Mono Lake is a saline soda lake in Mono County, California, formed at least 760,000 years ago as a terminal lake in an endorheic basin. The lack of an outlet causes high levels of salts to accumulate in the lake which make its water alkaline.

Long Valley Caldera is a depression in eastern California that is adjacent to Mammoth Mountain. The valley is one of the Earth's largest calderas, measuring about 20 mi (32 km) long (east-west), 11 mi (18 km) wide (north-south), and up to 3,000 ft (910 m) deep.

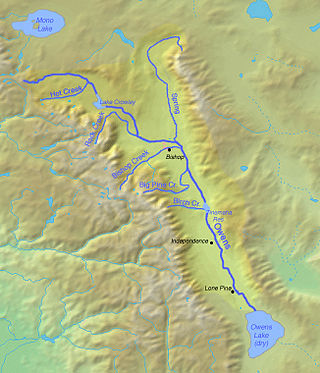

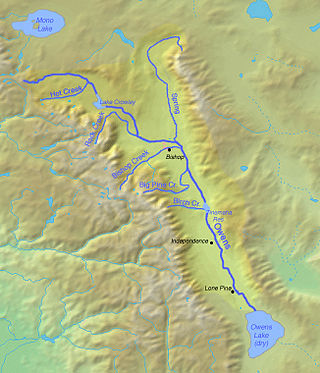

Inyo County is a county in the eastern central part of the U.S. state of California, located between the Sierra Nevada and the state of Nevada. In the 2020 census, the population was 19,016. The county seat is Independence. Inyo County is on the east side of the Sierra Nevada and southeast of Yosemite National Park in Central California. It contains the Owens River Valley; it is flanked to the west by the Sierra Nevada and to the east by the White Mountains and the Inyo Mountains. With an area of 10,192 square miles (26,400 km2), Inyo is the second-largest county by area in California, after San Bernardino County. Almost half of that area is within Death Valley National Park. However, with a population density of 1.8 people per square mile, it also has the second-lowest population density in California, after Alpine County.

Bishop is the most populous and only incorporated city in Inyo County, California, United States. It is located near the northern end of the Owens Valley within the Mojave Desert, at an elevation of 4,150 feet (1,260 m). The city was named after Bishop Creek, flowing out of the Sierra Nevada range; the creek was named after Samuel Addison Bishop, a settler in the Owens Valley. Bishop is a commercial and residential center, while many vacation destinations and tourist attractions in the Sierra Nevada are located nearby. The city covers approximately 1.9 square miles (4.9 km2), making it the county's largest community by land area.

Mount Whitney is the highest mountain in the contiguous United States, with an elevation of 14,505 feet (4,421 m). It is in East–Central California, in the Sierra Nevada, on the boundary between California's Inyo and Tulare counties, and 84.6 miles (136.2 km) west-northwest of North America's lowest topographic point, Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park, at 282 ft (86 m) below sea level. The mountain's west slope is in Sequoia National Park and the summit is the southern terminus of the John Muir Trail, which runs 211.9 mi (341.0 km) from Happy Isles in Yosemite Valley. The eastern slopes are in Inyo National Forest in Inyo County. Mount Whitney is ranked 18th by topographic isolation.

Owens Valley is an arid valley of the Owens River in eastern California in the United States. It is located to the east of the Sierra Nevada, west of the White Mountains and Inyo Mountains, and is split between the Great Basin Desert and the Mojave Desert. The mountain peaks on the West side reach above 14,000 feet (4,300 m) in elevation, while the floor of the Owens Valley is about 4,000 feet (1,200 m), making the valley the deepest in the United States. The Sierra Nevada casts the valley in a rain shadow, which makes Owens Valley "the Land of Little Rain". The bed of Owens Lake, now a predominantly dry endorheic alkali flat, sits on the southern end of the valley.

Owens Lake is a dry lake in the Owens Valley on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada in Inyo County, California. It is about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Lone Pine. Unlike most dry lakes in the Basin and Range Province that have been dry for thousands of years, Owens held significant water until 1913, when much of the Owens River was diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct, causing Owens Lake to desiccate by 1926. In 2006, 5% of the water flow was restored. As of 2013, it is the largest single source of dust pollution in the United States.

The Mono–Inyo Craters are a volcanic chain of craters, domes and lava flows in Mono County, Eastern California. The chain stretches 25 miles (40 km) from the northwest shore of Mono Lake to the south of Mammoth Mountain. The Mono Lake Volcanic Field forms the northernmost part of the chain and consists of two volcanic islands in the lake and one cinder cone volcano on its northwest shore. Most of the Mono Craters, which make up the bulk of the northern part of the Mono–Inyo chain, are phreatic volcanoes that have since been either plugged or over-topped by rhyolite domes and lava flows. The Inyo volcanic chain form much of the southern part of the chain and consist of phreatic explosion pits, and rhyolitic lava flows and domes. The southernmost part of the chain consists of fumaroles and explosion pits on Mammoth Mountain and a set of cinder cones south of the mountain; the latter are called the Red Cones.

The California Water Wars were a series of political conflicts between the city of Los Angeles and farmers and ranchers in the Owens Valley of Eastern California over water rights.

The Los Angeles Aqueduct system, comprising the Los Angeles Aqueduct and the Second Los Angeles Aqueduct, is a water conveyance system, built and operated by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. The Owens Valley aqueduct was designed and built by the city's water department, at the time named The Bureau of Los Angeles Aqueduct, under the supervision of the department's Chief Engineer William Mulholland. The system delivers water from the Owens River in the eastern Sierra Nevada mountains to Los Angeles.

The Truckee River is a river in the U.S. states of California and Nevada. The river flows northeasterly and is 121 miles (195 km) long. The Truckee is the sole outlet of Lake Tahoe and drains part of the high Sierra Nevada, emptying into Pyramid Lake in the Great Basin. Its waters are an important source of irrigation along its valley and adjacent valleys.

The Walker River is a river in west-central Nevada in the United States, approximately 62 miles (100 km) long. Fed principally by snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada of California, it drains an arid portion of the Great Basin southeast of Reno and flows into the endorheic basin of Walker Lake. The river is an important source of water for irrigation in its course through Nevada; water diversions have reduced its flow such that the level of Walker Lake has fallen 160 feet (49 m) between 1882 and 2010. The river was named for explorer Joseph Reddeford Walker, a mountain man and experienced scout who is known for establishing a segment of the California Trail.

Inyo National Forest is a United States National Forest covering parts of the eastern Sierra Nevada of California and the White Mountains of California and Nevada. The forest hosts several superlatives, including Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States; Boundary Peak, the highest point in Nevada; and the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, which protects the oldest living trees in the world. The forest, encompassing much of the Owens Valley, was established by Theodore Roosevelt as a way of sectioning off land to accommodate the Los Angeles Aqueduct project in 1907, making the Inyo National Forest one of the least wooded forests in the U.S. National Forest system.

Manzanar was a town in Inyo County, California, founded by water engineer and land developer George Chaffey. Most notably, Manzanar is known for its role in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The Mono Basin is an endorheic drainage basin located east of Yosemite National Park in California and Nevada. It is bordered to the west by the Sierra Nevada, to the east by the Cowtrack Mountains, to the north by the Bodie Hills, and to the south by the north ridge of the Long Valley Caldera.

Bishop Creek is a 10.1-mile-long (16.3 km) stream in Inyo County, California. It is the largest tributary of the Owens River. It has five hydroelectric plants owned by Southern California Edison, Bishop Creek #2–6. Bishop Creek #1 was never completed. Parts of the creek run through pipelines, or penstocks, to increase output at the power plants.

Hot Creek, starting as Mammoth Creek, is a stream in Mono County of eastern California, in the Western United States. It is within the Inyo National Forest.

Rush Creek is a 27.2-mile-long (43.8 km) creek in California on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, running east and then northeast to Mono Lake. Rush Creek is the largest stream in the Mono Basin, carrying 41% of the total runoff. It was extensively diverted by the Los Angeles Aqueduct system in the twentieth century until California Trout, Inc., the National Audubon Society, and the Mono Lake Committee sued Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) for continuous low flows in Rush Creek to maintain trout populations in good condition, which was ordered by the court in 1985.

The Paiute-Shoshone Indians of the Lone Pine Community of the Lone Pine Reservation is a federally recognized tribe of Mono and Timbisha Native American Indians near Lone Pine in Inyo County, California. They are related to the Owens Valley Paiute.

The Owens River course includes headwaters points near the Upper San Joaquin Watershed, reservoirs and diversion points, and the river's mouth at Owens Lake. The river drains the Crowley Lake Watershed of 1,900 sq mi (4,900 km2) and the north portion of the Owens Lake Watershed of 1,340 sq mi (3,500 km2).