During the thirteenth century, Mosul, Iraq became home to a school of luxury metalwork which rose to international renown. Artifacts classified as Mosul are some of the most intricately designed and revered pieces of the Middle Ages. [3]

During the thirteenth century, Mosul, Iraq became home to a school of luxury metalwork which rose to international renown. Artifacts classified as Mosul are some of the most intricately designed and revered pieces of the Middle Ages. [3]

The school of metalwork in Mosul is believed to have been founded in the early 13th century under Zengid patronage. During this time, the Zengid region was operating as a vassal under the Ayyubid Sultanate. Control over Mosul as a city central to trade between China, the Mediterranean, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia was contested between the Zengids and the Ayyubid sultan, Saladin, throughout the early acquisitions of the Ayyubid Sultanate in Syria and Iraq after the decline of Fatimid rule. [5] However, the Zengids remained in Mosul and were allowed some degree of authority under the Sultanate.

Around 1256, the Mongol occupation of Iraq began, and the region became a part of the Ilkhanate. [6] Of the artifacts agreed to be "nabish al-Mawsili" (of Mosul), approximately 80% were produced after the commencement of Mongol rule in Mosul. [7] However, it is unclear as to whether or not all of these artifacts were produced within Mosul and later exported as esteemed gifts, or created elsewhere by Mosulian artisans who relocated but maintained the "al-Mawsili" signature.

The process of creating these luxuriously inlaid objects is somewhat complicated and has multiple stages. First, designs are formed on the surface of the metal (usually copper or brass) by relief, piercing, engraving, or chasing. Color is then added to the crevices of the surface by encrustation, overlay or, most commonly, inlay of precious metals. These metal inlays could be sheets or wires hammered into place. The area around the inlaid design was often roughened or covered with some sort of black material. Each craftsman in the industry had their own personal specialization. This specialization could be in a particular metal, technique, object, or step in the process. [8] There are two reasons the casting step of the process usually took place in an urban workshop. The first is simply because most patrons were located in these urban areas. The second is because it would be too difficult to move all of the heavy equipment necessary for casting from one rural location to the next. Inlayers and precious metalworkers were able to travel with ease and were not confined to the workshops as casters were. [8] There were three main inlay innovations that are believed to have originated in Mosul in the thirteenth century- gold inlays, black inlay, and background scrolls inlaid with silver. [9]

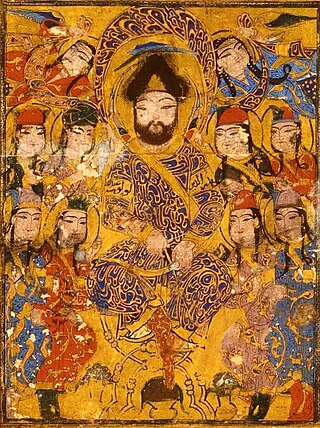

The designs themselves are quite varied in subject matter. Some of the popular motifs include: astrology, hunting, enthronements, battles, court life, and genre scenes. Genre scenes, images of everyday life are particularly prominent. [8] Among the original design traditions there is evidence that can trace them to East Asia through the designs within textiles. Mosul was a great textile industry during the same period that they were producing these inlaid objects and they happened to specialize in reproductions of Chinese silks. It is speculated that many of the traditional metalwork designs were heavily influenced or even direct copies of these silk reproductions. [9]

Historically, many scholars have argued that the Mongol sack of Mosul led to the demise of the luxury metalworking industry, however modern scholarship and an abundance of evidence disproves this. For example, it is known that Mosul metalworkers received an imperial commission by Il-Khan Abu Sa'id in the last years of the Ilkanate. [9] Not only did Mosul continue to produce elaborate inlaid objects after the Mongol sack, they also altered their traditional stylistic choices to coalesce with Mongol taste. There was a new emphasis on minuscule style, the figures represented reflect the Ilkanhid fashion of the period, and they started to put more emphasis on pattern over figuration. [9]

One of the finest examples of the Mosul school of metalworking is the Blacas Ewer.

Another item tentatively attributed to Mosul is the Courtauld bag, which is thought to be the world's oldest surviving handbag. [10]

The scholarship surrounding Mosul Metalwork has been ongoing for a very long time, since it became the first Islamic objects d'art studied in Europe, due to its early arrival on the continent. The diverse opinions on what constitutes as Mosul Metalwork arise due to the style's dispersion across lands and through the component of signatures which identify creators as "al Mawsili", meaning "of Mosul". Within the section of metalwork with signatures, twenty-seven out of the thirty-five state themselves as "al- Mawsili". Out of those, eight state their provenance through the name of the people for which they were created along with statements declaring their engendering within Mosul. [7] [9] Some notable scholars that have helped shape the basis of this study include: Joseph Toussaint Reinaud, Henri Lavoix, Gaston Migeon, Max Van Berchem, Mehmed Aga-Oglu, David Storm Rice.

In the early years of Mosul Metalwork, around 1828, Joseph Toussaint Reinaud, published a collection that included the first item to clearly state its creation in Mosul, the 'Blacas ewer', an artifact consistently scrutinized by scholars when exploring Mosul style. Then in the 1860s the credibility of Mosul was being questioned by scholars, it was during that century that Henry Lavoix declared that Damascus, Aleppo, Mosul, and Egypt all created inlaid metalwork, but specifically singled out Mosul as a source for a unique style unseen throughout the medium. [7]

A critical point in the scholarship came in the beginning of the 20th, through Gaston Migeon, whose claims over the precedency of Mosul caused objection and an urgency for reliability. [7] Migeon also wrote the first comprehensive article introducing the inlaid Islamic metalwork. In the following years, the fluctuation of precedence of Mosul and the lack of it continued, leading up to David Storm Rice, who released the first series of articles exploring the complexities of multiple objects, a process similar to that of Max Van Brehmen and Mehmed Aga-Oglu, two scholars that impacted the relevance and viability of Mosul Metalwork, some of which included the Blacas Ewer, Louvre basin and the Munich Tray.

Present day, Mosul Metalwork is still elusive, and lacks a sustaining amount of scholarship, but scholars continue to construct a field that utilizes substantiated evidence through designs, inscription, and other items engendered specifically in Mosul around the 13th century. [7] An example of this is represented in an article written by Ruba Kana' An who utilizes its iconography and description to construct the argument stating the Freer Ewer as one of many metalworks constructed in Mosul. [12]

Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide range of lands, periods, and genres, Islamic art is a concept used first by Western art historians in the late 19th century. Public Islamic art is traditionally non-representational, except for the widespread use of plant forms, usually in varieties of the spiralling arabesque. These are often combined with Islamic calligraphy, geometric patterns in styles that are typically found in a wide variety of media, from small objects in ceramic or metalwork to large decorative schemes in tiling on the outside and inside of large buildings, including mosques. Other forms of Islamic art include Islamic miniature painting, artefacts like Islamic glass or pottery, and textile arts, such as carpets and embroidery.

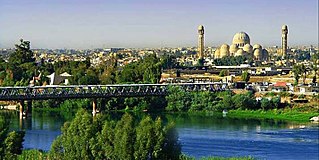

Mosul is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second-largest city in Iraq in terms of population and area after the capital Baghdad. Mosul is approximately 400 km (250 mi) north of Baghdad on the Tigris river. The Mosul metropolitan area has grown from the old city on the western side to encompass substantial areas on both the "Left Bank" and the "Right Bank", as locals call the two riverbanks. Mosul encloses the ruins of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh – once the largest city in the world – on its east side.

The Ayyubid dynasty, also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin had originally served the Zengid ruler Nur ad-Din, leading Nur ad-Din's army in battle against the Crusaders in Fatimid Egypt, where he was made Vizier. Following Nur ad-Din's death, Saladin was proclaimed as the first Sultan of Egypt by the Abbasid Caliphate, and rapidly expanded the new sultanate beyond the frontiers of Egypt to encompass most of the Levant, in addition to Hijaz, Yemen, northern Nubia, Tarabulus, Cyrenaica, southern Anatolia, and northern Iraq, the homeland of his Kurdish family. By virtue of his sultanate including Hijaz, the location of the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina, he was the first ruler to be hailed as the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, a title that would be held by all subsequent sultans of Egypt until the Ottoman conquest of 1517. Saladin's military campaigns in the first decade of his rule, aimed at uniting the various Arab and Muslim states in the region against the Crusaders, set the general borders and sphere of influence of the sultanate of Egypt for the almost three and a half centuries of its existence. Most of the Crusader states, including the Kingdom of Jerusalem, fell to Saladin after his victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. However, the Crusaders reconquered the coast of Palestine in the 1190s.

The Zengid or Zangid dynasty, Atabegs of Mosul was an Atabegate of the Seljuk Empire created in 1127. It formed a Turkoman dynasty of Sunni Muslim faith, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia, and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to Hamadan and from Yemen to Sivas. Imad ad-Din Zengi was the first ruler of the dynasty.

The Bobrinski Bucket, also called the Bobrinski Kettle or Bobrinski Cauldron, is a bronze bucket produced in Herat, present-day Afghanistan in 1163 C.E.. The bucket’s height is a mere 18.5 cm and consists of a rounded body with a rim and heightened base, and a handle in the shape of real and mythological creatures. The bucket is cast in bronze, with copper and silver inlaid decorations and inscriptions throughout the bucket’s handle, rim, and body. The body of the bucket features seven horizontal bands of inlaid decorations, including the rim, consisting of inscription and iconography. Discussion of the purpose of the bucket has sparked speculation among scholars of Islamic Art.

The Artuqid dynasty was established in 1102 as an Anatolian Beylik (Principality) of the Seljuk Empire. It formed a Turkoman dynasty rooted in the Oghuz Döğer tribe, and followed the Sunni Muslim faith. It ruled in eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. The Artuqid dynasty took its name from its founder, Artuk Bey, who was of the Döger branch of the Oghuz Turks and ruled one of the Turkmen beyliks of the Seljuk Empire. Artuk's sons and descendants ruled the three branches in the region: Sökmen's descendants ruled the region around Hasankeyf between 1102 and 1231; Ilghazi's branch ruled from Mardin and Mayyafariqin between 1106 and 1186 and Aleppo from 1117–1128; and the Harput line starting in 1112 under the Sökmen branch, and was independent between 1185 and 1233.

The Ghurid dynasty was a Persianate dynasty of presumably eastern Iranian Tajik origin, which ruled from the 8th-century in the region of Ghor, and became an Empire from 1175 to 1215. The Ghurids were centered in the hills of the Ghor region in the present-day central Afghanistan, where they initially started out as local chiefs. They gradually converted to Sunni Islam after the conquest of Ghor by the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud of Ghazni in 1011. The Ghurids eventually overran the Ghaznavids when Muhammad of Ghor seized Lahore and expelled the Ghaznavids from their last stronghold.

In modern usage, an aquamanile is a ewer or jug-type vessel in the form of one or more animal or human figures. It usually contained water for the washing of hands over a basin, which was part of both upper-class meals and the Christian Eucharist. Historically the term was used for a basin used for priest's ablutions. The water was supplied by a subdeacon, and aquamanile was a symbol of subdeaconate. The term was later transferred onto secular ewers. Most surviving examples are in metal, typically copper alloys, as pottery versions have rarely survived.

The Seljuk Empire, or the GreatSeljuk Empire, was a high medieval, culturally Turco-Persian, Sunni Muslim empire, established and ruled by the Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. The empire spanned a total area of 3.9 million square kilometres from Anatolia and the Levant in the west to the Hindu Kush in the east, and from Central Asia in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south, and it spanned the time period 1037–1308, though Seljuk rule beyond the Anatolian peninsula ended in 1194.

Mu'izz al-Din Mahmud was the Zengid Emir of Jazirat Ibn 'Umar from 1208 to 1250/51. One of the last Zengid rulers, Mahmud succeeded his infamous father, Mu'izz al-Din Sanjar Shah, as the ruler of a minor Zengid principality. Contemporary sources described Mahmud's extreme cruelty but otherwise say very little about his reign. He seems to have successfully navigated a complex political landscape and formed an alliance with Badr al-Din Lu'lu', the ruler of Mosul. After Mahmud's death, Badr al-Din Lu'lu' appears to have had his son killed and annexed Jazirat Ibn 'Umar to his own territory.

Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I was the Zengid Emir of Mosul 1193–1211. He was successor of Izz al-Din Mas'ud. He was appointed by the Ayyubids to this position in 1193. One of his slaves was Badr ad-Din Lu'lu', who became a famous ruler of Mosul, and a prominent patron of the arts.

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, where he governed in variety of capacities from 1234 to 1259 following the death of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud. He was the founder of the short-lived Luluid dynasty. Originally a slave of the Zengid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, he was the first Middle-Eastern mamluk to transcend servitude and become an emir in his own right, founding the dynasty of the Lu'lu'id emirs (1234-1262), and anticipating the rise of the Bahri Mamluks of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt by twenty years. He preserved control of al-Jazira through a series of tactical submissions to larger neighboring powers, at various times recognizing Ayyubid, Rûmi Seljuq, and Mongol overlords. His surrender to the Mongols after 1243 temporarily spared Mosul the destruction experienced by other settlements in Mesopotamia.

Al-Malik al-ʿĀdil Sayf ad-Dīn Abū Bakr ibn Nāṣir ad-Dīn Muḥammad was the Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt from 1238 to 1240.

Nasr ad-Din Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Asad ad-Din Shirkuh was the Kurdish Ayyubid emir of Homs from 1179 to 1186.

Gökböri, or Muzaffar ad-Din Gökböri, was a leading emir and general of Sultan Saladin, and ruler of Erbil. He served both the Zengid and Ayyubid rulers of Syria and Egypt. He played a pivotal role in Saladin's conquest of Northern Syria and the Jazira and later held major commands in a number of battles against the Crusader states and the forces of the Third Crusade. He was known as Manafaradin, a corruption of his principal praise name, to the Franks of the Crusader states.

Persian art or Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences from the art of neighbouring civilizations have been very important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art. This article covers the art of Persia up to 1925, and the end of the Qajar dynasty; for later art see Iranian modern and contemporary art, and for traditional crafts see arts of Iran. Rock art in Iran is its most ancient surviving art. Iranian architecture is covered at that article.

The Palmer Cup is a 1200–1215 CE goblet from northern Syria or Jazira, and an example of early Islamic glass. It is sometimes described as "Ayyubid", since it corresponds to the time when the Ayyubids disputed control of areas of Northern Mesopotamia with the Zengids and Artuqids, but it belongs artistically to the Northern Mesopotamia region, somewhere between northern Syria and the Jazira. It is now in the British Museum, as part of the Waddesdon Bequest (Room 2A ..

Mahmud the Kurd was a 15th-century Kurdish artist, craftsman and designer of the late medieval era.

Aḥmad ibn 'Umar al-Dhakī al-Mawṣilī was a 13th-century metalworker from Mosul, now in Iraq. He is known from three surviving works over a period of about 20 years from 1223 to 1242–43. He operated an atelier (workshop) with his ghulam Abu Bakr Umar ibn Hajji Jaldak. The epithet "al-Dhaki" means "the sagacious".

The Blacas ewer is a brass ewer, inlaid with silver and copper, made by an esteemed man, Shuja' ibn Man'a al-Mawsili in Mosul in April or May 1232. One of the most important and well-known pieces of metalwork from Mosul, it was likely commissioned for Badr al-Din Lu'lu', who was already the de facto ruler of Mosul when the ewer was made and who officially became ruler one year later. Until 1997, the Blacas ewer was the only known piece of metalwork with an inscription explicitly saying it was made in Mosul. Because of this inscription, it forms one of the core items of the contested "Mosul School" of metalwork, since its Mosuli provenance is undisputed.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)