Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted orally, music with unknown composers, music that is played on traditional instruments, music about cultural or national identity, music that changes between generations, music associated with a people's folklore, or music performed by custom over a long period of time. It has been contrasted with commercial and classical styles. The term originated in the 19th century, but folk music extends beyond that.

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all human societies. Definitions of music vary widely in substance and approach. While scholars agree that music is defined by a small number of specific elements, there is no consensus as to what these necessary elements are. Music is often characterized as a highly versatile medium for expressing human creativity. Diverse activities are involved in the creation of music, and are often divided into categories of composition, improvisation, and performance. Music may be performed using a wide variety of musical instruments, including the human voice. It can also be composed, sequenced, or otherwise produced to be indirectly played mechanically or electronically, such as via a music box, barrel organ, or digital audio workstation software on a computer.

"World music" is an English phrase for styles of music from non-English speaking countries, including quasi-traditional, intercultural, and traditional music. World music's broad nature and elasticity as a musical category pose obstacles to a universal definition, but its ethic of interest in the culturally exotic is encapsulated in Roots magazine's description of the genre as "local music from out there".

Ethnomusicology is the multidisciplinary study of music in its cultural context, investigating social, cognitive, biological, comparative, and other dimensions involved other than sound. Ethnomusicologists study music as a reflection of culture and investigate the act of musicking through various immersive, observational, and analytical approaches drawn from other disciplines such as anthropology to understand a culture’s music. This discipline emerged from comparative musicology, initially focusing on non-Western music, but later expanded to embrace the study of any and all different kinds of music of the world. Ethnomusicology development resembled that of Anthropology very closely.

The roots of traditional music in Turkey span across centuries to a time when the Seljuk Turks migrated to Anatolia and Persia in the 11th century and contains elements of both Turkic and pre-Turkic influences. Much of its modern popular music can trace its roots to the emergence in the early 1930s drive for Westernization.

The United States' multi-ethnic population is reflected through a diverse array of styles of music. It is a mixture of music influenced by the music of Europe, Indigenous peoples, West Africa, Latin America, Middle East, North Africa, amongst many other places. The country's most internationally renowned genres are traditional pop, jazz, blues, country, bluegrass, rock, rock and roll, R&B, pop, hip-hop/rap, soul, funk, religious, disco, house, techno, ragtime, doo-wop, folk, americana, boogaloo, tejano, surf, and salsa, amongst many others. American music is heard around the world. Since the beginning of the 20th century, some forms of American popular music have gained a near global audience.

Worldbeat is a music genre that blends pop music or rock music with world music or traditional music. Worldbeat is similar to other cross-pollination labels of contemporary and roots genres, and which suggest a rhythmic, harmonic or textural contrast and synthesis between its modern and ethnic elements.

Desi also Deshi, is a loose term used to describe the peoples, cultures, and products of the Indian subcontinent and their diaspora, derived from Sanskrit देश, meaning 'land' or 'country'. Desi traces its origin to the people from the South Asian republics of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, and may also sometimes include people from Afghanistan, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. However, Afghan people are not ethnically Desi.

The Music of Pakistan is a fusion of Turko-Persian, Arab, North Indian, and contemporary Western influences, creating a distinct musical tradition often referred to as "Pakistani Music." The genre has adapted and evolved over time in response to shifting cultural norms and global influences. It has also been deeply shaped by Pakistan's tumultuous political and geopolitical landscape. The Islamization policies of the 1980s, which sought to align Pakistani culture with conservative ideals of Wahhabism, imposed strict censorship on music and musical expression. This period of repression was further fueled by the ongoing Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, during which Wahhabism was aggressively promoted with backing from the United States and Saudi Arabia as part of efforts to counter Soviet influence.

New-age is a genre of music intended to create artistic inspiration, relaxation, and optimism. It is used by listeners for yoga, massage, meditation, and reading as a method of stress management to bring about a state of ecstasy rather than trance, or to create a peaceful atmosphere in homes or other environments. It is sometimes associated with environmentalism and New Age spirituality; however, most of its artists have nothing to do with "New Age spirituality," and some even reject the term.

Balkan music is a type of music found in the Balkan region of southeastern Europe. The music is characterised by complex rhythm. Famous bands in Balkan music include Taraf de Haïdouks, Fanfare Ciocărlia, and No Smoking Orchestra.

Rockism and poptimism are ideological arguments about popular music prevalent in mainstream music journalism. Rockism is the belief that rock music depends on values such as authenticity and artfulness, which elevate it over other forms of popular music. So-called "rockists" may promote the artifices stereotyped in rock music or may regard the genre as the normative state of popular music. Poptimism is the belief that pop music is as worthy of professional critique and interest as rock music. Detractors of poptimism describe it as a counterpart of rockism that unfairly privileges the most famous or best-selling pop, hip hop and R&B acts.

T'ong guitar was a form of Korean music developed in the early 1970s. It was heavily influenced by American pop music, and artists in the genre were considered Korean versions of American folk singers, such as Joan Baez and Bob Dylan.

Americana is an amalgam of American music formed by the confluence of the shared and varied traditions that make up the musical ethos of the United States of America, with particular emphasis on music historically developed in the American South.

Contemporary folk music refers to a wide variety of genres that emerged in the mid-20th century and afterwards which were associated with traditional folk music. Starting in the mid-20th century, a new form of popular folk music evolved from traditional folk music. This process and period is called the (second) folk revival and reached a zenith in the 1960s. The most common name for this new form of music is also "folk music", but is often called "contemporary folk music" or "folk revival music" to make the distinction. The transition was somewhat centered in the United States and is also called the American folk music revival. Fusion genres such as folk rock and others also evolved within this phenomenon. While contemporary folk music is a genre generally distinct from traditional folk music, it often shares the same English name, performers and venues as traditional folk music; even individual songs may be a blend of the two.

Pop music in Ukraine is Western influenced pop music in its various forms that has been growing in popularity in Ukraine since the 1960s.

Popular culture is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a society at a given point in time. Popular culture also encompasses the activities and feelings produced as a result of interaction with these dominant objects. The primary driving forces behind popular culture, especially when speaking of Western popular cultures, are the mass media, mass appeal, marketing and capitalism; and it is produced by what philosopher Theodor Adorno refers to as the "culture industry".

Popular music is music with wide appeal that is typically distributed to large audiences through the music industry. These forms and styles can be enjoyed and performed by people with little or no musical training. As a kind of popular art, it stands in contrast to art music. Art music was historically disseminated through the performances of written music, although since the beginning of the recording industry, it is also disseminated through recordings. Traditional music forms such as early blues songs or hymns were passed along orally, or to smaller, local audiences.

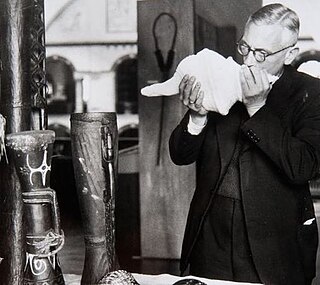

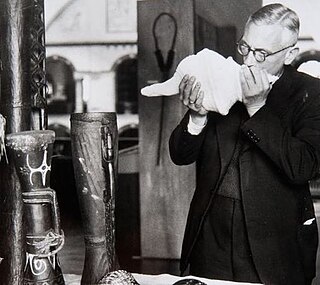

Ethnomusicology is the study of music from the cultural and social aspects of the people who make it. It encompasses distinct theoretical and methodical approaches that emphasize cultural, social, material, cognitive, biological, and other dimensions or contexts of musical behavior, in addition to the sound component. While the traditional subject of musicology has been the history and literature of Western art music, ethnomusicology was developed as the study of all music as a human social and cultural phenomenon. Oskar Kolberg is regarded as one of the earliest European ethnomusicologists as he first began collecting Polish folk songs in 1839. Comparative musicology, the primary precursor to ethnomusicology, emerged in the late 19th century and early 20th century. The International Musical Society in Berlin in 1899 acted as one of the first centers for ethnomusicology. Comparative musicology and early ethnomusicology tended to focus on non-Western music, but in more recent years, the field has expanded to embrace the study of Western music from an ethnographic standpoint.