Related Research Articles

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultranationalist political ideology and movement, characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hierarchy, subordination of individual interests for the perceived good of the nation and race, and strong regimentation of society and the economy.

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration sentiment, as well as opposition to liberal democracy, social democracy, parliamentarianism, liberalism, Marxism, neoliberalism, communism, and socialism. As with classical fascism, it proposes a Third Position as an alternative to market capitalism.

Far-right politics, or right-wing extremism, refers to a spectrum of political thought that tends to be radically conservative, ultra-nationalist, and authoritarian, often also including nativist tendencies. The name derives from the left–right political spectrum, with the "far right" considered further from center than the standard political right.

Clerical fascism is an ideology that combines the political and economic doctrines of fascism with clericalism. The term has been used to describe organizations and movements that combine religious elements with fascism, receive support from religious organizations which espouse sympathy for fascism, or fascist regimes in which clergy play a leading role.

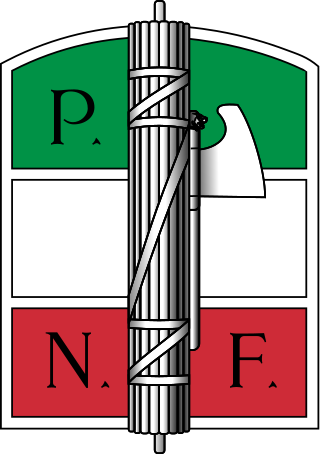

Fascist symbolism is the use of certain images and symbols which are designed to represent aspects of fascism. These include national symbols of historical importance, goals, and political policies. The best-known are the fasces, which was the original symbol of fascism, and the swastika of Nazism.

The history of fascist ideology is long and it draws on many sources. Fascists took inspiration from sources as ancient as the Spartans for their focus on racial purity and their emphasis on rule by an elite minority. Fascism has also been connected to the ideals of Plato, though there are key differences between the two. Fascism styled itself as the ideological successor to Rome, particularly the Roman Empire. From the same era, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's view on the absolute authority of the state also strongly influenced fascist thinking. The French Revolution was a major influence insofar as the Nazis saw themselves as fighting back against many of the ideas which it brought to prominence, especially liberalism, liberal democracy and racial equality, whereas on the other hand, fascism drew heavily on the revolutionary ideal of nationalism. The prejudice of a "high and noble" Aryan culture as opposed to a "parasitic" Semitic culture was core to Nazi racial views, while other early forms of fascism concerned themselves with non-racialized conceptions of the nation.

Historians and other scholars disagree on the question of whether a specifically fascist type of economic policy can be said to exist. David Baker argues that there is an identifiable economic system in fascism that is distinct from those advocated by other ideologies, comprising essential characteristics that fascist nations shared. Payne, Paxton, Sternhell et al. argue that while fascist economies share some similarities, there is no distinctive form of fascist economic organization. Gerald Feldman and Timothy Mason argue that fascism is distinguished by an absence of coherent economic ideology and an absence of serious economic thinking. They state that the decisions taken by fascist leaders cannot be explained within a logical economic framework.

Tōhōkai was a Japanese fascist political party. The party was active in Japan during the 1930s and early 1940s. Its origins lay in the right-wing political organization Kokumin Domei which was formed by Adachi Kenzō in 1933. In 1936, Nakano Seigō disagreed with Adachi on of matters of policy and formed a separate group, which he called the 'Tōhōkai'.

What constitutes as a definition of fascism and fascist governments has been a complicated and highly disputed subject concerning the exact nature of fascism and its core tenets debated amongst historians, political scientists, and other scholars ever since Benito Mussolini first used the term in 1915. Historian Ian Kershaw once wrote that "trying to define 'fascism' is like trying to nail jelly to the wall".

The National Fascist Party was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian fascism and as a reorganisation of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The party ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 when Fascists took power with the March on Rome until the fall of the Fascist regime in 1943, when Mussolini was deposed by the Grand Council of Fascism. It was succeeded, in the territories under the control of the Italian Social Republic, by the Republican Fascist Party, ultimately dissolved at the end of World War II.

Greyshirts or Gryshemde is the common short-form name given to the South African Gentile National Socialist Movement, a South African Nazi movement that existed during the 1930s and 1940s. Initially referring only to a paramilitary group, it soon became shorthand for the movement as a whole.

Fascist movements in Europe were the set of various fascist ideologies which were practised by governments and political organisations in Europe during the 20th century. Fascism was born in Italy following World War I, and other fascist movements, influenced by Italian Fascism, subsequently emerged across Europe. Among the political doctrines which are identified as ideological origins of fascism in Europe are the combining of a traditional national unity and revolutionary anti-democratic rhetoric which was espoused by the integral nationalist Charles Maurras and the revolutionary syndicalist Georges Sorel.

Fascist movements in Asia that adhered to fascist policies, which gained popularity in many countries in Asia during the 1920s.

Fascism has a long history in North America, with the earliest movements appearing shortly after the rise of Fascism in Europe. Fascist movements in North America never gained power, unlike their counterparts in Europe.

Fascism in South America is an assortment of political parties and movements modelled on fascism. Although originating and primarily associated with Europe, the ideology crossed the Atlantic Ocean in the interwar period and had an influence on South American politics. The original Italian fascism had a deep impact in the region. Although the ideas of Falangism probably had the deepest impact in South America, largely due to Hispanidad, more generic fascism was also an important factor in regional politics.

Fascism in Its Epoch, also known in English as The Three Faces of Fascism, is a 1963 book by historian and philosopher Ernst Nolte. It is widely regarded as his magnum opus and a seminal work on the history of fascism.

Some authors and historians have carried out comparisons of Nazism and Stalinism. They have considered the similarities and differences between the two ideologies and political systems, the relationship between the two regimes, and why both came to prominence simultaneously. During the 20th century, the comparison of Nazism and Stalinism was made on totalitarianism, ideology, and personality cult. Both regimes were seen in contrast to the liberal democratic Western world, emphasizing the similarities between the two.

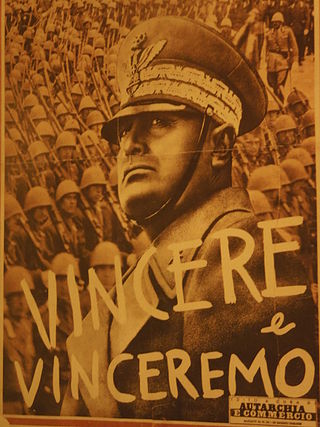

The Kingdom of Italy was governed by the National Fascist Party from 1922 to 1943 with Benito Mussolini as prime minister. The Italian Fascists imposed authoritarian rule and crushed political and intellectual opposition, while promoting economic modernization, traditional social values and a rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church.

References

- 1 2 3 Robert O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism , 2004, p. 191

- ↑ Roger Griffin, The Nature of Fascism, Routledge, 1991, p. 157

- ↑ Griffin, The Nature of Fascism, p. 156

- ↑ Paul M. Hayes, Fascism, London: Allen & Unwin, 1973, pp. 208-223

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism 1914-45, Routledge, 1995, pp. 514-515

- ↑ Payne, A History of Fascism, p. 515

- 1 2 Michel Ugarte. Africans in Europe: the culture of exile and emigration from Equatorial Guinea to Spain. University of Illinois Press, 2010. Pp. 25.

- 1 2 Christian P. Scherrer, Institute for Research on Ethnicity and Conflict Resolution. Ongoing crisis in Central Africa: revolution in Congo and disorder in the Great Lakes region: conflict impact assessment and policy options. Institute for Research on Ethnicity and Conflict Resolution, 1998. Pp. 83.

- 1 2 Front Cover Dina Temple-Raston. Justice on the Grass: Three Rwandan Journalists, Their Trial for War Crimes and a Nation's Quest for Redemption. Simon and Schuster, 2005. Pp. 170.

- 1 2 Raymond Verdier, Emmanuel Decaux, Jean-Pierre Chrétien (editors). "Situation judiciare au Rwanda" by Alphonse Marie Nkubito, Rwanda, un génocide du XXe siècle. Editions L'Harmattan, 1995. Pp. 223.

- ↑ Christoph Marx, 'The Ossewabrandwag As a Mass Movement, 1939-1941', Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Jun. 1994), p. 208

- ↑ G. Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black - Sir Oswald Mosley and the Resurrection of British Fascism after 1945, New York: IB Tauris, 2007, pp. 84-5

- ↑ "Sidney Robey Leibbrandt 1913 - 1966". Leibbrandt Archive. Retrieved July 20, 2006.

- ↑ Roger Griffin, The Nature of Fascism, 1993, p. 158

- ↑ Peter H. Merkl, Leonard Weinberg, The Revival of Right Wing Extremism in the Nineties, Routledge, 2014, p. 255

- 1 2 Roger Griffin, The Nature of Fascism, Routledge, 2013, p. 159

- ↑ Kathryn A. Manzo, Creating Boundaries: The Politics of Race and Nation, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998, p. 86

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne, Fascism in Europe, 1914-45, 2001, p. 45

- ↑ Payne, A History of Fascism, pp. 353

- ↑ Yaacov Shimoni & Evyatar Levine, Political Dictionary of the Middle East in the 20th Century, 1974, p. 250

- ↑ Payne, A History of Fascism, pp. 352

- ↑ R.J.B. Bosworth, The Oxford Handbook of Fascism, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 499

- ↑ Griffin, The Nature of Fascism, p. 165

- 1 2 Christian P. Scherrer. Ethnicity, nationalism, and violence: conflict management, human rights, and multilateral regimes. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003. Pp. 328

- ↑ "'The Hitler of Africa'". Archived from the original on 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ Idi Amin Dada: Hitler in Africa