Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals and sometimes non-metals or metalloids. These additions produce a range of alloys some of which are harder than copper alone or have other useful properties, such as strength, ductility, or machinability.

Damascus steel refers to the high carbon crucible steel of the blades of historical swords forged using the wootz process in the Near East, characterized by distinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water, sometimes in a "ladder" or "rose" pattern. "Damascus steel" developed a high reputation for being tough, resistant to shattering, and capable of being honed to a sharp, resilient edge.

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory and progressing to protohistory. In this usage, it is preceded by the Stone Age and Bronze Age. These concepts originated for describing Iron Age Europe and the ancient Near East. In the archaeology of the Americas, a five-period system is conventionally used instead; indigenous cultures there did not develop an iron-smelting economy in the pre-Columbian era, though some did work copper, bronze, unsmelted iron, and iron from East Asian shipwrecks. Indigenous metalworking arrived in Australia with European contact.

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon with improved strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Because of its high tensile strength and low cost, steel is one of the most commonly manufactured materials in the world. Steel is used in buildings, as concrete reinforcing rods, in bridges, infrastructure, tools, ships, trains, cars, bicycles, machines, electrical appliances, furniture, and weapons.

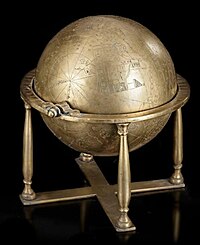

A crucible is a container in which metals or other substances may be melted or subjected to very high temperatures. Although crucibles have historically tended to be made out of clay, they can be made from any material that withstands temperatures high enough to melt or otherwise alter its contents.

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron, cast iron, iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. Crucible steel was first developed in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE in Southern India and Sri Lanka using the wootz process.

Wootz steel is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher-carbon steel, or by ferrite and pearlite banding in lower-carbon steels. It was a pioneering steel alloy developed in southern India in the mid-1st millennium BC and exported globally.

The history of science and technology on the Indian subcontinent begins with the prehistoric human activity of the Indus Valley Civilisation to the early Indian states and empires.

Black and red ware (BRW) is a South Asian earthenware, associated with the neolithic phase, Harappa, Bronze Age India, Iron Age India, the megalithic and the early historical period. Although it is sometimes called an archaeological culture, the spread in space and time and the differences in style and make are such that the ware must have been made by several cultures.

The Painted Grey Ware culture (PGW) is an Iron Age Indo-Aryan culture of the western Gangetic plain and the Ghaggar-Hakra valley in the Indian subcontinent, conventionally dated c.1200 to 600–500 BCE, or from 1300 to 500–300 BCE. It is a successor of the Cemetery H culture and Black and red ware culture (BRW) within this region, and contemporary with the continuation of the BRW culture in the eastern Gangetic plain and Central India.

In the prehistory of the Indian subcontinent, the Iron Age succeeded Bronze Age India and partly corresponds with the megalithic cultures of India. Other Iron Age archaeological cultures of India were the Painted Grey Ware culture and the Northern Black Polished Ware. This corresponds to the transition of the Janapadas or principalities of the Vedic period to the sixteen Mahajanapadas or region-states of the early historic period, culminating in the emergence of the Maurya Empire towards the end of the period.

Metallurgy in China has a long history, with the earliest metal objects in China dating back to around 3,000 BCE. The majority of early metal items found in China come from the North-Western Region. China was the earliest civilization to use the blast furnace and produce cast iron.

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ores began, but by the end of the 2nd millennium BC iron was being produced from iron ores in the region from Greece to India, The use of wrought iron was known by the 1st millennium BC, and its spread defined the Iron Age. During the medieval period, smiths in Europe found a way of producing wrought iron from cast iron, in this context known as pig iron, using finery forges. All these processes required charcoal as fuel.

The metals of antiquity are the seven metals which humans had identified and found use for in prehistoric times in Africa, Europe and throughout Asia: gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, iron, and mercury.

Metals and metal working had been known to the people of modern Italy since the Bronze Age. By 53 BC, Rome had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain, Macedonia, Africa, Asia Minor, Syria and Greece; by the end of the Emperor Trajan's reign, the Roman Empire had grown further to encompass parts of Britain, Egypt, all of modern Germany west of the Rhine, Dacia, Noricum, Judea, Armenia, Illyria, and Thrace. As the empire grew, so did its need for metals.

Sharada SrinivasanFRAS FAAAS is an archaeologist specializing in the scientific study of art, archaeology, archaeometallurgy and culture. She is a professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore, India, and an Honorary University Fellow at the University of Exeter, UK. Srinivasan is also an exponent of classical Bharatanatyam dance. She was awarded India's fourth highest civilian award the Padma Shri in 2019. She is a member of the Calamur family.

Non-ferrous extractive metallurgy is one of the two branches of extractive metallurgy which pertains to the processes of reducing valuable, non-iron metals from ores or raw material. Metals like zinc, copper, lead, aluminium as well as rare and noble metals are of particular interest in this field, while the more common metal, iron, is considered a major impurity. Like ferrous extraction, non-ferrous extraction primarily focuses on the economic optimization of extraction processes in separating qualitatively and quantitatively marketable metals from its impurities (gangue).

The Iron and Steel industry in India is among the most important industries within the country. India surpassed Japan as the second largest steel producer in January 2019. As per worldsteel, India's crude steel production in 2018 was at 106.5 million tonnes (MT), 4.9% increase from 101.5 MT in 2017, which means that India overtook Japan as the world's second largest steel production country. Japan produced 104.3 MT in year 2018, decrease of 0.3% compared to year 2017.