Loudon County is a county in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is located in the central part of East Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 54,886. Its county seat is Loudon. Loudon County is included in the Knoxville, TN Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Vonore is a town in Monroe County, Tennessee, which is located on the southeast border of the state. The population was 1,574 as of the 2020 census. The city hall, library, community center, police department, and fire department are located on Church Street.

The Little Tennessee River is a 135-mile (217 km) tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Georgia, into North Carolina, and then into Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It drains portions of three national forests— Chattahoochee, Nantahala, and Cherokee— and provides the southwestern boundary of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Chota is a historic Overhill Cherokee town site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Developing after nearby Tanasi, Chota was the most important of the Overhill towns from the late 1740s until 1788. It replaced Tanasi as the de facto capital, or 'mother town' of the Cherokee people.

Tanasi was a historic Overhill settlement site in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The village became the namesake for the state of Tennessee. It was abandoned by the Cherokee in the 19th century for a rising town whose chief was more powerful. Tanasi served as the de facto capital of the Overhill Cherokee from as early as 1721 until 1730, when the capital shifted to Great Tellico.

Morganton was a community that developed on the Little Tennessee River in Loudon County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It was located 13.7 miles (22.0 km) above the mouth of the river at its confluence with Bakers Creek, flowing westward from Maryville. During its heyday in the 19th century, Morganton thrived as a flatboat port and regional business center. An important ferry operated at Morganton for nearly 170 years providing service across the river. The abandoned townsite was submerged in the late 20th century by creation of Tellico Lake, part of the Tellico Dam hydroelectric project completed in 1979 by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

The Bat Creek inscription is an inscribed stone tablet found by John W. Emmert on February 14, 1889. Emmert claimed to have found the tablet in Tipton Mound 3 during an excavation of Hopewell mounds in Loudon County, Tennessee. This excavation was part of a larger series of excavations that aimed to clarify the controversy regarding who is responsible for building the various mounds found in the Eastern United States.

The Tellico Blockhouse was an early American outpost located along the Little Tennessee River in what developed as Vonore, Monroe County, Tennessee. Completed in 1794, the blockhouse was a US military outpost that operated until 1807; the garrison was intended to keep peace between the nearby Overhill Cherokee towns and encroaching early Euro-American pioneers in the area in the wake of the Cherokee–American wars.

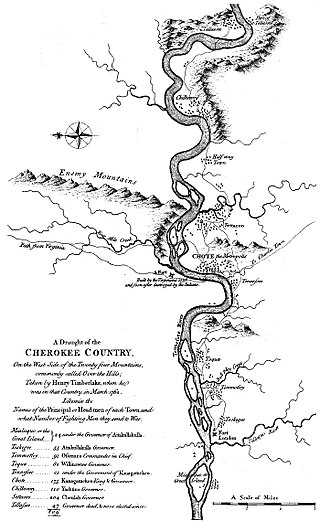

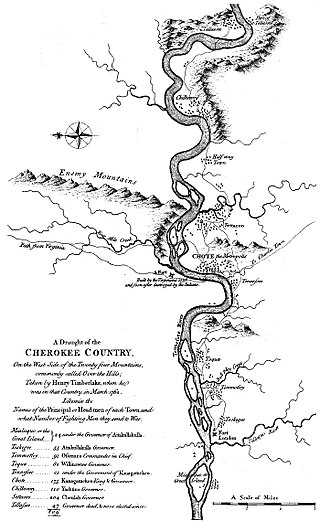

Overhill Cherokee was the term for the Cherokee people located in their historic settlements in what is now the U.S. state of Tennessee in the Southeastern United States, on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. This name was used by 18th-century European traders and explorers from British colonies along the Atlantic coast, as they had to cross the mountains to reach these settlements.

Toqua was a prehistoric and historic Native American site in Monroe County, Tennessee, located in the Southeastern Woodlands. Toqua was the site of a substantial ancestral town that thrived during the Mississippian period. Toqua had a large earthwork 25-foot (7.6 m) platform mound built by the town's Mississippian-era inhabitants, in addition to a second, smaller mound. The site's Mississippian occupation may have been recorded by the Spanish as the village of Tali, which was documented in 1540 by the Hernando de Soto expedition. It was later known as the Overhill Cherokee town Toqua, and this name was applied to the archeological site.

Tomotley is a prehistoric and historic Native American site along the lower Little Tennessee River in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Occupied as early as the Archaic period, the Tomotley site was occupied particularly during the Mississippian period, which was likely when its earthwork platform mounds were built. It was also occupied during the eighteenth century as a Cherokee town. It revealed an unexpected style: an octagonal townhouse and square or rectangular residences. In the Overhill period, Cherokee townhouses found in the Carolinas in the same period were circular in design, with,

Citico is a prehistoric and historic Native American site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The site's namesake Cherokee village was the largest of the Overhill towns, housing an estimated Indian population of 1,000 by the mid-18th century. The Mississippian village that preceded the site's Cherokee occupation is believed to have been the village of "Satapo" visited by the Juan Pardo expedition in 1567.

Mialoquo is a prehistoric and historic Native American site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The site saw significant periods of occupation during the Mississippian period and later as a Cherokee refugee village. While the archaeological site of Mialoquo was situated on the southwest bank of the Little Tennessee River, the village's habitation area probably included part of Rose Island, a large island in the river immediately opposite the site. Rose Island was occupied on at least a semi-permanent basis as early as the Middle Archaic period.

Carson Brewer was an American journalist and conservationist, best known for his work documenting the folk life of Knoxville and the surrounding Appalachian communities in East Tennessee. During his 40-year career as a columnist for the Knoxville News-Sentinel, Brewer was a key voice for the promotion and protection of the region's natural wonders, especially the Great Smoky Mountains. His historical work included the first extensive history of the Little Tennessee River valley and one of the first comprehensive histories of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Bussell Island, formerly Lenoir Island, is an island located at the mouth of the Little Tennessee River, at its confluence with the Tennessee River in Loudon County, near the U.S. city of Lenoir City, Tennessee. The island was inhabited by various Native American cultures for thousands of years before the arrival of early European explorers. The Tellico Dam and a recreational area occupy part of the island. Part of the island was added in 1978 to the National Register of Historic Places for its archaeological potential.

Jefferson Chapman is an archaeologist who conducted extensive excavations at sites in eastern Tennessee, recovering evidence that provided the first secure radiocarbon chronology for Early and Middle Archaic period assemblages in Eastern North America. He also is a research professor in anthropology and the Director of the Frank H. McClung Museum at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Chapman’s professional interests include Southeastern archaeology, paleoethnobotany, museology and public archaeology.