Lombardy is an administrative region of Italy that covers 23,844 km2 (9,206 sq mi); it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is located between the Alps mountain range and tributaries of the river Po, and includes Milan, its capital, the largest metropolitan area in the country, and among the largest in the EU.

The Lombard language belongs to the Gallo-Italic group within the Romance languages. It is characterized by a Celtic linguistic substratum and a Lombardic linguistic superstratum and is a cluster of homogeneous dialects that are spoken by millions of speakers in Northern Italy and southern Switzerland. These include most of Lombardy and some areas of the neighbouring regions, notably the far eastern side of Piedmont and the extreme western side of Trentino, and in Switzerland in the cantons of Ticino and Graubünden. The language is also spoken in Santa Catarina in Brazil by Lombard immigrants from the Province of Bergamo, in Italy.

Tommaso Grossi was an Italian poet and novelist.

Western Lombard is a group of dialects of Lombard, a Romance language spoken in Italy. It is widespread in the Lombard provinces of Milan, Monza, Varese, Como, Lecco, Sondrio, a small part of Cremona, Lodi and Pavia, and the Piedmont provinces of Novara, Verbano-Cusio-Ossola, the eastern part of the Province of Alessandria (Tortona), a small part of Vercelli (Valsesia), and Switzerland. After the name of the region involved, land of the former Duchy of Milan, this language is often referred to as Insubric or Milanese, or, after Clemente Merlo, Cisabduano.

The Bergamasque dialect is the western variant of the Eastern Lombard group of the Lombard language. It is mainly spoken in the province of Bergamo and in the area around Crema, in central Lombardy.

Carlo Porta was an Italian poet, the most famous writer in Milanese.

Brianzöö or Brianzoeu is a group of variants of the Western variety of the Lombard language, spoken in the region of Brianza.

Canzés is a variety of Brianzöö spoken in the commune of Canzo, Italy.

Eastern Lombard is a group of closely related variants of Lombard, a Gallo-Italic language spoken in Lombardy, mainly in the provinces of Bergamo, Brescia and Mantua, in the area around Cremona and in parts of Trentino. Its main variants are Bergamasque and Brescian.

Delio Tessa was an Italian poet from Milan who wrote dialect poetry.

The classical Milanese orthography is the orthography used for the Western Lombard language, in particular for the Milanese dialect, by the major poets and writers of this literature, such as Carlo Porta, Carlo Maria Maggi, Delio Tessa, etc. It was first used in the seventeenth century by Carlo Maria Maggi; Maggi first introduced the trigram oeu, while previous authors, like Bonvesin de la Riva, used Latinizing orthographies. In 1606 G. A. Biffi with his Prissian de Milan de la parnonzia milanesa began the first codification, incorporating vowel length and the use of ou to represent the sound. The classical orthography came as a compromise between the old Tuscan system and the French one; the characteristic that considerably differentiates this orthography from the effective pronunciation is the method for the distinction of long and short vowels. As of today, because it has become more archaic, it is often replaced by simpler methods that use signs ö, ü for front rounded vowels and the redoubling of vowels for long vowels. The classical orthography was regularized in the 1990s by the Circolo Filologico Milanese for modern use.

Southwestern Lombard is a group of dialects of Western Lombard language spoken in the provinces of Pavia, Lodi, Novara, Cremona, in the south of the historic Insubria, and comprises Pavese, Ludesan, Novarese, Cremunés and others.

Pavese is a dialect of Western Lombard language spoken in province of Pavia (Lombardy). In Pavese, differently from most of Western Lombard dialects, the "z" is transformed into "s".

Spasell is a slang of Insubric language, spoken until the 19th century by inhabitants of Vallassina, when they used to go out from the valley for business and they didn't want to be understood by the people. It is characterized by code-words conventionally defined basing on characteristics of the thing or on onomatopoeias; other words have an unknown origin. It has been noted by Carlo Mazza, vicar of Asso, in his book Memorie storiche della Vallassina of 1796. He informs us that several slangs have been created in the time, because in the time the words were introduced in the current language, reducing the differences between "official" language and "secret" language. After a list of terms, the vicar proposes, as example, the translation of Pater Noster in this language, evidencing that it's totally incomprehensible also by the Insubric speakers. There are various similar or identical slangs in many localities of Insubria, like Valtellina and Milan. Some Spasell words have been adsorbed by the common language, for example lòfi, used in northern Brianza to indicate a "so and so" person, or scabbi, used also by Carlo Porta in the poem Brindes de Meneghin a l'Ostaria to refer to wine, in alternation with vin.

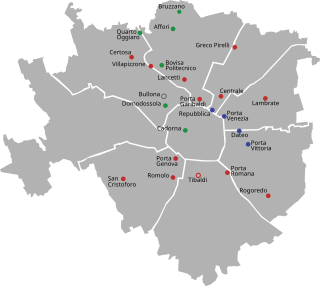

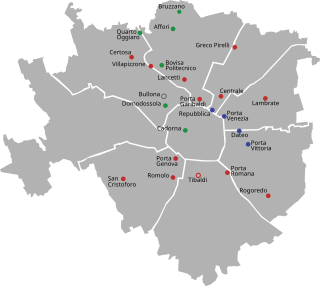

Milan has 24 railway stations in use today. Of these, 18 are managed by RFI, while the remaining 6 are operated by Ferrovienord. Three more stations are currently in the planning stage for the city area: Canottieri, Dergano and Zama.

Carlo Maria Maggi was an Italian scholar, writer and poet. Despite being an Accademia della Crusca affiliate, he gained his fame as an author of "dialectal" works in Milanese language, for which he is considered the father of Milanese literature. Maggi's work was a major inspiration source for later Milanese scholars such as Carlo Porta and Giuseppe Parini.

The bosinada or bosinata was a traditional, popular poetic genre in Lombard language that began in the 18th century or earlier and reached its apex in the late 19th century. Bosinate were usually written or printed on sheets of paper and recited by a sort of cantastorie or minstrel called a bosin ; they were usually satirical in content, sometimes explicitly designed to hold someone up to ridicule, or to debunk certain social habits or circumstances; in any case, they were the expression of the naive but sound good sense of the common people.

Lombard nationalism is a nationalist, but primarily regionalist, movement active primarily in Lombardy, Italy. It seeks more autonomy or even independence from Italy for Lombardy and, possibly, all the lands that are linguistically or historically Lombard. During the 1990s, it was strictly connected with Padanian nationalism.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Milan:

Legnanese dialect is a dialect of the Lombard language that is spoken around Legnano, a municipality in the metropolitan city of Milan, Lombardy. It is spoken by about 30 percent of the population of the area in which it is spread.