Further reading

M40 Bantu Linguistic Varieties and Ethnolinguistic Groups (Bibliography)

Narrow Bantu languages (Zones A–S) (by Guthrie classification) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | This Bantu language-related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

| Sabi | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Eastern Zambia, Southeast DR-Congo |

| Linguistic classification | Niger–Congo? |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | bwil1246 (Bwile–Sabi)sabi1248 (Sabi) |

The Sabi languages are a group of Bantu languages established by Christine Ahmed. [1] They constitute much of Guthrie's Zone M. The languages, or clusters, along with their Guthrie identifications, are:

Bwile may belong here as well, as it is part of Guthrie's M40 group and Nurse (2003) does not note it as an exception, but it is not close to other languages and was not addressed by Ahmed. Similarly, although Spier (2020) focuses specifically on Aushi and includes an appendix comparing Sabi linguistic varieties, Bwile remains unaddressed due to limited available data. [2]

Nurse and Philippson [3] suspect that the Botatwe languages may be related.

M40 Bantu Linguistic Varieties and Ethnolinguistic Groups (Bibliography)

Kirundi, also known as Rundi, is a Bantu language and the national language of Burundi. It is a dialect of Rwanda-Rundi dialect continuum that is also spoken in Rwanda and adjacent parts of Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, as well as in Kenya. Kirundi is mutually intelligible with Kinyarwanda, the national language of Rwanda, and the two form parts of the wider dialect continuum known as Rwanda-Rundi.

Central Kilimanjaro, or Central Chaga, is a Bantu language of Tanzania spoken by the Chaga people.

Myene is a cluster of closely related Bantu varieties spoken in Gabon by about 46,000 people. It is perhaps the most divergent of the Narrow Bantu languages, though Nurse & Philippson (2003) place it in with the Tsogo languages (B.30). The more distinctive varieties are Mpongwe (Pongoué), Galwa (Galloa), and Nkomi.

Digo (Chidigo) is a Bantu language spoken primarily along the East African coast between Mombasa and Tanga by the Digo people of Kenya and Tanzania. The ethnic Digo population has been estimated at around 360,000, the majority of whom are presumably speakers of the language. All adult speakers of Digo are bilingual in Swahili, East Africa's lingua franca. The two languages are closely related, and Digo also has much vocabulary borrowed from neighbouring Swahili dialects.

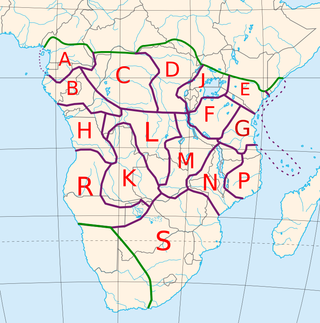

The 250 or so "Narrow Bantu languages" are conventionally divided up into geographic zones first proposed by Malcolm Guthrie (1967–1971). These were assigned letters A–S and divided into decades ; individual languages were assigned unit numbers, and dialects further subdivided. This coding system has become the standard for identifying Bantu languages; it was a practical way to distinguish many ambiguously named languages before the introduction of ISO 639-3 coding, and it continues to be widely used. Only Guthrie's Zone S is (sometimes) considered to be a genealogical group. Since Guthrie's time a Zone J has been set up as another possible genealogical group bordering the Great Lakes.

The Shona languages are a clade of Bantu languages coded Zone S.10 in Guthrie's classification. According to Nurse & Philippson (2003), the languages form a valid node. They are:

Sumbwa is an Eastern Bantu language, classified as F.23 by Malcolm Guthrie (1948). According to this classification, the language is assumed to be related to Kinyamwezi, Kisukuma, Kinilamba, Kirimi and other languages of Zone F (Guthrie 1948; 1967-71, although Nurse and Philippson 1980 and Maselle suggested that the language has had much influence from neighbouring languages. Quick inspection of the vocabulary shows that Sisumbwa appears to be closer to Nyamwezi than to any other language in the group. In terms of contacts, Sisumbwa speakers say that for a long time they have been in contact with speakers of Kisubi, Kirongo and Kizinza and Kiha, in addition to Kinyamwezi and Kisukuma.

Jita is a Bantu language of Tanzania, spoken on the southeastern shore of Lake Victoria/Nyanza and on the island of Ukerewe.

The Boma–Dzing languages are a clade of Bantu languages coded Zone B.80 in Guthrie's classification. According to Nurse & Philippson (2003), some of Guthrie's B.80 are related to the Teke languages (B.70), and some Yansi varieties belong with the Yaka languages (H.30), but the rest form a valid node. They are:

The Yaka languages are a clade of Bantu languages coded Zone H.30 in Guthrie's classification. According to Nurse & Philippson (2003), with a couple additions the languages form a valid node. They are:

The Lega–Binja languages are part of the Bantu languages coded Zone D.20 in Guthrie's classification, specifically D.24–26, which according to Nurse & Philippson (2003) form a valid clade. According to Ethnologue, Bembe, which Nurse & Philippson were not sure belonged in its traditional group of D.50, is the closest language to Lega-Mwenga; Glottolog has it closest to Songoora. The resulting languages are:

The Komo–Bira languages are part of the Bantu languages coded Zone D.20–30 in Guthrie's classification, specifically D.21, D.22, D.23, D.31, D.32. According to Nurse & Philippson (2003), they form a valid node; the rest of D.20 include the Lega–Holoholo languages, while the rest of the D.30 languages are not related to each other, apart from a close Budu–Ndaka group.

Tongwe (Sitongwe) and Bende (Sibende) constitute a clade of Bantu languages coded Zone F.10 in Guthrie's classification. According to Nurse & Philippson (2003), they form a valid node. Indeed, at 90% lexical similarity they may be dialects of a single language.

Kuba is a Bantu language of Kasai, Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Buja–Ngombe languages are a group of Bantu languages reported to be a valid clade by Nurse & Philippson (2003). They are Buja (C.37), the Ngombe languages (C.41), and Tembo (C.46):

Kinga is a Bantu language of the Kinga tribe in Tanzania. It is closely related to Magoma, but mutual intelligibility is low.

Bango, is a Bantu language spoken in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ethnologue suggests it may be a dialect of Budza, but Nurse & Philippson (2003) list it as one of the Bwa languages.

Kwakum is classified as belonging to the Bantu subgroup A90 (Kaka) of the Zone “A” Bantu languages, and specifically labelled A91 by Guthrie. According to one of the newest updates to the Bantu classification system, other languages belonging to this subgroup are: Pol (A92a), Pɔmɔ (A92b), Kweso (A92C) and Kakɔ (A93). The Kwakum people refer to themselves as either Kwakum or Bakoum. However, they say that the "Bakoum" pronunciation only began after the arrival of Europeans in Cameroon, though it is frequently used today. Kwakum is mainly spoken in the East region of Cameroon, southwest of the city Bertoua.

Aushi, known by native speakers as Ikyaushi, is a Bantu language primarily spoken in the Lwapula Province of Zambia and the (Haut-)Katanga Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Although many scholars argue that it is a dialect of the closely related Bemba, native speakers insist that it is a distinct language. Nonetheless, speakers of both linguistic varieties enjoy extensive mutual intelligibility, particularly in the Lwapula Province.

Proto-Bantu is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Bantu languages, a subgroup of the Southern Bantoid languages. It is thought to have originally been spoken in West/Central Africa in the area of what is now Cameroon. About 6,000 years ago, it split off from Proto-Southern Bantoid when the Bantu expansion began to the south and east. Two theories have been put forward about the way the languages expanded: one is that the Bantu-speaking people moved first to the Congo region and then a branch split off and moved to East Africa; the other is that the two groups split from the beginning, one moving to the Congo region, and the other to East Africa.