Related Research Articles

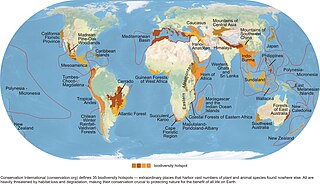

The Holocene extinction, also referred to as the Anthropocene extinction, is an ongoing extinction event caused by human activities during the Holocene epoch. This extinction event spans numerous families of plants and animals, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, impacting both terrestrial and marine species. Widespread degradation of biodiversity hotspots such as coral reefs and rainforests has exacerbated the crisis. Many of these extinctions are undocumented, as the species are often undiscovered before their extinctions.

Biodiversity is the variability of life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distributed evenly on Earth. It is greater in the tropics as a result of the warm climate and high primary productivity in the region near the equator. Tropical forest ecosystems cover less than one-fifth of Earth's terrestrial area and contain about 50% of the world's species. There are latitudinal gradients in species diversity for both marine and terrestrial taxa.

An invasive species is an introduced species that harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native species that become harmful to their native environment after human alterations to its food web. Since the 20th century, invasive species have become serious economic, social, and environmental threats worldwide.

Urban ecology is the scientific study of the relation of living organisms with each other and their surroundings in an urban environment. An urban environment refers to environments dominated by high-density residential and commercial buildings, paved surfaces, and other urban-related factors that create a unique landscape. The goal of urban ecology is to achieve a balance between human culture and the natural environment.

Habitat conservation is a management practice that seeks to conserve, protect and restore habitats and prevent species extinction, fragmentation or reduction in range. It is a priority of many groups that cannot be easily characterized in terms of any one ideology.

Ecosystem diversity deals with the variations in ecosystems within a geographical location and its overall impact on human existence and the environment.

An ecosystem engineer is any species that creates, significantly modifies, maintains or destroys a habitat. These organisms can have a large impact on species richness and landscape-level heterogeneity of an area. As a result, ecosystem engineers are important for maintaining the health and stability of the environment they are living in. Since all organisms impact the environment they live in one way or another, it has been proposed that the term "ecosystem engineers" be used only for keystone species whose behavior very strongly affects other organisms.

Species richness is the number of different species represented in an ecological community, landscape or region. Species richness is simply a count of species, and it does not take into account the abundances of the species or their relative abundance distributions. Species richness is sometimes considered synonymous with species diversity, but the formal metric species diversity takes into account both species richness and species evenness.

Habitat destruction occurs when a natural habitat is no longer able to support its native species. The organisms once living there have either moved to elsewhere or are dead, leading to a decrease in biodiversity and species numbers. Habitat destruction is in fact the leading cause of biodiversity loss and species extinction worldwide.

Ecological restoration, or ecosystem restoration, is the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, destroyed or transformed. It is distinct from conservation in that it attempts to retroactively repair already damaged ecosystems rather than take preventative measures. Ecological restoration can reverse biodiversity loss, combat climate change, support the provision of ecosystem services and support local economies. The United Nations has named 2021-2030 the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

Historical ecology is a research program that focuses on the interactions between humans and their environment over long-term periods of time, typically over the course of centuries. In order to carry out this work, historical ecologists synthesize long-series data collected by practitioners in diverse fields. Rather than concentrating on one specific event, historical ecology aims to study and understand this interaction across both time and space in order to gain a full understanding of its cumulative effects. Through this interplay, humans both adapt to and shape the environment, continuously contributing to landscape transformation. Historical ecologists recognize that humans have had world-wide influences, impact landscape in dissimilar ways which increase or decrease species diversity, and that a holistic perspective is critical to be able to understand that system.

In ecology, a disturbance is a temporary change in environmental conditions that causes a pronounced change in an ecosystem. Disturbances often act quickly and with great effect, to alter the physical structure or arrangement of biotic and abiotic elements. A disturbance can also occur over a long period of time and can impact the biodiversity within an ecosystem.

Freshwater fish are fish species that spend some or all of their lives in bodies of fresh water such as rivers, lakes and inland wetlands, where the salinity is less than 1.05%. These environments differ from marine habitats in many ways, especially the difference in levels of osmolarity. To survive in fresh water, fish need a range of physiological adaptations.

Beddomeia fultoni(B. fultoni) is a species of small freshwater snail belonging to the family Tateidae.

Conservation grazing or targeted grazing is the use of semi-feral or domesticated grazing livestock to maintain and increase the biodiversity of natural or semi-natural grasslands, heathlands, wood pasture, wetlands and many other habitats. Conservation grazing is generally less intensive than practices such as prescribed burning, but still needs to be managed to ensure that overgrazing does not occur. The practice has proven to be beneficial in moderation in restoring and maintaining grassland and heathland ecosystems. Conservation or monitored grazing has been implemented into regenerative agriculture programs to restore soil and overall ecosystem health of current working landscapes. The optimal level of grazing and grazing animal will depend on the goal of conservation. Different levels of grazing, alongside other conservation practices, can be used to induce desired results.

Biodiversity in agriculture is the measure of biodiversity found on agricultural land. Biodiversity is the total diversity of species present in an area at all levels of biological organization. It is characterized by heterogeneous habitats that support the diverse ecological structure. In agricultural areas, biodiversity decreases as varying landscapes are lost and native plants are replaced with cultivated crops. Increasing biodiversity in agriculture can increase the sustainability of farms through the restoration of ecosystem services that aid in regulating agricultural lands. Biodiversity in agriculture can be increased through the process of agroecological restoration, as farm biodiversity is an aspect of agroecology.

This is a list of topics in biodiversity.

Assisted migration is "the intentional establishment of populations or meta-populations beyond the boundary of a species' historic range for the purpose of tracking suitable habitats through a period of changing climate...." It is therefore a nature conservation tactic by which plants or animals are intentionally moved to geographic locations better suited to their present or future habitat needs and climate tolerances — and to which they are unable to migrate or disperse on their own.

Biodiversity loss happens when plant or animal species disappear completely from Earth (extinction) or when there is a decrease or disappearance of species in a specific area. Biodiversity loss means that there is a reduction in biological diversity in a given area. The decrease can be temporary or permanent. It is temporary if the damage that led to the loss is reversible in time, for example through ecological restoration. If this is not possible, then the decrease is permanent. The cause of most of the biodiversity loss is, generally speaking, human activities that push the planetary boundaries too far. These activities include habitat destruction and land use intensification. Further problem areas are air and water pollution, over-exploitation, invasive species and climate change.

Biotic homogenization is the process by which two or more spatially distributed ecological communities become increasingly similar over time. This process may be genetic, taxonomic, or functional, and it leads to a loss of beta (β) diversity. While the term is sometimes used interchangeably with "taxonomic homogenization", "functional homogenization", and "genetic homogenization", biotic homogenization is actually an overarching concept that encompasses the other three. This phenomenon stems primarily from two sources: extinctions of native and invasions of nonnative species. While this process pre-dates human civilization, as evidenced by the fossil record, and still occurs due to natural impacts, it has recently been accelerated due anthropogenic pressures. Biotic homogenization has become recognized as a significant component of the biodiversity crisis, and as such has become of increasing importance to conservation ecologists.

References

- ↑ Luc Hens and Emmanuel K. Boon Causes of Biodiversity Loss: a Human Ecological Analysis, MultiCiencia. Human Ecology Department, Belgium.

- ↑ "Food Security and Biodiversity. Biodiversity in Development" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ↑ Drake, J.A., Mooney, H.A., Castri, F.di., Groves, R.H., Kruger, F.J., Rejmánek, M. and Williamson, M. (1989). Biological Invasions: A Global Perspective, SCOPE 37. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-92085-1

- ↑ Carlton, J (1996). "Pattern, process, and prediction in marine invasion ecology". Biological Conservation. 78 (1–2): 97–106. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(96)00020-1.

- ↑ Cariton, J. T.; Geller, J. B. (1993). "Ecological Roulette: the Global Transport of Nonindigenous Marine Organisms". Science. 261 (5117): 78–82. Bibcode:1993Sci...261...78C. doi:10.1126/science.261.5117.78. PMID 17750551.

- ↑ Lövei, G.L. (1997). "Global Change Through Invasion". Nature. 388 (6643): 627–628. doi: 10.1038/41665 .

- ↑ Rees, P. A. (2001). "Is there a legal obligation to reintroduce animal species into their former habitats?". Oryx. 35 (3): 216–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3008.2001.00178.x .

- ↑ Preston (1962). "The Canonical Distribution of Commonness and Rarity: Part II". Ecology. 43 (3): 410–432. doi:10.2307/1933371. JSTOR 1933371.