In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone or pit, although many pips or seeds may be present. Common examples of berries in the culinary sense are strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, blackberries, red currants, white currants and blackcurrants. In Britain, soft fruit is a horticultural term for such fruits.

In botany, a drupe is an indehiscent type of fruit in which an outer fleshy part surrounds a single shell of hardened endocarp with a seed (kernel) inside. These fruits usually develop from a single carpel, and mostly from flowers with superior ovaries. Xylem fibres are dead and xylem parenchyma are living

An accessory fruit is a fruit that contains tissue derived from plant parts other than the ovary. In other words, the flesh of the fruit develops not from the floral ovary, but from some adjacent tissue exterior to the carpel. As a general rule, the accessory fruit is a combination of several floral organs, including the ovary. In contrast, true fruit forms exclusively from the ovary of the flower.

A nut is a fruit consisting of a hard or tough nutshell protecting a kernel which is usually edible. In general usage and in a culinary sense, a wide variety of dry seeds are called nuts, but in a botanical context "nut" implies that the shell does not open to release the seed (indehiscent).

An achene, also sometimes called akene and occasionally achenium or achenocarp, is a type of simple dry fruit produced by many species of flowering plants. Achenes are monocarpellate and indehiscent. Achenes contain a single seed that nearly fills the pericarp, but does not adhere to it. In many species, what is called the "seed" is an achene, a fruit containing the seed. The seed-like appearance is owed to the hardening of the fruit wall (pericarp), which encloses the solitary seed so closely as to seem like a seed coat.

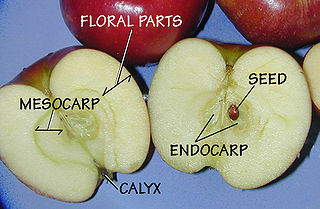

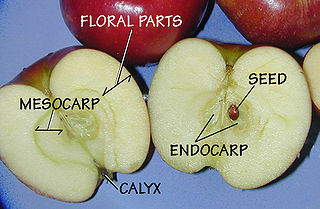

In botany, a pome is a type of fruit produced by flowering plants in the subtribe Malinae of the family Rosaceae. Pome fruits consist of a central "core" containing multiple small seeds, which is enveloped by a tough membrane and surrounded by an edible layer of flesh. Pome fruit trees are deciduous, and undergo a dormant winter period that requires cold temperatures to break dormancy in spring. Well-known pomes include the apple, pear, and quince.

Mangosteen, also known as the purple mangosteen, is a tropical evergreen tree with edible fruit native to tropical lands surrounding the Indian Ocean. Its origin is uncertain due to widespread prehistoric cultivation. It grows mainly in Southeast Asia, southwest India and other tropical areas such as Colombia and Puerto Rico, where the tree has been introduced.

An aril, also called an arillus, is a specialized outgrowth from a seed that partly or completely covers the seed. An arillode or false aril is sometimes distinguished: whereas an aril grows from the attachment point of the seed to the ovary, an arillode forms from a different point on the seed coat. The term "aril" is sometimes applied to any fleshy appendage of the seed in flowering plants, such as the mace of the nutmeg seed. Arils and arillodes are often edible enticements that encourage animals to transport the seed, thereby assisting in seed dispersal. Pseudarils are aril-like structures commonly found on the pyrenes of Burseraceae species that develop from the mesocarp of the ovary. The fleshy, edible pericarp splits neatly in two halves, then falling away or being eaten to reveal a brightly coloured pseudaril around the black seed.

Sclerocarya birrea, commonly known as the marula, is a medium-sized deciduous fruit-bearing tree, indigenous to the miombo woodlands of Southern Africa, the Sudano-Sahelian range of West Africa, the savanna woodlands of East Africa and Madagascar.

Mammea americana, commonly known as mammee, mammee apple, mamey, mamey apple, Santo Domingo apricot, tropical apricot, or South American apricot, is an evergreen tree of the family Calophyllaceae, whose fruit is edible. It has also been classified as belonging to the family Guttiferae Juss. (1789), which would make it a relative of the mangosteen.

Dehiscence is the splitting of a mature plant structure along a built-in line of weakness to release its contents. This is common among fruits, anthers and sporangia. Sometimes this involves the complete detachment of a part. Structures that open in this way are said to be dehiscent. Structures that do not open in this way are called indehiscent, and rely on other mechanisms such as decay or predation to release the contents.

In the flowering plants, an ovary is a part of the female reproductive organ of the flower or gynoecium. Specifically, it is the part of the pistil which holds the ovule(s) and is located above or below or at the point of connection with the base of the petals and sepals. The pistil may be made up of one carpel or of several fused carpels, and therefore the ovary can contain part of one carpel or parts of several fused carpels. Above the ovary is the style and the stigma, which is where the pollen lands and germinates to grow down through the style to the ovary, and, for each individual pollen grain, to fertilize one individual ovule. Some wind pollinated flowers have much reduced and modified ovaries.

In botany, a berry is a fleshy fruit without a stone (pit) produced from a single flower containing one ovary. Berries so defined include grapes, currants, and tomatoes, as well as cucumbers, eggplants (aubergines) and bananas, but exclude certain fruits that meet the culinary definition of berries, such as strawberries and raspberries. The berry is the most common type of fleshy fruit in which the entire outer layer of the ovary wall ripens into a potentially edible "pericarp". Berries may be formed from one or more carpels from the same flower. The seeds are usually embedded in the fleshy interior of the ovary, but there are some non-fleshy exceptions, such as Capsicum species, with air rather than pulp around their seeds.

Zest is a food ingredient that is prepared by scraping or cutting from the rind of unwaxed citrus fruits such as lemon, orange, citron, and lime. Zest is used to add flavor to foods.

Peel, also known as rind or skin, is the outer protective layer of a fruit or vegetable which can be peeled off. The rind is usually the botanical exocarp, but the term exocarp also includes the hard cases of nuts, which are not named peels since they are not peeled off by hand or peeler, but rather shells because of their hardness.

This page provides a glossary of plant morphology. Botanists and other biologists who study plant morphology use a number of different terms to classify and identify plant organs and parts that can be observed using no more than a handheld magnifying lens. This page provides help in understanding the numerous other pages describing plants by their various taxa. The accompanying page—Plant morphology—provides an overview of the science of the external form of plants. There is also an alphabetical list: Glossary of botanical terms. In contrast, this page deals with botanical terms in a systematic manner, with some illustrations, and organized by plant anatomy and function in plant physiology.

Prunus rivularis, known variously by the common names creek plum, hog plum, or wild-goose plum is a thicket-forming shrub. It prefers calcareous clay soil or limestone-based woodland soils. This deciduous plant belongs to the rose family, Rosaceae, and is found mainly in the central United States. It is a shrub consisting of slender stems with umbel clusters of white blossoms. The fruit is a drupe that resembles a large berry; though it has a bitter taste, it serves as a source of food for birds and other wildlife. "Prunus" is Latin for plum, whereas "rivularis" means being near a stream.