A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and enable mobility. Bones come in a variety of shapes and sizes and have complex internal and external structures. They are lightweight yet strong and hard and serve multiple functions.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH), also called parathormone or parathyrin, is a peptide hormone secreted by the parathyroid glands that regulates the serum calcium concentration through its effects on bone, kidney, and intestine.

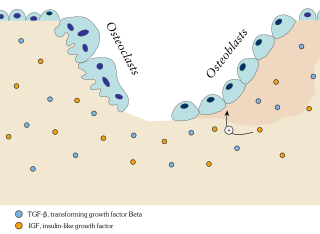

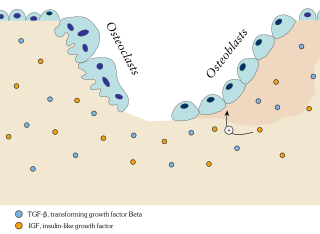

An osteoclast is a type of bone cell that breaks down bone tissue. This function is critical in the maintenance, repair, and remodeling of bones of the vertebral skeleton. The osteoclast disassembles and digests the composite of hydrated protein and mineral at a molecular level by secreting acid and a collagenase, a process known as bone resorption. This process also helps regulate the level of blood calcium.

Bisphosphonates are a class of drugs that prevent the loss of bone density, used to treat osteoporosis and similar diseases. They are the most commonly prescribed drugs used to treat osteoporosis. They are called bisphosphonates because they have two phosphonate groups. They are thus also called diphosphonates.

An osteocyte, an oblate shaped type of bone cell with dendritic processes, is the most commonly found cell in mature bone. It can live as long as the organism itself. The adult human body has about 42 billion of them. Osteocytes do not divide and have an average half life of 25 years. They are derived from osteoprogenitor cells, some of which differentiate into active osteoblasts. Osteoblasts/osteocytes develop in mesenchyme.

Bone resorption is resorption of bone tissue, that is, the process by which osteoclasts break down the tissue in bones and release the minerals, resulting in a transfer of calcium from bone tissue to the blood.

Receptor activator of nuclear factor κ B (RANK), also known as TRANCE receptor or TNFRSF11A, is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) molecular sub-family. RANK is the receptor for RANK-Ligand (RANKL) and part of the RANK/RANKL/OPG signaling pathway that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. It is associated with bone remodeling and repair, immune cell function, lymph node development, thermal regulation, and mammary gland development. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a decoy receptor for RANKL, and regulates the stimulation of the RANK signaling pathway by competing for RANKL. The cytoplasmic domain of RANK binds TRAFs 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 which transmit signals to downstream targets such as NF-κB and JNK.

Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL), also known as tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 11 (TNFSF11), TNF-related activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE), osteoprotegerin ligand (OPGL), and osteoclast differentiation factor (ODF), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TNFSF11 gene.

Denosumab, sold under the brand names Prolia and Xgeva among others, is a human monoclonal antibody used for the treatment of osteoporosis, treatment-induced bone loss, metastases to bone, and giant cell tumor of bone.

Toll-like receptor 5, also known as TLR5, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the TLR5 gene. It is a member of the toll-like receptor (TLR) family. TLR5 is known to recognize bacterial flagellin from invading mobile bacteria. It has been shown to be involved in the onset of many diseases, including Inflammatory bowel disease due to the high expression of TLR in intestinal lamina propria dendritic cells. Recent studies have also shown that malfunctioning of TLR5 is likely related to rheumatoid arthritis, osteoclastogenesis, and bone loss. Abnormal TLR5 functioning is related to the onset of gastric, cervical, endometrial and ovarian cancers.

Osteoimmunology is a field that emerged about 40 years ago that studies the interface between the skeletal system and the immune system, comprising the "osteo-immune system". Osteoimmunology also studies the shared components and mechanisms between the two systems in vertebrates, including ligands, receptors, signaling molecules and transcription factors. Over the past decade, osteoimmunology has been investigated clinically for the treatment of bone metastases, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoporosis, osteopetrosis, and periodontitis. Studies in osteoimmunology reveal relationships between molecular communication among blood cells and structural pathologies in the body.

Ipriflavone is a synthetic isoflavone which may be used to inhibit bone resorption, maintain bone density and to prevent osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. It is not used to treat osteoporosis. It slows down the action of the osteoclasts, possibly allowing the osteoblasts to build up bone mass.

In osteology, bone remodeling or bone metabolism is a lifelong process where mature bone tissue is removed from the skeleton and new bone tissue is formed. These processes also control the reshaping or replacement of bone following injuries like fractures but also micro-damage, which occurs during normal activity. Remodeling responds also to functional demands of the mechanical loading.

Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), also known as macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (M-CSFR), and CD115, is a cell-surface protein encoded by the human CSF1R gene. CSF1R is a receptor that can be activated by two ligands: colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) and interleukin-34 (IL-34). CSF1R is highly expressed in myeloid cells, and CSF1R signaling is necessary for the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of many myeloid cell types in vivo and in vitro. CSF1R signaling is involved in many diseases and is targeted in therapies for cancer, neurodegeneration, and inflammatory bone diseases.

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw is progressive death of the jawbone in a person exposed to a medication known to increase the risk of disease, in the absence of a previous radiation treatment. It may lead to surgical complication in the form of impaired wound healing following oral and maxillofacial surgery, periodontal surgery, or endodontic therapy.

Resorption of the root of the tooth, or root resorption, is the progressive loss of dentin and cementum by the action of odontoclasts. Root resorption is a normal physiological process that occurs in the exfoliation of the primary dentition. However, pathological root resorption occurs in the permanent or secondary dentition and sometimes in the primary dentition.

Nikos Athanasou is a short story writer and novelist and musculoskeletal pathologist and scientist. He was born in Perth and grew up in Sydney where he studied medicine. He moved to England and is currently Professor of Musculoskeletal Pathology at Oxford University and a Fellow of Wadham College.

The human skeletal system is a complex organ in constant equilibrium with the rest of the body. In addition to support and structure of the body, bone is the major reservoir for many minerals and compounds essential for maintaining a healthy pH balance. The deterioration of the body with age renders the elderly particularly susceptible to and affected by poor bone health. Illnesses like osteoporosis, characterized by weakening of the bone's structural matrix, increases the risk of hip-fractures and other life-changing secondary symptoms. In 2010, over 258,000 people aged 65 and older were admitted to the hospital for hip fractures. Incidence of hip fractures is expected to rise by 12% in America, with a projected 289,000 admissions in the year 2030. Other sources estimate up to 1.5 million Americans will have an osteoporotic-related fracture each year. The cost of treating these people is also enormous, in 1991 Medicare spent an estimated $2.9 billion for treatment and out-patient care of hip fractures, this number can only be expected to rise.

A bone growth factor is a growth factor that stimulates the growth of bone tissue.

An osteolytic lesion is a softened section of a patient's bone formed as a symptom of specific diseases, including breast cancer and multiple myeloma. This softened area appears as a hole on X-ray scans due to decreased bone density, although many other diseases are associated with this symptom. Osteolytic lesions can cause pain, increased risk of bone fracture, and spinal cord compression. These lesions can be treated using biophosphonates or radiation, though new solutions are being tested in clinical trials.