Past contingent elections

1800 presidential election

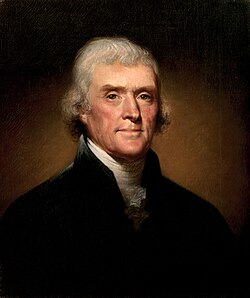

The 1800 presidential election pitted the Democratic-Republican ticket, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, against the Federalist Party ticket, John Adams and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Under the original process in the Constitution, each elector cast two votes with no distinction between those for president and those for vice president. The person receiving a majority of votes was elected president, and the person receiving the second highest number of votes was elected vice president. Each party planned to have one of their respective electors vote for a third candidate or abstain, so that their preferred presidential candidate (Adams for the Federalists and Jefferson for the Democratic-Republicans) would win one more vote than their other nominee. The Democratic-Republicans failed to execute their plan, however, resulting in a tie between Jefferson and Burr with 73 electoral votes each and a third-place finish for Adams with 65 votes. [9]

The Constitution mandates that, "if there be more than one who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately chuse [ sic ] by Ballot one of them for President." Therefore, Jefferson and Burr were admitted as candidates in the House election. Although the congressional election of 1800 turned majority control of the House of Representatives over to the Democratic-Republicans, the presidential election was decided by the outgoing House, which had a Federalist majority. [9] [10] Nonetheless, in contingent elections, the votes for the president are taken by states, with each delegation from each state having one vote; as a result, neither party had a majority in 1801, because some states had split delegations. Given the deadlock, Democratic-Republican representatives, who generally favored Jefferson for president, contemplated two distasteful possible outcomes: either the Federalists manage to engineer a victory for Burr, or they refuse to break the deadlock; the second scenario would leave a Federalist, Secretary of State John Marshall, as acting president come Inauguration Day. [11]

Over the course of seven days, from February 11 to 17, the House cast 35 successive ballots, with Jefferson receiving the votes of eight state delegations each time, one short of the necessary majority. On February 17, on the 36th ballot, Jefferson was elected after several Federalist representatives cast blank ballots, resulting in Maryland and Vermont's votes changing from no selection to Jefferson, thus giving him the votes of 10 states and the presidency. [9] [10] This situation was the impetus for the passage of the Twelfth Amendment, which provides for separate elections for president and vice president in the Electoral College. [9]

1824 presidential election

The 1824 presidential election came at the end of the Era of Good Feelings in American politics and had four Democratic-Republican candidates who won electoral votes: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay. While Andrew Jackson received more electoral and popular votes than any other candidate, he did not receive the majority of 131 electoral votes required to win the election, leading to a contingent election in the House of Representatives. Vice presidential candidate John C. Calhoun easily defeated his rivals, as the support of both the Adams and Jackson camps gave him an unassailable lead over the other candidates.

Following the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment, only the top three candidates in the electoral vote (Jackson, Adams, and Crawford) were admitted as candidates in the House: Clay, the Speaker of the House at the time, was eliminated. Clay subsequently threw his support to Adams, who was elected president on February 9, 1825, on the first ballot [12] [13] with 13 states, followed by Jackson with seven, and Crawford with four. Adams' victory shocked Jackson, who, as the winner of a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, expected to be elected president. By appointing Clay his Secretary of State, President Adams essentially declared him heir to the presidency, as Adams and his three predecessors had all served as Secretary of State. Jackson and his followers accused Adams and Clay of striking a "corrupt bargain", on which the Jacksonians would campaign for the next four years, ultimately attaining Jackson's victory in the Adams–Jackson rematch in the 1828 election.

1837 vice presidential election

In the 1836 presidential election, Democratic presidential candidate Martin Van Buren and his running mate Richard Mentor Johnson won the popular vote in enough states to receive a majority of the Electoral College. However, Virginia's 23 electors all became faithless electors and refused to vote for Johnson, leaving him one vote shy of the 148-vote majority required to elect him. Under the Twelfth Amendment, a contingent election in the Senate had to decide between Johnson and Whig candidate Francis Granger. Johnson was elected easily in a single ballot by 33 to 16. [14]