An alphabet is a standard set of letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters correspond to phonemes, the categories of sounds that can distinguish one word from another in a given language. Not all writing systems represent language in this way: a syllabary assigns symbols to spoken syllables, while logographies assign symbols to words, morphemes, or other semantic units.

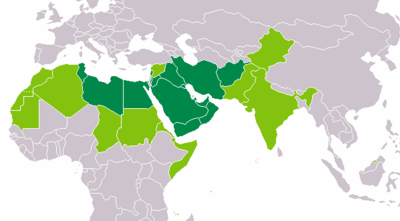

An abjad, also abgad, is a writing system in which only consonants are represented, leaving vowel sounds to be inferred by the reader. This contrasts with alphabets, which provide graphemes for both consonants and vowels. The term was introduced in 1990 by Peter T. Daniels. Other terms for the same concept include partial phonemic script, segmentally linear defective phonographic script, consonantary, consonant writing, and consonantal alphabet.

The Hebrew alphabet, known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is traditionally an abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew language and other Jewish languages, most notably Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic, and Judeo-Persian. In modern Hebrew, vowels are increasingly introduced. It is also used informally in Israel to write Levantine Arabic, especially among Druze. It is an offshoot of the Imperial Aramaic alphabet, which flourished during the Achaemenid Empire and which itself derives from the Phoenician alphabet.

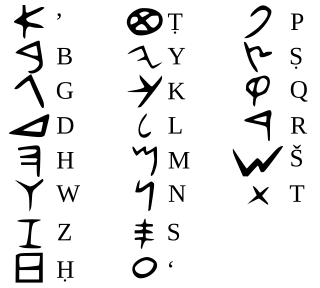

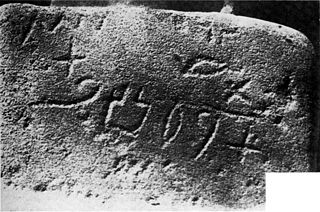

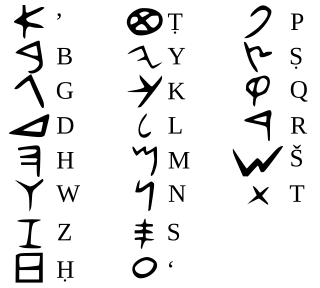

The Phoenician alphabet is a consonantal alphabet used across the Mediterranean civilization of Phoenicia for most the 1st millennium BC. It was the first mature alphabet, and attested in Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. In the history of writing systems, the Phoenician script also marked the first to have a fixed writing direction—while previous systems were multi-directional, Phoenecian was written horizontally, from right to left. Its developed directly from the Proto-Sinaitic script used during Late Bronze Age, which was derived in turn from Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The Ugaritic writing system is a Cuneiform Abjad with syllabic elements used from around either 1400 BCE or 1300 BCE for Ugaritic, an extinct Northwest Semitic language, and discovered in Ugarit, Syria, in 1928. It has 30 letters. Other languages were occasionally written in the Ugaritic script in the area around Ugarit, although not elsewhere.

Proto-Canaanite is the name given to

The Paleo-Hebrew script, also Palaeo-Hebrew, Proto-Hebrew or Old Hebrew, is the writing system found in inscriptions of Canaanite languages from the region of Southern Canaan, also known as biblical Israel and Judah. It is considered to be the script used to record the original texts of the Hebrew Bible due to its similarity to the Samaritan script, as the Talmud stated that the Hebrew ancient script was still used by the Samaritans. The Talmud described it as the "Libona'a script", translated by some as "Lebanon script". Use of the term "Paleo-Hebrew alphabet" is due to a 1954 suggestion by Solomon Birnbaum, who argued that "[t]o apply the term Phoenician [from Northern Canaan, today's Lebanon] to the script of the Hebrews [from Southern Canaan, today's Israel-Palestine] is hardly suitable". The Paleo-Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets are two slight regional variants of the same script.

Zayin is the seventh letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician zayn 𐤆, Hebrew zayīn ז, Aramaic zain 𐡆, Syriac zayn ܙ, and Arabic zāy ز. It represents the sound.

Heth, sometimes written Chet or Ḥet, is the eighth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ḥēt 𐤇, Hebrew ḥēt ח, Aramaic ḥēṯ 𐡇, Syriac ḥēṯ ܚ, and Arabic ḥāʾ ح.

Teth, also written as Ṭēth or Tet, is the ninth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ṭēt 𐤈, Hebrew ṭēt ט, Aramaic ṭēṯ 𐡈, Syriac ṭēṯ ܛ, and Arabic ṭāʾ ط. It is the 16th letter of the modern Arabic alphabet. The Persian ṭa is pronounced as a hard "t" sound and is the 19th letter in the modern Persian alphabet. The Phoenician letter also gave rise to the Greek theta (Θ), originally an aspirated voiceless dental stop but now used for the voiceless dental fricative. The Arabic letter (ط) is sometimes transliterated as Tah in English, for example in Arabic script in Unicode.

Ayin is the sixteenth letter of the Semitic scripts, including Phoenician ʿayin 𐤏, Hebrew ʿayin ע, Aramaic ʿē 𐡏, Syriac ʿē ܥ, and Arabic ʿayn ع.

He is the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician hē 𐤄, Hebrew hē ה, Aramaic hē 𐡄, Syriac hē ܗ, and Arabic hāʾ ه. Its sound value is the voiceless glottal fricative.

Aleph is the first letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ʾālep 𐤀, Hebrew ʾālef א, Aramaic ʾālap 𐡀, Syriac ʾālap̄ ܐ, Arabic ʾalif ا, and North Arabian 𐪑. It also appears as South Arabian 𐩱 and Ge'ez ʾälef አ.

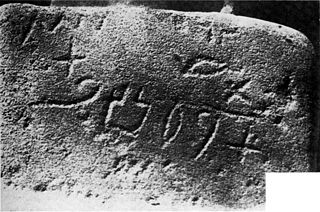

The Proto-Sinaitic script is a Middle Bronze Age writing system known from a small corpus of about 30-40 inscriptions and fragments from Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula, as well as two inscriptions from Wadi el-Hol in Middle Egypt. Together with about 20 known Proto-Canaanite inscriptions, it is also known as Early Alphabetic, i.e. the earliest trace of alphabetic writing and the common ancestor of both the Ancient South Arabian script and the Phoenician alphabet, which led to many modern alphabets including the Greek alphabet. According to common theory, Canaanites or Hyksos who spoke a Canaanite language repurposed Egyptian hieroglyphs to construct a different script.

Bet, Beth, Beh, or Vet is the second letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician bēt 𐤁, Hebrew bēt ב, Aramaic bēṯ 𐡁, Syriac bēṯ ܒ, and Arabic bāʾ ب. Its sound value is the voiced bilabial stop ⟨b⟩ or the voiced labiodental fricative ⟨v⟩.

A defective script is a writing system that does not represent all the phonemic distinctions of a language. This means that the concept is always relative to a given language. Taking the Latin alphabet used in Italian orthography as an example, the Italian language has seven vowels, but the alphabet has only five vowel letters to represent them; in general, the difference between the phonemes close and open is simply ignored, though stress marks, if used, may distinguish them. Among the Italian consonants, both and are written ⟨s⟩, and both and are written ⟨z⟩; stress and hiatus are also not reliably distinguished.

The Byblos script, also known as the Byblos syllabary, Pseudo-hieroglyphic script, Proto-Byblian, Proto-Byblic, or Byblic, is an undeciphered writing system, known from ten inscriptions found in Byblos, a coastal city in Lebanon. The inscriptions are engraved on bronze plates and spatulas, and carved in stone. They were excavated by Maurice Dunand, from 1928 to 1932, and published in 1945 in his monograph Byblia Grammata. The inscriptions are conventionally dated to the second millennium BC, probably between the 18th and 15th centuries BC.

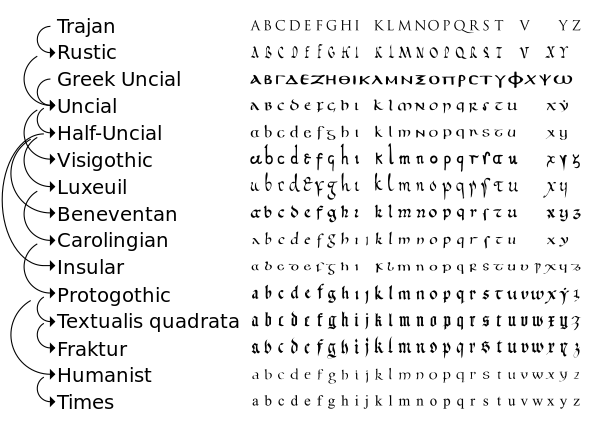

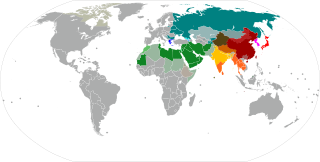

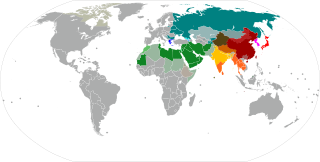

The Latin script is the most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world. It is the standard script of the English language and is often referred to simply as "the alphabet" in English. It is a true alphabet which originated in the 7th century BC in Italy and has changed continually over the last 2,500 years. It has roots in the Semitic alphabet and its offshoot alphabets, the Phoenician, Greek, and Etruscan. The phonetic values of some letters changed, some letters were lost and gained, and several writing styles ("hands") developed. Two such styles, the minuscule and majuscule hands, were combined into one script with alternate forms for the lower and upper case letters. Modern uppercase letters differ only slightly from their classical counterparts, and there are few regional variants.

A writing system comprises a particular set of symbols, called a script, as well as the rules by which the script represents a particular language. Writing systems can generally be classified according to how symbols function according to these rules, with the most common types being alphabets, syllabaries, and logographies. Alphabets use symbols called letters that correspond to spoken phonemes. Abjads generally only have letters for consonants, while pure alphabets have letters for both consonants and vowels. Abugidas use characters that correspond to consonant–vowel pairs. Syllabaries use symbols called syllabograms to represent syllables or moras. Logographies use characters that represent semantic units, such as words or morphemes.