This article reads like a term paper and may require cleanup . Please help to improve this article to make it neutral in tone and meet Wikipedia's quality standards. |

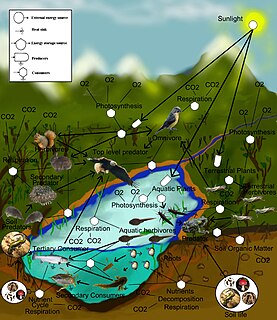

Any action or influence that species have on each other is considered a biological interaction. These interactions between species can be considered in several ways. One such way is to depict interactions in the form of a network, which identifies the members and the patterns that connect them. Species interactions are considered primarily in terms of trophic interactions, which depict which species feed on others.

In biology, a species ( ) is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. Other ways of defining species include their karyotype, DNA sequence, morphology, behaviour or ecological niche. In addition, paleontologists use the concept of the chronospecies since fossil reproduction cannot be examined. While these definitions may seem adequate, when looked at more closely they represent problematic species concepts. For example, the boundaries between closely related species become unclear with hybridisation, in a species complex of hundreds of similar microspecies, and in a ring species. Also, among organisms that reproduce only asexually, the concept of a reproductive species breaks down, and each clone is potentially a microspecies.

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms and ending at apex predator species, detritivores, or decomposer species. A food chain also shows how the organisms are related with each other by the food they eat. Each level of a food chain represents a different trophic level. A food chain differs from a food web, because the complex network of different animals' feeding relations are aggregated and the chain only follows a direct, linear pathway of one animal at a time. Natural interconnections between food chains make it a food web. A common metric used to the quantify food web trophic structure is food chain length. In its simplest form, the length of a chain is the number of links between a trophic consumer and the base of the web and the mean chain length of an entire web is the arithmetic average of the lengths of all chains in a food web.

Contents

- Interaction characteristics

- Importance of interactions

- Keystone species

- Interesting examples

- Criticisms

- References

Currently, ecological networks that integrate non-trophic interactions are being built. The type of interactions they can contain can be classified into six categories: mutualism, commensalism, neutralism, amensalism, antagonism, and competition.

An ecological network is a representation of the biotic interactions in an ecosystem, in which species (nodes) are connected by pairwise interactions (links). These interactions can be trophic or symbiotic. Ecological networks are used to describe and compare the structures of real ecosystems, while network models are used to investigate the effects of network structure on properties such as ecosystem stability.

Mutualism describes the ecological interaction between two or more species where each species benefits. Mutualism is thought to be the most common type of ecological interaction, and it is often dominant in most communities worldwide. Prominent examples include most vascular plants engaged in mutualistic interactions with mycorrhizae, flowering plants being pollinated by animals, vascular plants being dispersed by animals, and corals with zooxanthellae, among many others. Mutualism can be contrasted with interspecific competition, in which each species experiences reduced fitness, and exploitation, or parasitism, in which one species benefits at the "expense" of the other.

Commensalism is a long-term biological interaction (symbiosis) in which members of one species gain benefits while those of the other species neither benefit nor are harmed. This is in contrast with mutualism, in which both organisms benefit from each other, amensalism, where one is harmed while the other is unaffected, and parasitism, where one benefits while the other is harmed. The commensal may obtain nutrients, shelter, support, or locomotion from the host species, which is substantially unaffected. The commensal relation is often between a larger host and a smaller commensal; the host organism is unmodified, whereas the commensal species may show great structural adaptation consonant with its habits, as in the remoras that ride attached to sharks and other fishes. Remoras feed on their hosts' fecal matter, while pilot fish feed on the leftovers of their hosts' meals. Numerous birds perch on bodies of large mammal herbivores or feed on the insects turned up by grazing mammals.

Observing and estimating the fitness costs and benefits of species interactions can be very problematic. The way interactions are interpreted can profoundly affect the ensuing conclusions.

Fitness is the quantitative representation of natural and sexual selection within evolutionary biology. It can be defined either with respect to a genotype or to a phenotype in a given environment. In either case, it describes individual reproductive success and is equal to the average contribution to the gene pool of the next generation that is made by individuals of the specified genotype or phenotype. The fitness of a genotype is manifested through its phenotype, which is also affected by the developmental environment. The fitness of a given phenotype can also be different in different selective environments.