The St. Lawrence River is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a roughly northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting the North American Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean, and forming the primary drainage outflow of the Great Lakes Basin. The river traverses the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec, as well as the U.S. state of New York, and demarcates part of the international boundary between Canada and the United States. It also provides the foundation for the commercial St. Lawrence Seaway.

The Gulf of St. Lawrence is the outlet of the North American Great Lakes via the St. Lawrence River into the Atlantic Ocean. The gulf is a semi-enclosed sea, covering an area of about 226,000 square kilometres (87,000 sq mi) and containing about 34,500 cubic kilometres (8,300 cu mi) of water, at an average depth of 152 metres (500 ft).

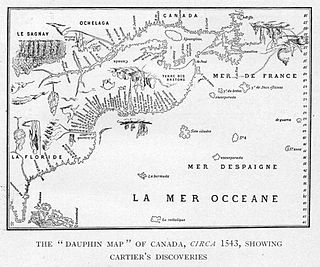

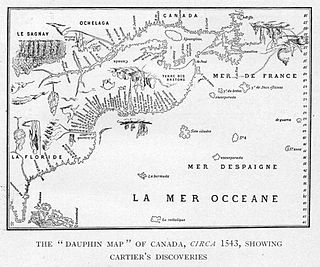

Jacques Cartier was a French-Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, which he named "The Country of Canadas" after the Iroquoian names for the two big settlements he saw at Stadacona and at Hochelaga.

Cabot Strait is a strait in eastern Canada approximately 110 kilometres wide between Cape Ray, Newfoundland and Cape North, Cape Breton Island. It is the widest of the three outlets for the Gulf of Saint Lawrence into the Atlantic Ocean, the others being the Strait of Belle Isle and Strait of Canso. It is named for the Italian explorer Giovanni Caboto.

This section of the Timeline of Quebec history concerns events through 1533.

Tadoussac is a village in Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers. The indigenous Innu call the place Totouskak meaning "bosom", probably in reference to the two round and sandy hills located on the west side of the village. According to other interpretations, it could also mean "place of lobsters", or "place where the ice is broken". Although located in Innu territory, the post was also frequented by the Mi'kmaq people in the second half of the 16th century, who called it Gtatosag. Alternate spellings of Tadoussac over the centuries included Tadousac, Tadoussak, and Thadoyzeau (1550). Tadoussac was first visited by Europeans in 1535 and was established in 1599 when the first trading post in Canada was formed there, in addition to a permanent settlement being placed in the same area that the Grand Hotel is located today.

Stadacona was a 16th-century St. Lawrence Iroquoian village not far from where Quebec City was founded in 1608.

While a variety of theories have been postulated for the name of Canada, its origin is now accepted as coming from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word kanata, meaning 'village' or 'settlement'. In 1535, indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Quebec City region used the word to direct French explorer Jacques Cartier to the village of Stadacona. Cartier later used the word Canada to refer not only to that particular village but to the entire area subject to Donnacona ; by 1545, European books and maps had begun referring to this small region along the Saint Lawrence River as Canada.

The Kingdom of Saguenay was a mythical kingdom that French-Breton maritime explorer Jacques Cartier tried to reach in 1535, supposedly located inland of present-day Quebec, Canada. The indigenous people had told Cartier about a rich kingdom and Cartier was given two ships by the French government to explore countries beyond Newfoundland. In 1542 Cartier founded the Charlesbourg-Royal settlement and his crew initially thought they had found large amounts of diamonds and gold in the area. The treasures were shipped back to France, but turned out to be quartz crystals and iron pyrites.

Hochelaga was a St. Lawrence Iroquois 16th century fortified village on or near Mount Royal in present-day Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Jacques Cartier arrived by boat on October 2, 1535; he visited the village on the following day. He was greeted well by the Iroquois, and named the mountain he saw nearby Mount Royal. Several names in and around Montreal and the Hochelaga Archipelago can be traced back to him.

Fort Charlesbourg Royal (1541—1543) is a National Historic Site in the Cap-Rouge neighbourhood of Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. Established by Jacques Cartier in 1541, it was France's first attempt at a colony in North America, and was abandoned two years later. In 1608, France would establish a successful colony, the Habitation de Québec, 15 kilometers east of the Cap-Rouge fort.

Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval, also named "l'élu de Poix" or the Sieur de Roberval, was a French officer who was appointed viceroy of Canada by Francis I. He led the first French colonial attempt in the Saint Laurent valley in the first half of the 16th century with the explorer Jacques Cartier.

This is a chronology and timeline of the colonization of North America, with founding dates of selected European settlements. See also European colonization of the Americas.

Laurentian, or St. Lawrence Iroquoian, was an Iroquoian language spoken until the late 16th century along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River in present-day Quebec and Ontario, Canada. It is believed to have disappeared with the extinction of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, likely as a result of warfare by the more powerful Mohawk from the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy to the south, in present-day New York state of the United States.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians were an Iroquoian Indigenous people who existed from the 14th century to about 1580. They concentrated along the shores of the St. Lawrence River in present-day Quebec and Ontario, Canada, and in the American states of New York and northernmost Vermont. They spoke Laurentian languages, a branch of the Iroquoian family.

The Basques were among the first people to catch whales commercially rather than purely for subsistence and dominated the trade for five centuries, spreading to the far corners of the North Atlantic and even reaching the South Atlantic. The French explorer Samuel de Champlain, when writing about Basque whaling in Terranova, described them as "the cleverest men at this fishing". By the early 17th century, other nations entered the trade in earnest, seeking the Basques as tutors, "for [they] were then the only people who understand whaling", lamented the English explorer Jonas Poole.

Basque Canadians are Canadian citizens of Basque descent, or Basque people who were born in the Basque Country and reside in Canada. As of 2021, 7,745 people claimed Basque ancestry.

Selma Barkham,, was a Canadian historian and geographer of international standing in the fields of the maritime history of Canada and of the Basque Country.

The Petit lac Jacques-Cartier is a freshwater body that flows into the rivière Jacques-Cartier Sud, in the unorganized territory of Lac-Jacques-Cartier, in the La Côte-de-Beaupré Regional County Municipality, in the administrative region of Capitale-Nationale, in province from Quebec, in Canada.

The settlement of Basques in the Americas was the process of Basque emigration and settlement in the New World. Thus, there is a deep cultural and social Basque heritage in some places in the Americas, the most famous of which being Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Central America, Guatemala and Antioquia, Colombia.