Orphic Dionysus Zagreus

The Zagreus from the Euripides fragment is suggestive of Dionysus, the wine god son of Zeus and Semele, [22] and in fact, although it seems not to occur anywhere in Orphic sources, the name “Zagreus” is elsewhere identified with an Orphic Dionysus, who had a very different tradition from the standard one. [23] This Dionysus Zagreus was a son of Zeus and Persephone who was, as an infant, attacked and dismembered by the Titans, [24] but later reborn as the son of Zeus and Semele. [25] This dismemberment of Dionysus Zagreus (the sparagmos ), taken together with an assumed Orphic anthropogony, in which human beings arose from the ashes of the Titans (who had been struck by Zeus with his thunderbolt in punishment for the dismembering), is sometimes called the "Zagreus myth". [26] This story has often been considered the most important myth of Orphism, [27] and has been described as "one of the most enigmatic and intriguing of all Greek myths". [28]

The sparagmos

As pieced together from various ancient sources, the reconstructed story of the sparagmos, that is the dismemberment of Dionysus Zagreus, usually given by modern scholars, goes as follows. [29] Zeus had intercourse with Persephone in the form of a serpent, producing Dionysus. He is taken to Mount Ida where (like the infant Zeus) he is guarded by the dancing Curetes. Zeus intended Dionysus to be his successor as ruler of the cosmos, but a jealous Hera incited the Titans to kill the child. Distracting the infant Dionysus with various toys, including a mirror, the Titans seized Dionysus and tore (or cut) [30] him to pieces. The pieces were then boiled, roasted and partially eaten, by the Titans. But Athena managed to save Dionysus' heart, by which Zeus was able to contrive his rebirth from Semele.

Although the extant Orphic sources do not mention the name "Zagreus" in connection with this dismembered Dionysus (or anywhere else), the (c. 3rd century BC) poet Callimachus perhaps did. [31] We know that Callimachus, as well as his contemporary Euphorion, told the story of the dismembered child, [32] and Byzantine sources quote Callimachus as referring to the birth of a "Dionysos Zagreus", explaining that "Zagreus" was the poet's name for a chthonic Dionysus, the son of Zeus by Persephone. [33] The earliest certain identification of Zagreus with the dismembered Dionysus occurs in the writings of the late 1st century – early 2nd century AD biographer and essayist Plutarch, who mentions "Zagreus" as one of the names given to the figure by Delphic theologians. [34] Later, in the 5th century AD, the Greek epic poet Nonnus, who tells the story of this Orphic Dionysus, calls him the "older Dionysos ... illfated Zagreus", [35] "Zagreus the horned baby", [36] "Zagreus, the first Dionysos", [37] "Zagreus the ancient Dionysos", [38] and "Dionysos Zagreus", [39] and the 6th-century AD Pseudo-Nonnus similarly refers to the dismembered Dionysus as "Dionysus Zagreus". [40]

The 1st century BC historian Diodorus Siculus says that according to "some writers of myths" there were two gods named Dionysus, an older one, who was the son of Zeus and Persephone, [41] but that the "younger one [born to Zeus and Semele] also inherited the deeds of the older, and so the men of later times, being unaware of the truth and being deceived because of the identity of their names thought there had been but one Dionysus." [42]

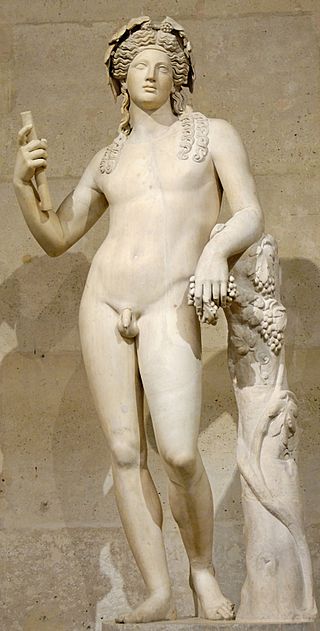

According to Diodorus, this older Dionysus, was represented in painting and sculpture with horns, because he "excelled in sagacity and was the first to attempt the yoking of oxen and by their aid to effect the sowing of the seed", [43] and the younger was "called Dimetor (Of Two Mothers) ... because the two Dionysoi were born of one father, but of two mothers". [44] He also said that Dionysus "was thought to have two forms ... the ancient one having a long beard, because all men in early times wore long beards, the younger one being youthful and effeminate and young." [45]

Cooking / eating

Several accounts of the myth involved the Titans cooking and/or eating at least part of Dionysus. [46] In the account attributed to Callimachus and Euphorion, the dismembered pieces of Dionysus were boiled in a cauldron, and Euphorion is quoted as saying that the pieces of Dionysus were placed over a fire. [47] Diodorus also says that the pieces were "boiled", [48] and the late 2nd century Christian writer Clement of Alexandria says that the pieces were "first boiled" in a cauldron, then pierced with spits and roasted. [49] Arnobius, an early 4th century Christian apologist, says that Dionysus' severed parts were "thrown into pots that he might be cooked". [50] None of these sources mention any actual eating, but other sources do. Plutarch says that the Titans "tasted his blood", [51] the 6th century AD Neoplatonist Olympiodorus says that they ate "his flesh", [52] and according to the 4th century euhemeristic account of the Latin astrologer and Christian apologist Firmicus Maternus, the Titans cooked the "members in various ways and devoured them" (membra consumunt), except for his heart. [53]

Resurrection / rebirth

In the version of the story apparently told by Callimachus and Euphorion, the cauldron containing the boiled pieces of Dionysus, is given to Apollo for burial, who placed it beside his tripod at Delphi. [54] And according to Philodemus, citing Euphorion, the pieces of Dionysus were "reassembled by Rhea, and brought back to life", [55] while according to Diodorus Siculus, the reassembly and resurrection of Dionysus was accomplished by Demeter. [56] Later Orphic sources have Apollo receive Dionysus' remains from Zeus, rather than the Titans, and it was Apollo who reassembled Dionysus, rather than Rhea or Demeter. [57]

In the accounts of Clement, and Firmicus Maternus cited above, as well as Proclus, [58] and a scholium on Lycophron 355, [59] Athena manages to save the heart of Dionysus, from which, according to Clement and the scholium, Athena received the name Pallas from the still beating (πάλλειν) heart. In Proclus' account Athena takes the heart to Zeus, and Dionysus is born again from Semele. According to Hyginus, Jupiter (the Roman equivalent of Zeus) "ground up his heart, put it in a potion, and gave it to Semele to drink", and she became pregnant with Dionysus. [60]

Osiris

In the interpretatio graeca Dionysus is often identified with the Egyptian god Osiris, [61] and stories of the dismemberment and resurrection of Osiris parallel those of Dionysus Zagreus. [62] According to Diodorus Siculus, [63] Egyptian myths about Priapus said that the Titans conspired against Osiris, killed him, divided his body into equal parts, and "slipped them secretly out of the house". All but Osiris' penis, which since none of them "was willing to take it with him", they threw into the river. Isis, Osiris' wife, hunted down and killed the Titans, reassembled Osiris' body parts "into the shape of a human figure", and gave them "to the priests with orders that they pay Osiris the honours of a god". But since she was unable to recover the penis she ordered the priests "to pay to it the honours of a god and to set it up in their temples in an erect position." [64]

Allegorical accounts

Diodorus Siculus reports an allegorical interpretation of the myth of the dismemberment of Dionysus as representing the production of wine. Diodorus knew of a tradition whereby this Orphic Dionysus was the son of Zeus and Demeter, rather than Zeus and Persephone. [65] This parentage was explained allegorically by identifying Dionysus with the grape vine, Demeter with the earth, and Zeus with the rain, saying that "the vine gets its growth both from the earth and from rains and so bears as its fruit the wine which is pressed out from the clusters of grapes". According to Diodorus, Dionysus' dismemberment by the Titans represented the harvesting of the grapes, and the subsequent "boiling" of his dismembered parts "has been worked into a myth by reason of the fact that most men boil the wine and then mix it, thereby improving its natural aroma and quality."

The Neronian-era Stoic Cornutus relates a similar allegorical interpretation, whereby the dismemberment represented the crushing of the grapes, and the rejoining of the dismembered pieces into a single body, represented the pouring of the juice into a single container. [66]

Rationalized accounts

Diodorus also reports a rationalized account of the older Dionysus. [67] In this account this Dionysus was a wise man, who was the inventor of the plough, as well as many other agricultural inventions. And according to Diodorus, these inventions, which greatly reduced manual labor, so pleased the people that they "accorded to him honours and sacrifices like those offered to the gods, since all men were eager, because of the magnitude of his service to them, to accord to him immortality."

The Christian apologist Firmicus Maternus gives a rationalized euhemeristic account of the myth whereby Liber (Dionysus) was the bastard son of a Cretan king named Jupiter (Zeus). [68] When Jupiter left his kingdom in the boy's charge, the king's jealous wife Juno (Hera), conspired with her servants, the Titans, to murder the bastard child. Beguiling him with toys, the Titans ambushed and killed the boy. To dispose of the evidence of their crime, the Titans chopped the body into pieces, cooked, and ate them. However the boy's sister Minerva (Athena), who had been part of the murder plot, kept the heart. When her father the king returned, the sister turned informer and gave the boy's heart to the king. [69] In his fury, the king tortured and killed the Titans, and in his grief, he had a statue of the boy made, which contained the boy's heart in its chest, and a temple erected in the boy's honour. [70] The Cretans, in order to pacify their furious savage and despotic king, established the anniversary of the boy's death as a holy day. Sacred rites were held, in which the celebrants howling and feigning insanity tore to pieces a live bull with their teeth, and the basket in which boy's heart had been saved, was paraded to the blaring of flutes and the crashing of cymbals, thereby turning a mere boy into a god. [71]

The anthropogony

Most sources make no mention of what happened to the Titans after the murder of Dionysus. In the standard account of the Titans, given in Hesiod's Theogony (which does not mention Dionysus), after being overthrown by Zeus and the other Olympian gods, in the ten-year-long Titanomachy, the Titans are imprisoned in Tartarus. [72] This might seem to preclude any subsequent story of the Titans killing Dionysus, [73] and perhaps in an attempt to reconcile this standard account with the Dionysus Zagreus myth, according to Arnobius and Nonnus, the Titans end up imprisoned by Zeus in Tartarus, as punishment for their murder of Dionysus. [74]

However, according to one source, from the fate of the Titans came a momentous event, the birth of humankind. Commonly presented as a part of the myth of the dismembered Dionysus Zagreus, is an Orphic anthropogony, that is, an Orphic account of the origin of human beings. According to this widely held view, as punishment for the crime of the sparagmos, Zeus struck the Titans with his thunderbolt, and from the remains of the destroyed Titans humankind was born, which resulted in a human inheritance of ancestral guilt, for this original sin of the Titans, and by some accounts "formed the basis for an Orphic doctrine of the divinity of man." [75] However, when and to what extent there existed any Orphic tradition which included these elements is the subject of open debate. [76]

The only ancient source to explicitly connect the sparagmos and the anthropogony is the 6th century AD Neoplatonist Olympiodorus, who, as part of an argument against committing suicide, states that to take one's life is "forbidden" because human bodies have a divine Dionysiac element within them. He explains that, in the Orphic tradition, after the Titans dismember and eat Dionysus, Zeus, out of anger, "strikes them with his thunderbolts, and the soot of the vapors that rise from them becomes the matter from which men are created", meaning that, because the Titans ate the flesh of Dionysus, humans are a part of Dionysus, and so suicide is "forbidden because our bodies belong to Dionysus". [77]

The 2nd century AD biographer and essayist Plutarch, does make a connection between the sparagmos and a subsequent punishment of the Titans, but makes no mention of the anthropogony, or Orpheus, or Orphism. In his essay On the Eating of Flesh, Plutarch writes of "stories told about the sufferings and dismemberment of Dionysus and the outrageous assaults of the Titans upon him, and their punishment and blasting by thunderbolt after they had tasted his blood". [78]

Other sources have been taken as evidence for the anthropogony having been part of the story before Olympiodorus. [79] The 5th-century AD Neoplatonist Proclus writes that, according to Orpheus, there were three races of humans, the last of which is the "Titanic race", which "Zeus formed [συστήσασθα] from the limbs of the Titans". [80] Proclus also refers to the "mythical chastisement of the Titans and the generation of all mortal living beings out of them" told by Orpheus, [81] connecting the birth of mankind with the punishment of the Titans, though it is unclear whether this punishment comes after the dismemberment of Dionysus or the Hesiodic Titanomachy. [82] Damascius, after mentioning the Titans' "plot against Dionysus", [83] recounts that "lightning-bolts, shackles, [and] descents into various lower regions" are the three punishments which it has been said the Titans suffered, [84] and then states that humans are "created from the fragments of the Titans", and "their dead bodies" have "become men themselves". [85] Passages from earlier sources have also been interpreted as referring to this idea: the 1st century AD writer Dio Chrysostom writes that humans are "of the blood of the Titans", [86] while the Orphic Hymns call the Titans the "ancestors of our fathers". [87]

Earlier allusions to the myth possibly occur in the works of the poet Pindar, Plato, and Plato's student Xenocrates. A fragment from a poem, presumed to be by Pindar, mentions Persephone accepting "requital for ancient wrong", from the dead, which might be a reference to humans' inherited responsibility for the Titans' killing of Dionysus. [88] Plato, in presenting a succession of stages whereby, because of excessive liberty, men degenerate from reverence for the law, to lawlessness, describes the last stage where "men display and reproduce the character of the Titans of story". [89] This Platonic passage is often taken as referring to the anthropogony, however, whether men are supposed by Plato to "display and reproduce" this lawless character because of their Titanic heritage, or by simple imitation, is unclear. [90] Xenocrates' reference to the Titans (and perhaps Dionysus) to explain Plato's use of the word "custody" (φρούρα), has also been seen as possible evidence of a pre-Hellenistic date for the myth. [91]