Related Research Articles

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthparts adapted to rasping or grinding. Horses and other herbivores have wide flat teeth that are adapted to grinding grass, tree bark, and other tough plant material.

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation and parasitoidism. It is distinct from scavenging on dead prey, though many predators also scavenge; it overlaps with herbivory, as seed predators and destructive frugivores are predators.

The red-backed salamander is a small, hardy woodland salamander species in the family Plethodontidae. The species inhabits wooded slopes in eastern North America, west to Missouri, south to North Carolina, and north from southern Quebec and the Maritime provinces in Canada to Minnesota. It is also known as the redback salamander, eastern red-backed salamander, or the northern red-backed salamander to distinguish it from the southern red-backed salamander. It is one of 56 species in the genus Plethodon. Red-backed salamanders are notable for their color polymorphism and primarily display two color morph varieties, which differ in physiology and anti-predator behavior.

Habitat fragmentation describes the emergence of discontinuities (fragmentation) in an organism's preferred environment (habitat), causing population fragmentation and ecosystem decay. Causes of habitat fragmentation include geological processes that slowly alter the layout of the physical environment, and human activity such as land conversion, which can alter the environment much faster and causes the extinction of many species. More specifically, habitat fragmentation is a process by which large and contiguous habitats get divided into smaller, isolated patches of habitats.

An ecosystem is said to possess ecological stability if it is capable of returning to its equilibrium state after a perturbation or does not experience unexpected large changes in its characteristics across time. Although the terms community stability and ecological stability are sometimes used interchangeably, community stability refers only to the characteristics of communities. It is possible for an ecosystem or a community to be stable in some of their properties and unstable in others. For example, a vegetation community in response to a drought might conserve biomass but lose biodiversity.

Myrmecochory is seed dispersal by ants, an ecologically significant ant-plant interaction with worldwide distribution. Most myrmecochorous plants produce seeds with elaiosomes, a term encompassing various external appendages or "food bodies" rich in lipids, amino acids, or other nutrients that are attractive to ants. The seed with its attached elaiosome is collectively known as a diaspore. Seed dispersal by ants is typically accomplished when foraging workers carry diaspores back to the ant colony, after which the elaiosome is removed or fed directly to ant larvae. Once the elaiosome is consumed, the seed is usually discarded in underground middens or ejected from the nest. Although diaspores are seldom distributed far from the parent plant, myrmecochores also benefit from this predominantly mutualistic interaction through dispersal to favourable locations for germination, as well as escape from seed predation.

Phengaris alcon, the Alcon blue or Alcon large blue, is a butterfly of the family Lycaenidae and is found in Europe and across the Palearctic to Siberia and Mongolia.

Seed predation, often referred to as granivory, is a type of plant-animal interaction in which granivores feed on the seeds of plants as a main or exclusive food source, in many cases leaving the seeds damaged and not viable. Granivores are found across many families of vertebrates as well as invertebrates ; thus, seed predation occurs in virtually all terrestrial ecosystems. Seed predation is commonly divided into two distinctive temporal categories, pre-dispersal and post-dispersal predation, which affect the fitness of the parental plant and the dispersed offspring, respectively. Mitigating pre- and post-dispersal predation may involve different strategies. To counter seed predation, plants have evolved both physical defenses and chemical defenses. However, as plants have evolved seed defenses, seed predators have adapted to plant defenses. Thus, many interesting examples of coevolution arise from this dynamic relationship.

The small tree finch is a species of bird in the Darwin's finch group of the tanager family Thraupidae. It has a grasping beak with curved culmens. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical dry forests and subtropical or tropical dry shrubland. During the non-breeding season it is known to form large groups with small ground-finches.

Mesograzers are defined as small invertebrate herbivores less than 2.5 cm in length, and can include juveniles of some larger species. The feeding behaviour of these small invertebrate herbivores is what classifies them as mesograzers. They are commonly found abundantly on Microalgae, seagrass beds, giant kelp, and coral reefs globally, since these are their main food sources and habitats. Their foraging behaviour is grazing on the organism they are living on, where there are typically masses reaching tens of thousands of mesograzers per meter of habitat. They experience predation from micro-carnivorous fish that help regulate the population of kelp and other common food sources of mesograzers by controlling the population of mesograzers; consequently, grazing is an important process linking aquatic vegetation to higher trophic level. Mesograzers show important top-down effect on marine communities, depending on the diversity and presence of predators. Mesograzers are typically overlooked in scientific research however their foraging effects have been suggested to have extreme effects on the population of their common food sources. They both positively and negatively affect macroalgal performance and productivity through grazing on algal, or through removing epiphytes. Mesograzers typically exist in spaces lacking enemies by inhabiting, therefore consuming, marine vegetation which are defended against more mobile, larger consumers through chemical defenses.

Arctia plantaginis, the wood tiger, is a moth of the family Erebidae. Several subspecies are found in the Holarctic ecozone south to Anatolia, Transcaucasus, northern Iran, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, China, Korea and Japan. One subspecies is endemic to North America.

Hydraulic redistribution is a passive mechanism where water is transported from moist to dry soils via subterranean networks. It occurs in vascular plants that commonly have roots in both wet and dry soils, especially plants with both taproots that grow vertically down to the water table, and lateral roots that sit close to the surface. In the late 1980s, there was a movement to understand the full extent of these subterranean networks. Since then it was found that vascular plants are assisted by fungal networks which grow on the root system to promote water redistribution.

Climax species, also called late seral, late-successional, K-selected or equilibrium species, are plant species that can germinate and grow with limited resources; e.g., they need heat exposure or low water availability. They are the species within forest succession that are more adapted to stable and predictable environments, and will remain essentially unchanged in terms of species composition for as long as a site remains undisturbed.

Melanoplus femurrubrum, the red-legged grasshopper, is a species of grasshopper belonging to the genus Melanoplus. It is one of the most common grasshoppers found in Mexico, the United States, and Canada. This grasshopper is frequently used as a model organism in scientific studies, due to their abundance throughout North America and behavioral response to changes in climate.

Geukensia demissa is a species of mussel, a marine bivalve mollusk in the family Mytilidae, the true mussels. This species is native to the Atlantic coast of North America. The common names for this species include ribbed mussel, Atlantic ribbed marsh mussel and ribbed horsemussel. However, the common name ribbed mussel is also used for the Southern Hemisphere mussel Aulacomya atra. The appearance of the shell is grooved and oval in shape. The interior of this mussel is tinted purple

Ecoimmunology or Ecological Immunology is the study of the causes and consequences of variation in immunity. The field of ecoimmunology seeks to give an ultimate perspective for proximate mechanisms of immunology. This approach places immunology in evolutionary and ecological contexts across all levels of biological organization.

A refuge is a concept in ecology, in which an organism obtains protection from predation by hiding in an area where it is inaccessible or cannot easily be found. Due to population dynamics, when refuges are available, populations of both predators and prey are significantly higher, and significantly more species can be supported in an area.

Carla Cáceres is a professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign known for her research in population, community and evolutionary ecology, focusing on the origins, maintenance, and functional significance of biodiversity within ecosystems. She is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Ecological Society of America, and the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography

Personality in animals has been investigated across a variety of different scientific fields including agricultural science, animal behaviour, anthropology, psychology, veterinary medicine, and zoology. Thus, the definition for animal personality may vary according to the context and scope of study. However, there is recent consensus in the literature for a broad definition that describes animal personality as individual differences in behaviour that are consistent across time and ecological context. Here, consistency refers to the repeatability of behavioural differences between individuals and not a trait that presents itself the same way in varying environments.

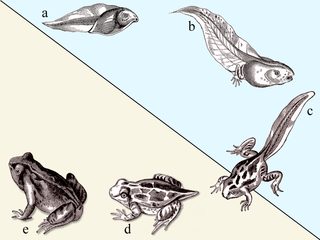

Ontogenetic niche shift is an ecological phenomenon where an organism changes its diet or habitat during its ontogeny (development). During the ontogenetic niche shifting an ecological niche of an individual changes its breadth and position. The best known representatives of taxa that exhibit some kind of the ontogenetic niche shift are fish, insects and amphibians. A niche shift is thought to be determined genetically, while also being irreversible. Important aspect of the ONS is the fact, that individuals of different stages of a population utilize different kind of resources and habitats. The term was introduced in a 1984 paper by biologists Earl E. Werner and James F. Gilliam.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gaillard, J. M.; Coulson, T.; Festa-Bianchet, M. (2008-01-01), "Recruitment", in Jørgensen, Sven Erik; Fath, Brian D. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Ecology, Academic Press, pp. 2982–2986, doi:10.1016/b978-008045405-4.00655-8, ISBN 978-0-08-045405-4 , retrieved 2019-11-25

- 1 2 3 4 Kost, C. (2008-01-01), "Chemical Communication", in Jørgensen, Sven Erik; Fath, Brian D. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Ecology, Academic Press, pp. 557–575, doi:10.1016/b978-008045405-4.00036-7, ISBN 978-0-08-045405-4 , retrieved 2019-11-25

- ↑ Rennert, Robert C; Sorkin, Michael; Garg, Ravi K; Gurtner, Geoffrey C (November 2012). "Stem cell recruitment after injury: lessons for regenerative medicine". Regenerative Medicine. 7 (6): 833–850. doi:10.2217/rme.12.82. ISSN 1746-0751. PMC 3568672 . PMID 23164083.

- 1 2 Matías, Luis; Zamora, Regino; Castro, Jorge (July 2012). "Sporadic rainy events are more critical than increasing of drought intensity for woody species recruitment in a Mediterranean community". Oecologia. 169 (3): 833–844. Bibcode:2012Oecol.169..833M. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-2234-3. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 22218941. S2CID 12463388.

- 1 2 Klopcic, Matija; Poljanec, Ales; Boncina, Andrej (2012-11-15). "Modelling natural recruitment of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)". Forest Ecology and Management. 284: 142–151. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.07.049. ISSN 0378-1127.

- 1 2 Bailey, K. M.; Duffy-Anderson, J. T. (2001-01-01), "Fish Predation and Mortality*", in Steele, John H. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (Second Edition), Academic Press, pp. 417–424, doi:10.1016/b978-012374473-9.00024-2, ISBN 978-0-12-374473-9 , retrieved 2019-11-27

- ↑ Ibáñez, Beatriz; Gómez-Aparicio, Lorena; Stoll, Peter; Ávila, José M.; Pérez-Ramos, Ignacio M.; Marañón, Teodoro (2015-02-23). Carmel, Yohay (ed.). "A Neighborhood Analysis of the Consequences of Quercus suber Decline for Regeneration Dynamics in Mediterranean Forests". PLOS ONE. 10 (2): e0117827. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1017827I. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117827 . ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4338116 . PMID 25706723.

- 1 2 Knights, Antony M.; Firth, Louise B.; Walters, Keith (2012-04-06). "Interactions between Multiple Recruitment Drivers: Post-Settlement Predation Mortality and Flow-Mediated Recruitment". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35096. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735096K. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035096 . ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3320868 . PMID 22493734.

- ↑ Scottish Government, St Andrew's House (2009-12-08). "Fish recruitment". www2.gov.scot. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ Encalada, Andrea C.; Peckarsky, Barbara L. (April 2012). "Large-scale manipulation of mayfly recruitment affects population size". Oecologia. 168 (4): 967–976. Bibcode:2012Oecol.168..967E. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-2147-1. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 22015569. S2CID 14603743.

- ↑ Shertzer, K. W.; Williams, E. H.; Prager, M. H.; Vaughan, D. S. (2014-01-01), "Fishery Models☆", Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences, Elsevier, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-409548-9.09406-9, ISBN 978-0-12-409548-9 , retrieved 2019-11-27

- ↑ Willis, Jay (December 2011). "Modelling swimming aquatic animals in hydrodynamic models". Ecological Modelling. 222 (23–24): 3869–3887. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.10.004.

- ↑ Miller, Thomas J. (2007). "Contribution of individual-based coupled physical–biological models to understanding recruitment in marine fish populations". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 347: 127–138. Bibcode:2007MEPS..347..127M. doi: 10.3354/meps06973 . ISSN 0171-8630. JSTOR 24871559.