Zulu, or isiZulu as an endonym, is a Southern Bantu language of the Nguni branch spoken in Southern Africa. It is the language of the Zulu people, with about 12 million native speakers, who primarily inhabit the province of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. Zulu is the most widely spoken home language in South Africa, and it is understood by over 50% of its population. It became one of South Africa's 12 official languages in 1994.

Ganda or Luganda is a Bantu language spoken in the African Great Lakes region. It is one of the major languages in Uganda and is spoken by more than 5.56 million Baganda and other people principally in central Uganda, including the capital Kampala of Uganda. Typologically, it is an agglutinative, tonal language with subject–verb–object word order and nominative–accusative morphosyntactic alignment.

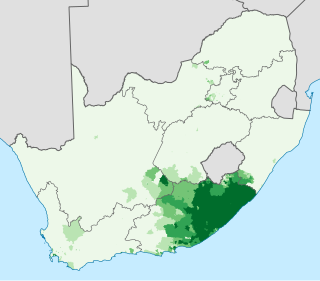

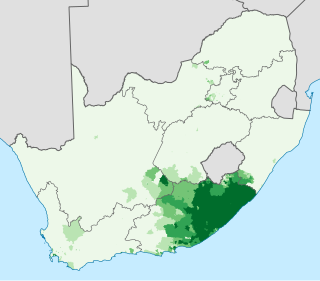

Xhosa, formerly spelled Xosa and also known by its local name isiXhosa, is a Nguni language and one of the official languages of South Africa and Zimbabwe. Xhosa is spoken as a first language by approximately 10 million people and as a second language by another 10 million, mostly in South Africa, particularly in Eastern Cape, Western Cape, Northern Cape and Gauteng, and also in parts of Zimbabwe and Lesotho. It has perhaps the heaviest functional load of click consonants in a Bantu language, with one count finding that 10% of basic vocabulary items contained a click.

Iñupiaq or Inupiaq, also known as Iñupiat, Inupiat, Iñupiatun or Alaskan Inuit, is an Inuit language, or perhaps group of languages, spoken by the Iñupiat people in northern and northwestern Alaska, as well as a small adjacent part of the Northwest Territories of Canada. The Iñupiat language is a member of the Inuit-Yupik-Unangan language family, and is closely related and, to varying degrees, mutually intelligible with other Inuit languages of Canada and Greenland. There are roughly 2,000 speakers. Iñupiaq is considered to be a threatened language, with most speakers at or above the age of 40. Iñupiaq is an official language of the State of Alaska, along with several other indigenous languages.

The Muscogee language, previously referred to by its exonym, Creek, is a Muskogean language spoken by Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole people, primarily in the US states of Oklahoma and Florida. Along with Mikasuki, when it is spoken by the Seminole, it is known as Seminole.

Supyire, or Suppire, is a Senufo language spoken in the Sikasso Region of southeastern Mali and in adjoining regions of Ivory Coast. In their native language, the noun sùpyìré means both "the people" and "the language spoken by the people".

Maasai or Maa is an Eastern Nilotic language spoken in Southern Kenya and Northern Tanzania by the Maasai people, numbering about 1.5 million. It is closely related to the other Maa varieties: Samburu, the language of the Samburu people of central Kenya, Chamus, spoken south and southeast of Lake Baringo ; and Parakuyu of Tanzania. The Maasai, Samburu, il-Chamus and Parakuyu peoples are historically related and all refer to their language as ɔl Maa. Properly speaking, "Maa" refers to the language and the culture and "Maasai" refers to the people "who speak Maa".

Northern Qiang is a Sino-Tibetan language of the Qiangic branch, more specifically falling under the Tibeto-Burman family. It is spoken by approximately 60,000 people in East Tibet, and in north-central Sichuan Province, China.

Dulong or Drung, Derung, Rawang, or Trung, is a Sino-Tibetan language in China. Dulong is closely related to the Rawang language of Myanmar (Burma). Although almost all ethnic Derung people speak the language to some degree, most are multilingual, also speaking Burmese, Lisu, and Mandarin Chinese except for a few very elderly people.

The phonology of Sesotho and those of the other Sotho–Tswana languages are radically different from those of "older" or more "stereotypical" Bantu languages. Modern Sesotho in particular has very mixed origins inheriting many words and idioms from non-Sotho–Tswana languages.

East Cree, also known as James Bay (Eastern) Cree, and East Main Cree, is a group of Cree dialects spoken in Quebec, Canada on the east coast of lower Hudson Bay and James Bay, and inland southeastward from James Bay. Cree is one of the most spoken non-official aboriginal languages of Canada. Four dialects have been tentatively identified including the Southern Inland dialect (Iyiniw-Ayamiwin) spoken in Mistissini, Oujé-Bougoumou, Waswanipi, and Nemaska; the Southern Coastal dialect (Iyiyiw-Ayamiwin) spoken in Nemaska, Waskaganish, and Eastmain; the Northern Coastal Dialects (Iyiyiw-Ayimiwin), one spoken in Wemindji and Chisasibi and the other spoken in Whapmagoostui. The dialects are mutually intelligible, though difficulty arises as the distance between communities increases.

Maliseet-Passamaquoddy is an endangered Algonquian language spoken by the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy peoples along both sides of the border between Maine in the United States and New Brunswick, Canada. The language consists of two major dialects: Maliseet, which is mainly spoken in the Saint John River Valley in New Brunswick; and Passamaquoddy, spoken mostly in the St. Croix River Valley of eastern Maine. However, the two dialects differ only slightly, mainly in their phonology. The indigenous people widely spoke Maliseet-Passamaquoddy in these areas until around the post-World War II era when changes in the education system and increased marriage outside of the speech community caused a large decrease in the number of children who learned or regularly used the language. As a result, in both Canada and the U.S. today, there are only 600 speakers of both dialects, and most speakers are older adults. Although the majority of younger people cannot speak the language, there is growing interest in teaching the language in community classes and in some schools.

Moro is a Kordofanian language spoken in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan, Sudan. It is part of the Western group of West Central Heiban Kordofonian languages and belongs to the Niger-Congo phylum. In 1982 there were an estimated 30,000 Moro-speakers. This was before the second Sudan civil war and therefore the recent number of speakers might differ. There can be noted an influence of Arabic and it is suspected that today approximately a fourth of all Moro vocabulary has a relation or an origin in the Arabic language.

Zulu grammar is the way in which meanings are encoded into wordings in the Zulu language. Zulu grammar is typical for Bantu languages, bearing all the hallmarks of this language family. These include agglutinativity, a rich array of noun classes, extensive inflection for person, tense and aspect, and a subject–verb–object word order.

Maybrat is a Papuan language spoken in the central parts of the Bird's Head Peninsula in the Indonesian province of Southwest Papua.

Pech or Pesh is a Chibchan language spoken in Honduras. It was formerly known as Paya, and continues to be referred to in this manner by several sources, though there are negative connotations associated with this term. Alternatively, it has rarely also been referred to as Seco, Bayano, Taia, Towka, and Poyuai. According to Ethnologue there were a thousand speakers in 1993. It is spoken near the north-central coast of Honduras, in the Dulce Nombre de Culmí municipality of Olancho Department.

The Otoro language classifies in to the Haiban Language family which belongs to the Kordofanian Languages and therefore it is a part of the Niger-Congo Languages. In a smaller view the Otoro is a segment of the „central branch “ from the so-called Koalib-Moro Groupe of the Languages which are spoken in the Nuba Mountains. The Otoro language is spoken within the geographical regions encompassing Kuartal, Zayd and Kauda in Sudan. The precise number of Otoro speakers is unknown, though current evaluates suggest it to be exceeding 15000 individuals.

Mungbam is a Southern Bantoid language of the Lower Fungom region of Cameroon. It is traditionally classified as a Western Beboid language, but the language family is disputed. Good et al. uses a more accurate name, the 'Yemne-Kimbi group,' but proposes the term 'Beboid.'

Ruuli is the Bantu language spoken by the Baruuli and Banyala people of Uganda primarily in Nakasongola and Kayunga districts. It is closely to the Nyoro language

Matlatzinca, or more specifically San Francisco Matlatzinca, is an endangered Oto-Manguean language of Western Central Mexico. The name of the language in the language itself is pjiekak'joo. The term "Matlatzinca" comes from the town's name in Nahuatl, meaning "the lords of the network." At one point, the Matlatzinca groups were called "pirindas," meaning "those in the middle."