Related Research Articles

In computing, BIOS is firmware used to provide runtime services for operating systems and programs and to perform hardware initialization during the booting process. The BIOS firmware comes pre-installed on an IBM PC or IBM PC compatible's system board and exists in some UEFI-based systems to maintain compatibility with operating systems that do not support UEFI native operation. The name originates from the Basic Input/Output System used in the CP/M operating system in 1975. The BIOS originally proprietary to the IBM PC has been reverse engineered by some companies looking to create compatible systems. The interface of that original system serves as a de facto standard.

The IBM Personal Computer is the first microcomputer released in the IBM PC model line and the basis for the IBM PC compatible de facto standard. Released on August 12, 1981, it was created by a team of engineers and designers at International Business Machines (IBM), directed by William C. Lowe and Philip Don Estridge in Boca Raton, Florida.

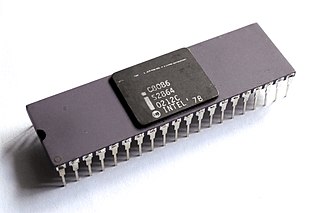

The 8086 is a 16-bit microprocessor chip designed by Intel between early 1976 and June 8, 1978, when it was released. The Intel 8088, released July 1, 1979, is a slightly modified chip with an external 8-bit data bus, and is notable as the processor used in the original IBM PC design.

The Intel 486, officially named i486 and also known as 80486, is a microprocessor. It is a higher-performance follow-up to the Intel 386. The i486 was introduced in 1989. It represents the fourth generation of binary compatible CPUs following the 8086 of 1978, the Intel 80286 of 1982, and 1985's i386.

IBM PC compatible computers are technically similar to the original IBM PC, XT, and AT, all from computer giant IBM, that are able to use the same software and expansion cards. Such computers were referred to as PC clones, IBM clones or IBM PC clones. The term "IBM PC compatible" is now a historical description only, since IBM no longer sells personal computers after it sold its personal computer division in 2005 to Chinese technology company Lenovo. The designation "PC", as used in much of personal computer history, has not meant "personal computer" generally, but rather an x86 computer capable of running the same software that a contemporary IBM PC could. The term was initially in contrast to the variety of home computer systems available in the early 1980s, such as the Apple II, TRS-80, and Commodore 64. Later, the term was primarily used in contrast to Apple's Macintosh computers.

Wintel is the partnership of Microsoft Windows and Intel producing personal computers using Intel x86-compatible processors running Microsoft Windows.

A Chinese wall or ethical wall is an information barrier protocol within an organization designed to prevent exchange of information or communication that could lead to conflicts of interest. For example, a Chinese wall may be established to separate people who make investments from those who are privy to confidential information that could improperly influence the investment decisions. Firms are generally required by law to safeguard insider information and ensure that improper trading does not occur.

The NEC V20 is a microprocessor that was designed and produced by NEC. It is both pin compatible and object-code compatible with the Intel 8088, with an instruction set architecture (ISA) similar to that of the Intel 80188 with some extensions. The V20 was introduced in March 1984.

In computing, a clone is hardware or software that is designed to function in exactly the same way as another system. A specific subset of clones are remakes, which are revivals of old, obsolete, or discontinued products.

Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp., 714 F.2d 1240, was the first time an appellate level court in the United States held that a computer's BIOS could be protected by copyright. As second impact, this ruling clarified that binary code, the machine readable form of software and firmware, was copyrightable too and not only the human-readable source code form of software.

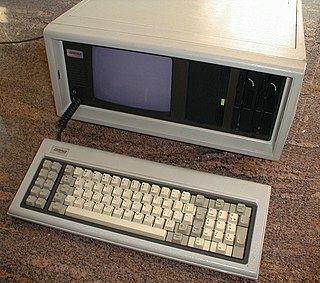

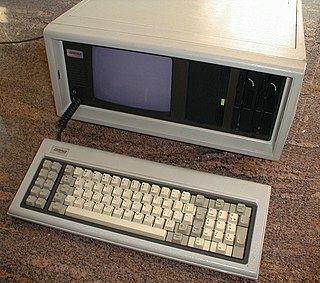

The Compaq Portable is an early portable computer which was one of the first IBM PC compatible systems. It was Compaq Computer Corporation's first product, to be followed by others in the Compaq Portable series and later Compaq Deskpro series. It was not simply an 8088-CPU computer that ran a Microsoft DOS as a PC "work-alike", but contained a reverse-engineered BIOS, and a version of MS-DOS that was so similar to IBM's PC DOS that it ran nearly all its application software. The computer was also an early variation on the idea of an "all-in-one".

A Macintosh clone is a computer running the Mac OS operating system that was not produced by Apple Inc. The earliest Mac clones were based on emulators and reverse-engineered Macintosh ROMs. During Apple's short lived Mac OS 7 licensing program, authorized Mac clone makers were able to either purchase 100% compatible motherboards or build their own hardware using licensed Mac reference designs.

The PC-9800 series, commonly shortened to PC-98 or 98, is a lineup of Japanese 16-bit and 32-bit personal computers manufactured by NEC from 1982 to 2000. The platform established NEC's dominance in the Japanese personal computer market, and, by 1999, more than 18 million units had been sold. While NEC did not market these specific machines in the West, it sold the NEC APC series, which had similar hardware to early PC-98 models.

Phoenix Technologies Ltd. is an American company that designs, develops and supports core system software for personal computers and other computing devices. The company's products – commonly referred to as BIOS or firmware – support and enable the compatibility, connectivity, security and management of the various components and technologies used in such devices. Phoenix Technologies and IBM developed the El Torito standard.

The Compaq Deskpro is a line of business-oriented desktop computers manufactured by Compaq, then replaced by the Evo brand in 2001. Models were produced containing microprocessors from the 8086 up to the x86-based Intel Pentium 4.

Following the introduction of the IBM Personal Computer, or IBM PC, many other personal computer architectures became extinct within just a few years. It led to a wave of IBM PC compatible systems being released.

A video game console emulator is a type of emulator that allows a computing device to emulate a video game console's hardware and play its games on the emulating platform. More often than not, emulators carry additional features that surpass limitations of the original hardware, such as broader controller compatibility, timescale control, easier access to memory modifications, and unlocking of gameplay features. Emulators are also a useful tool in the development process of homebrew demos and the creation of new games for older, discontinued, or rare consoles.

Corona Data Systems, later renamed Cordata, was an American personal computer company. It was one of the earliest IBM PC compatible computer system companies. Manufacturing was primarily done by Daewoo of Korea, which became a major investor in the company and ultimately the owner.

Sony Computer Entertainment v. Connectix Corporation, 203 F.3d 596 (2000), commonly referred to as simply Sony v. Connectix, is a decision by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which ruled that the copying of a copyrighted BIOS software during the development of an emulator software does not constitute copyright infringement, but is covered by fair use. The court also ruled that Sony's PlayStation trademark had not been tarnished by Connectix Corp.'s sale of its emulator software, the Virtual Game Station.

Structure, sequence and organization (SSO) is a term used in the United States to define a basis for comparing one software work to another in order to determine if copying has occurred that infringes on copyright, even when the second work is not a literal copy of the first. The term was introduced in the case of Whelan v. Jaslow in 1986. The method of comparing the SSO of two software products has since evolved in attempts to avoid the extremes of over-protection and under-protection, both of which are considered to discourage innovation. More recently, the concept has been used in Oracle America, Inc. v. Google, Inc.

References

- ↑ Schwartz, Mathew (2001-11-12). "Reverse-Engineering". computerworld.com. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

To protect against charges of having simply (and illegally) copied IBM's BIOS, Phoenix reverse-engineered it using what's called a "clean room," or "Chinese wall," approach. First, a team of engineers studied the IBM BIOS—about 8KB of code—and described everything it did as completely as possible without using or referencing any actual code. Then Phoenix brought in a second team of programmers who had no prior knowledge of the IBM BIOS and had never seen its code. Working only from the first team's functional specifications, the second team wrote a new BIOS that operated as specified.

- ↑ Bernard A. Galler (1995). Software and Intellectual Property Protection: Copyright and Patent Issues for Computer and Legal Professionals. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-89930-974-3.

- ↑ Caruso, Denise (February 27, 1984), "IBM Wins Disputes Over PC Copyrights", InfoWorld, p. 15, retrieved February 28, 2011

- ↑ Sanger, David E. (9 June 1984). "EAGLE'S BATTLE FOR SURVIVAL". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Phoenix Says Its BIOS May Foil IBM's Lawsuits". PC Magazine: The Independent Guide to IBM-Standard Personal Computing. Ziff Davis, Inc.: 56 10 July 1984. ISSN 0888-8507.

- ↑ "Matsushita, IBM settle BIOS copyright infringement dispute". Computerworld: The Newspaper for IT Leaders. Computerworld: 67. 2 March 1987. ISSN 0010-4841.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (2 February 1993). "COMPANY NEWS; Japanese Company Is Sued By I.B.M. Over Copyrights". The New York Times.

- ↑ Joseph W. S. Davis; Hiroshi Oda; Yoshikazu Takaishi (1996). Dispute resolution in Japan. Kluwer Law International. pp. 248–254. ISBN 978-90-411-0974-3.

- ↑ "A brief recap of the lawsuit". coolcopyright.com. Archived from the original on 2008-07-03. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ↑ "IMPACT OF APPLE VS. FRANKLIN DECISION By Rob Hassett". internetlegal.com. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ↑ "Refusal of Apple's injunction request". The New York Times. 4 August 1982. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ↑ "The Making of a Computer by Perry Greenberg" (PDF). classiccmp.org. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ↑ "A dumb hypothetical about the legality of someone documenting Windows XP - ReactOS Forum".

- 1 2 "Coherent sources released under a 3-clause BSD license – Virtually Fun". virtuallyfun.com. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ↑ Dennis Ritchie (April 10, 1998). "Re: Coherent". Newsgroup: alt.folklore.computers. Usenet: 352DC4B7.3030@bell-labs.com.

- ↑ Jorge Contreras, Laura Handley, and Terrence Yang, "NEC v. Intel: Breaking New Ground in the Law of Copyright, Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, Volume 3, Spring Issue, 1990, pp. 209–222 (particularly p. 213)

- ↑ David S. Elkins, “NEC v. Intel: A Guide to Using "Clean Room" Procedures as Evidence”, Computer Law Journal, vol. 4, issue 10, (Winter 1990) pp. 453–481

- ↑ Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc. v. Connectix Corporation , 203F.3d596 (9th Cir.2000).

- ↑ Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc. v. Connectix Corporation , 203 F.3d 596 (9th Cir. 2000). Web Archive.org copy, Feb 28, 2007.

- ↑ Aboard the Columbia, By Bill Machrone, Page 451, Jun 1983, PC Mag

- ↑ "Price Cut Pressure on Compatible Makers". InfoWorld: 49. 16 July 1984. ISSN 0199-6649.