Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia included indigenous Arabian polytheism, ancient Semitic religions, Christianity, Judaism, Mandaeism, and Zoroastrianism.

According to Greek mythology, the Korybantes or Corybantes were the armed and crested dancers who worshipped the Phrygian goddess Cybele with drumming and dancing. They are also called the Kurbantes in Phrygia.

Elagabalus, Aelagabalus, Heliogabalus, or simply Elagabal was an Arab-Roman sun god, initially venerated in Emesa, Syria. Although there were many variations of the name, the god was consistently referred to as Elagabalus in Roman coins and inscriptions from AD 218 on, during the reign of emperor Elagabalus.

Asherah is the great goddess in ancient Semitic religion. She also appears in Hittite writings as Ašerdu(s) or Ašertu(s). Her name was Aṯeratum to the Amorites, and Athiratu in Ugarit. Significantly, Yahweh and Asherah were a consort pair in ancient Israel and Judah.

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been questioned as anachronistic. The ancient Greeks did not have a word for 'religion' in the modern sense. Likewise, no Greek writer known to us classifies either the gods or the cult practices into separate 'religions'. Instead, for example, Herodotus speaks of the Hellenes as having "common shrines of the gods and sacrifices, and the same kinds of customs."

Cattle are prominent in some religions and mythologies. As such, numerous peoples throughout the world have at one point in time honored bulls as sacred. In the Sumerian religion, Marduk is the "bull of Utu". In Hinduism, Shiva's steed is Nandi, the Bull. The sacred bull survives in the constellation Taurus. The bull, whether lunar as in Mesopotamia or solar as in India, is the subject of various other cultural and religious incarnations as well as modern mentions in New Age cultures.

An Asherah pole is a sacred tree or pole that stood near Canaanite religious locations to honor the goddess Asherah. The relation of the literary references to an asherah and archaeological finds of Judaean pillar-figurines has engendered a literature of debate.

The Canaanite religion was the group of ancient Semitic religions practiced by the Canaanites living in the ancient Levant from at least the early Bronze Age to the first centuries CE. Canaanite religion was polytheistic and, in some cases, monolatristic.

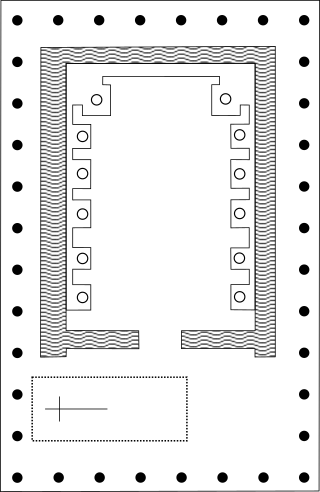

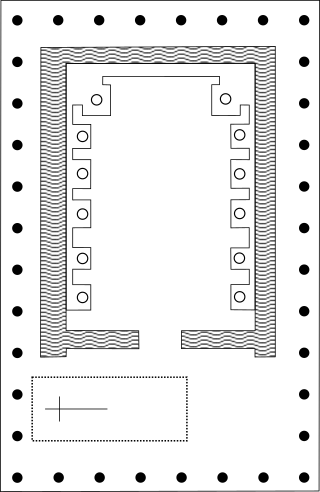

A temenos is a piece of land cut off and assigned as an official domain, especially to kings and chiefs, or a piece of land marked off from common uses and dedicated to a god, such as a sanctuary, holy grove, or holy precinct.

Psychro Cave is an ancient Minoan sacred cave in Lasithi plateau in the Lasithi district of eastern Crete. Psychro is associated with the Diktaean Cave, one of the putative sites of the birth of Zeus. Other legends place Zeus' birthplace as Idaean Cave on Mount Ida. According to Hesiod, Theogony, Rhea gave birth to Zeus in Lyctus and hid him in a cave of Mount Aegaeon. Since the late nineteenth century the cave above the modern village of Psychro has been identified with Diktaean Cave, although there are other candidates, especially a cave above Palaikastro on Mount Petsofas.

The Elagabalium was a temple built by the Roman emperor Elagabalus, located on the north-east corner of the Palatine Hill. During Elagabalus' reign from 218 until 222, the Elagabalium was the center of a controversial religious cult, dedicated to Elagabalus, of which the emperor himself was the high priest.

Minoan religion was the religion of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization of Crete. In the absence of readable texts from most of the period, modern scholars have reconstructed it almost totally on the basis of archaeological evidence of such as Minoan paintings, statuettes, vessels for rituals and seals and rings. Minoan religion is considered to have been closely related to Near Eastern ancient religions, and its central deity is generally agreed to have been a goddess, although a number of deities are now generally thought to have been worshipped. Prominent Minoan sacred symbols include the bull and the horns of consecration, the labrys double-headed axe, and possibly the serpent.

"Horns of Consecration" is a term coined by Sir Arthur Evans for the symbol, ubiquitous in Minoan civilization, that is usually thought to represent the horns of the sacred bull. Sir Arthur Evans concluded, after noting numerous examples in Minoan and Mycenaean contexts, that the Horns of Consecration were "a more or less conventionalised article of ritual furniture derived from the actual horns of the sacrificial oxen".

Velchanos is an ancient Minoan god associated with vegetation and worshipped in Crete. He was one of the main deities in the Minoan pantheon, alongside a Mother Goddess figure who appears to have been his mother and consort, with the two participating in an hieros gamos.

Roussolakkos is the site of a Minoan city, located near Palekastro, Crete. The Bronze Age town was occupied from Early Minoan IIA to Late Minoan IIIB, and its remains are relatively well preserved. A later Greek temple to Diktaian Zeus was built at the nearby Elaea promontory.

The Hagia Triada Sarcophagus is a late Minoan 137 cm (54 in)-long limestone sarcophagus, dated to around 1400 BC or some decades later, excavated from a chamber tomb at Hagia Triada, Crete in 1903 and now on display at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum (AMH) in Crete, Greece.

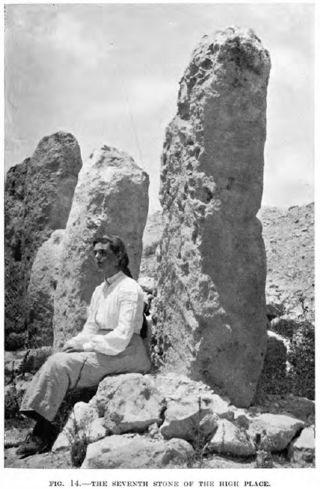

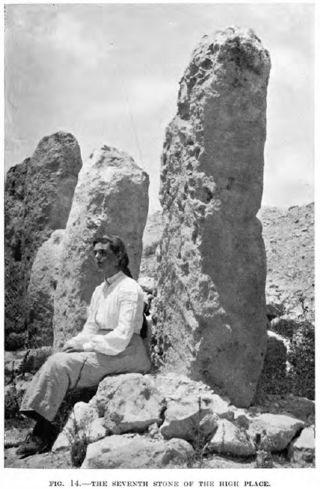

Matzevah or masseba is a term used in the Hebrew Bible for a sacred pillar, a type of standing stone. The term has been adopted by archaeologists for Israelite contexts, seldom for related cultures, such as the Canaanite and the Nabataean ones. As a second derived meaning, it is also used for a headstone or tombstone marking a Jewish grave.

The Palaikastro Kouros is a chryselephantine statuette of a male youth (kouros) excavated in stages in the modern-day town of Palaikastro on the Greek island of Crete. It has been dated to the Late Minoan 1B period in the mid-15th century BC, during the Bronze Age. It is now on display in the Archaeological Museum of Siteia. Standing roughly 50 cm tall, its large size by the standards of other figurines in Minoan art, and the value of its materials may indicate that it was a cult image for worship, the only one known from the Minoan civilization.

A ceremonial pole is a stake or post utilised or venerated as part of a ceremony or religious ritual. Ceremonial poles may symbolize a variety of concepts in different ceremonies and rituals practiced by a variety of cultures around the world.

The Nabataean religion was a form of Arab polytheism practiced in Nabataea, an ancient Arab nation which was well settled by the third century BCE and lasted until the Roman annexation in 106 CE. The Nabateans were polytheistic and worshipped a wide variety of local gods as well as Baalshamin, Isis, and Greco-Roman gods such as Tyche and Dionysus. They worshipped their gods at temples, high places, and betyls. They were mostly aniconic and preferred to decorate their sacred places with geometric designs. Much knowledge of the Nabataeans’ grave goods has been lost due to extensive looting throughout history. They made sacrifices to their gods, performed other rituals and believed in an afterlife.