California Proposition 19 (also known as the Regulate, Control & Tax Cannabis Act) was a ballot initiative on the November 2, 2010 statewide ballot. It was defeated, with 53.5% of California voters voting "No" and 46.5% voting "Yes." [1] If passed, it would have legalized various marijuana-related activities, allowed local governments to regulate these activities, permitted local governments to impose and collect marijuana-related fees and taxes, and authorized various criminal and civil penalties. [2] In March 2010, it qualified to be on the November statewide ballot. [3] The proposition required a simple majority in order to pass, and would have taken effect the day after the election. [4] Yes on 19 was the official advocacy group for the initiative and California Public Safety Institute: No On Proposition 19 was the official opposition group. [5]

Cannabis, also known as marijuana among other names, is a psychoactive drug from the Cannabis plant used for medical or recreational purposes. The main psychoactive part of cannabis is tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), one of 483 known compounds in the plant, including at least 65 other cannabinoids. Cannabis can be used by smoking, vaporizing, within food, or as an extract.

A civil penalty or civil fine is a financial penalty imposed by a government agency as restitution for wrongdoing. The wrongdoing is typically defined by a codification of legislation, regulations, and decrees. The civil fine is not considered to be a criminal punishment, because it is primarily sought in order to compensate the state for harm done to it, rather than to punish the wrongful conduct. As such, a civil penalty, in itself, will not carry jail time or other legal penalties. For example, if a person were to dump toxic waste in a state park, the state would have the same right to seek to recover the cost of cleaning up the mess as would a private landowner, and to bring the complaint to a court of law, if necessary.

A majority is the greater part, or more than half, of the total. It is a subset of a set consisting of more than half of the set's elements.

Contents

- Effects of the bill

- Legalization of personal cannabis-related activities

- Local government regulation of commercial production and sale

- Other permissions

- Maintenance and addition of criminal and civil penalties

- Fiscal impact

- Arguments

- Support

- Opposition

- History

- Stance on initiative

- Support 2

- Opposition 2

- Polling history

- Polling differences by poll type

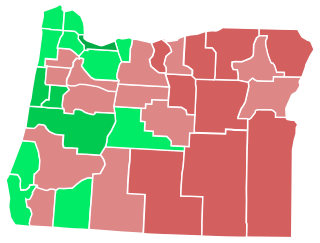

- Outcome

- Results by major county

- See also

- References

- External links

A similar initiative, "The Tax, Regulate, and Control Cannabis Act of 2010" (California Cannabis Initiative, CCI) was filed first and received by the Attorney General's Office July 15, 2010 assigned 09-0022 that would have legalized cannabis for adults 21 and older and included provisions to decriminalize industrial hemp, retroactive expunging of criminal records and release of non violent cannabis prisoners. A highly successful grassroots petition drive (CCI) was subsequently overwhelmed by the Taxcannabis2010 groups big budget and paid signature gatherers. Here is the LAO Summary of the Initiative that was defeated by the special interests that ultimately succeeded to put their version on the ballot as "Prop 19" with a subtly different Title: The Regulate, Control & Tax Cannabis Act. Many of the same group of special interests are supporting the 2016 Adult Use of Marijuana Act (AUMA).

Supporters of Proposition 19 argued that it would help with California's budget shortfall, would cut off a source of funding to violent drug cartels, and would redirect law enforcement resources to more dangerous crimes, [6] while opponents claimed that it contains gaps and flaws that may have serious unintended consequences on public safety, workplaces, and federal funding. However, even if the proposition had passed, the sale of cannabis would have remained illegal under federal law via the Controlled Substances Act. [7] [8] [9]

The law of the United States comprises many levels of codified and uncodified forms of law, of which the most important is the United States Constitution, the foundation of the federal government of the United States. The Constitution sets out the boundaries of federal law, which consists of Acts of Congress, treaties ratified by the Senate, regulations promulgated by the executive branch, and case law originating from the federal judiciary. The United States Code is the official compilation and codification of general and permanent federal statutory law.

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) is the statute establishing federal U.S. drug policy under which the manufacture, importation, possession, use, and distribution of certain substances is regulated. It was passed by the 91st United States Congress as Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 and signed into law by President Richard Nixon. The Act also served as the national implementing legislation for the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

Proposition 19 was followed up by the Adult Use of Marijuana Act in 2016. [10]

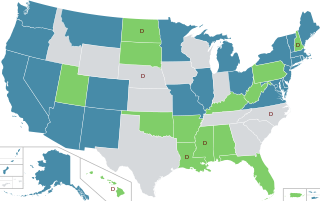

The Adult Use of Marijuana Act (AUMA) was a 2016 voter initiative to legalize cannabis in California. The full name is the Control, Regulate and Tax Adult Use of Marijuana Act. The initiative passed with 57% voter approval and became law on November 9, 2016, leading to recreational cannabis sales in California by January 2018.