores. Hunter-gatherer societies stand in contrast to the more sedentary agricultural societies, which rely mainly on cultivating crops and raising domesticated animals for food production, although the boundaries between the two ways of living are not completely distinct.

Ground sloths are a diverse group of extinct sloths in the mammalian superorder Xenarthra. Ground sloths varied widely in size, with the largest genera Megatherium and Eremotherium being around the size of elephants. Ground sloths are a paraphyletic group, as living tree sloths are thought to have evolved from ground sloth ancestors.

The term Negrito refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. Populations often described as Negrito include: the Andamanese peoples of the Andaman Islands, the Semang peoples of Peninsular Malaysia, the Maniq people of Southern Thailand, as well as the Aeta of Luzon, the Ati and Tumandok of Panay, the Mamanwa of Mindanao, and about 30 other officially recognized ethnic groups in the Philippines.

Africa has the longest record of human habitation in the world. The first hominins emerged 6-7 million years ago, and among the earliest anatomically modern human skulls found so far were discovered at Omo Kibish, Jebel Irhoud, and Florisbad.

The founder crops or primary domesticates are a group of flowering plants that were domesticated by early farming communities in Southwest Asia and went on to form the basis of agricultural economies across Eurasia. As originally defined by Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, they consisted of three cereals, four pulses, and flax. Subsequent research has indicated that many other species could be considered founder crops. These species were amongst the first domesticated plants in the world.

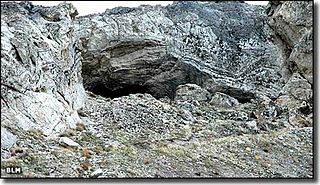

Fort Rock Cave was the site of the earliest evidence of human habitation in the US state of Oregon before the excavation of Paisley Caves. Fort Rock Cave featured numerous well-preserved sagebrush sandals, ranging from 9,000 to 13,000 years old. The cave is located approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of Fort Rock near Fort Rock State Natural Area in Lake County. Fort Rock Cave was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1961, and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Azykh Cave, also referred to as Azokh Cave, is a six-cave complex in Azerbaijan, known as a habitation site of prehistoric humans. It is situated near the village of Azykh in the Khojavend District.

Mumba Cave, located near the highly alkaline Lake Eyasi in Karatu District, Arusha Region, Tanzania. The cave is a rich archaeological site noted for deposits spanning the transition between the Middle Stone Age and Late Stone Age in Eastern Africa. The transitional nature of the site has been attributed to the large presence of its large assemblage of ostrich eggshell beads and more importantly, the abundance of microlith technology. Because these type artifacts were found within the site it has led archaeologists to believe that the site could provide insight into the origins of modern human behavior. The cave was originally tested by Ludwig Kohl-Larsen and his wife Margit in their 1934 to 1936 expedition. They found abundant artifacts, rock art, and burials. However, only brief descriptions of these findings were ever published. That being said, work of the Kohl-Larsens has been seen as very accomplished due to their attention to detail, especially when one considers that neither was versed in proper archaeological techniques at the time of excavation. The site has since been reexamined in an effort to reanalyze and complement the work that has already been done, but the ramifications of improper excavations of the past are still being felt today, specifically in the unreliable collection of C-14 data and confusing stratigraphy.

Cueva de la Candelaria is an archaeological site located the Mexican state of Coahuila. It is a cave that was used as cemetery by nomad visitors. Early site research was made in 1953 and there was a later season in 1954. As a result of these investigations, many materials were recovered and are kept by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH).

Huápoca is an archaeological site located 36 kilometers west of Ciudad Madera, in the Huápoca Canyon region, northwest of the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

Lovelock Cave (NV-Ch-18) is a North American archaeological site previously known as Sunset Guano Cave, Horseshoe Cave, and Loud Site 18. The cave is about 150 feet (46 m) long and 35 feet (11 m) wide. Lovelock Cave is one of the most important classic sites of the Great Basin region because the conditions of the cave are conducive to the preservation of organic and inorganic material. The cave was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 24, 1984. It was the first major cave in the Great Basin to be excavated, and the Lovelock Cave people are part of the University of California Archaeological Community's Lovelock Cave Station.

Franktown Cave is located 25 miles (40 km) south of Denver, Colorado on the north edge of the Palmer Divide. It is the largest rock shelter documented on the Palmer Divide, which contains artifacts from many prehistoric cultures. Prehistoric hunter-gatherers occupied Franktown Cave intermittently for 8,000 years beginning about 6400 BC The site held remarkable lithic and ceramic artifacts, but it is better known for its perishable artifacts, including animal hides, wood, fiber and corn. Material goods were produced for their comfort, task-simplification and religious celebration. There is evidence of the site being a campsite or dwelling as recently as AD 1725.

The Trinchera Cave Archeological District (5LA9555) is an archaeological site in Las Animas County, Colorado with artifacts primarily dating from 1000 BC to AD 1749, although there were some Archaic period artifacts found. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001 and is located on State Trust Lands.

The Basketmaker culture of the pre-Ancestral Puebloans began about 1500 BC and continued until about AD 750 with the beginning of the Pueblo I Era. The prehistoric American southwestern culture was named "Basketmaker" for the large number of baskets found at archaeological sites of 3,000 to 2,000 years ago.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the prehistoric people of Colorado, which covers the period of when Native Americans lived in Colorado prior to contact with the Domínguez–Escalante expedition in 1776. People's lifestyles included nomadic hunter-gathering, semi-permanent village dwelling, and residing in pueblos.

Elands Bay Cave is located near the mouth of the Verlorenvlei estuary on the Atlantic coast of South Africa's Western Cape Province. The climate has continuously become drier since the habitation of hunter-gatherers in the Later Pleistocene. The archaeological remains recovered from previous excavations at Elands Bay Cave have been studied to help answer questions regarding the relationship of people and their landscape, the role of climate change that could have determined or influenced subsistence changes, and the impact of pastoralism and agriculture on hunter-gatherer communities.

Njoro River Cave is an archaeological site on the Mau Escarpment, Kenya, that was first excavated in 1938 by Mary Leakey and her husband Louis Leakey. Excavations revealed a mass cremation site created by Elmenteitan pastoralists during the Pastoral Neolithic roughly 3350-3050 BP. Excavations also uncovered pottery, beads, stone bowls, basket work, pestles and flakes. The Leakeys' excavation was one of the earliest to uncover ancient beads and tools in the area and a later investigation in 1950 was the first to use radiocarbon dating in East Africa.

Boomplaas Cave is located in the Cango Valley in the foothills of the Swartberg mountain range, north of Oudtshoorn, Eden District Municipality in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. It has a 5 m (16 ft) deep stratified archaeological sequence of human presence, occupation and hunter-gatherer/herder acculturation that might date back as far as 80,000 years. The site's documentation contributed to the reconstruction of palaeo-environments in the context of changes in climate within periods of the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene. The cave has served multiple functions during its occupation, such as a kraal (enclosure) for animals, a place for the storage of oil rich fruits and as a hunting camp. Circular stone hearths and calcified dung remains of domesticated sheep as well as stone adzes and pottery art were excavated indicating that humans lived at the site and kept animals.