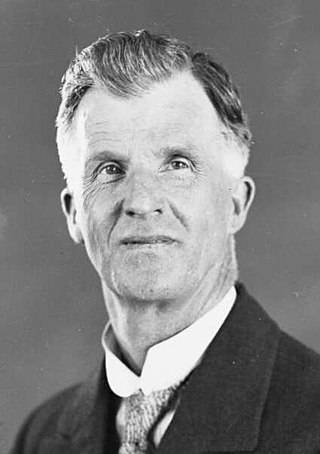

Edward Gough Whitlam was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from December 1972 to November 1975. To date the longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), he was notable for being the head of a reformist and socially progressive government that ended with his controversial dismissal by the then-governor-general of Australia, Sir John Kerr, at the climax of the 1975 constitutional crisis. Whitlam remains the only Australian prime minister to have been removed from office by a governor-general.

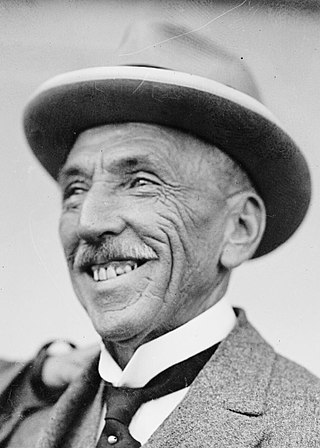

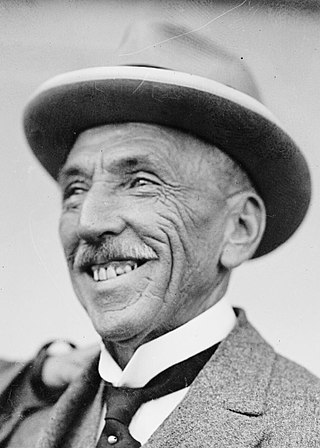

William Morris Hughes was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923. He led the nation during World War I, and his influence on national politics spanned several decades. He was a member of the federal parliament from the Federation of Australia in 1901 until his death in 1952, and is the only person to have served as a parliamentarian for more than 50 years. He represented six political parties during his career, leading five, outlasting four, and being expelled from three.

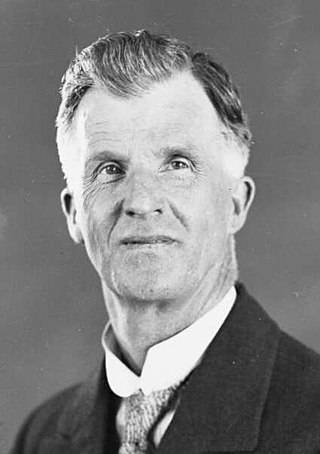

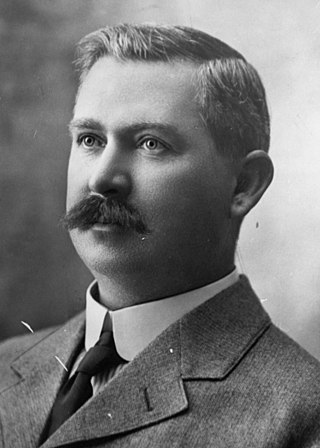

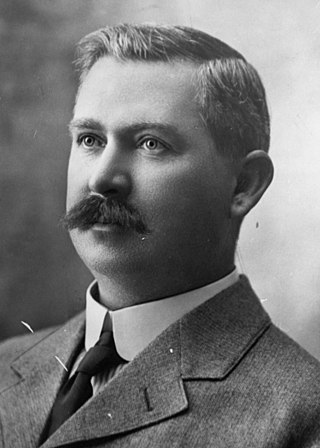

Francis Gwynne Tudor was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1916 until his death. He had previously been a government minister under Andrew Fisher and Billy Hughes.

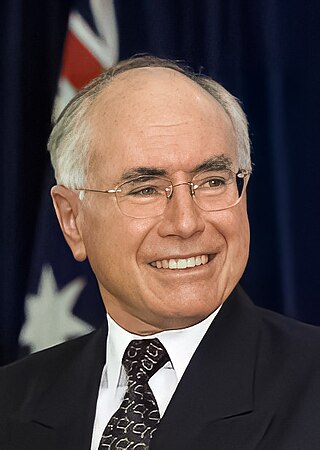

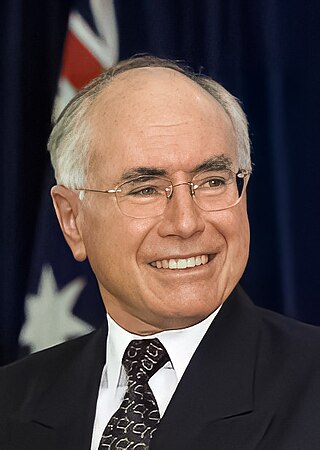

The 2001 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 10 November 2001. All 150 seats in the House of Representatives and 40 seats in the 76-member Senate were up for election. The incumbent Liberal Party of Australia led by Prime Minister of Australia John Howard and coalition partner the National Party of Australia led by John Anderson defeated the opposition Australian Labor Party led by Kim Beazley. As of 2024, this was the most recent election to feature a rematch of both major party leaders. Future Opposition Leader Peter Dutton entered parliament at this election.

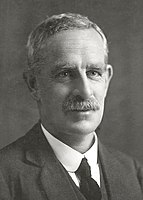

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fusion.

The Liberal–National Coalition, commonly known simply as the Coalition or the LNP, is an alliance of centre-right to right-wing political parties that forms one of the two major groupings in Australian federal politics. The two partners in the Coalition are the Liberal Party of Australia and the National Party of Australia. Its main opponent is the Australian Labor Party (ALP); the two forces are often regarded as operating in a two-party system. The Coalition was last in government from 2013 to 2022. The group is led by Peter Dutton, who succeeded Scott Morrison after the 2022 federal election.

The National Labor Party was formed by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes in 1916, following the 1916 Labor split on the issue of World War I conscription in Australia. Hughes had taken over as leader of the Australian Labor Party and Prime Minister of Australia when anti-conscriptionist Andrew Fisher resigned in 1915. He formed the new party for himself and his followers after he was expelled from the ALP a month after the 1916 plebiscite on conscription in Australia. Hughes held a pro-conscription stance in relation to World War I.

The Australian Party was a political party founded and led by former Australian prime minister Billy Hughes after his expulsion from the Nationalist Party. The party was formed in 1929, and at its peak had five members of federal parliament. It was merged into the new United Australia Party in 1931, having never contested a federal election.

The 1974 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 18 May 1974. All 127 seats in the House of Representatives and all 60 seats in the Senate were up for election, due to a double dissolution. The incumbent Labor Party led by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam defeated the opposition Liberal–Country coalition led by Billy Snedden. This marked the first time that a Labor leader won two consecutive elections.

The 1931 Australian federal election was held on 19 December 1931. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election.

The 1929 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 12 October 1929. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives were up for election, but there was no Senate election. The election was caused by the defeat of the Stanley Bruce-Earle Page Government in the House of Representatives over the Maritime Industries Bill, Bruce having declared that the vote on the bill would constitute a vote of confidence in his government.

The 1925 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 14 November 1925. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and 22 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Nationalist–Country coalition, led by Prime Minister Stanley Bruce, defeated the opposition Labor Party led by Matthew Charlton in a landslide. This was the first time any party had won a fourth consecutive federal election.

The 1922 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 16 December 1922. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Nationalist Party, led by Prime Minister Billy Hughes lost its majority. However, the opposition Labor Party led by Matthew Charlton did not take office as the Nationalists sought a coalition with the fledgling Country Party led by Earle Page. The Country Party made Hughes's resignation the price for joining, and Hughes was replaced as Nationalist leader by Stanley Bruce.

The 1917 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 5 May 1917. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Nationalist Party, led by Prime Minister Billy Hughes, defeated the opposition Labor Party led by Frank Tudor in a landslide.

Walter Leslie Duncan was an Australian politician and trade unionist. He was a Senator for New South Wales from 1920 to 1931.

Thomas Joseph Ryan was an Australian politician who served as Premier of Queensland from 1915 to 1919, as leader of the state Labor Party. He resigned to enter federal politics, sitting in the House of Representatives for the federal Labor Party from 1919 until his premature death less than two years later.

Matthew Charlton was an Australian politician who served as leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and Leader of the Opposition from 1922 to 1928. He led the party to defeat at the 1922 and 1925 federal elections.

The history of the Australian Labor Party has its origins in the Labour parties founded in the 1890s in the Australian colonies prior to federation. Labor tradition ascribes the founding of Queensland Labour to a meeting of striking pastoral workers under a ghost gum tree in Barcaldine, Queensland in 1891. The Balmain, New South Wales branch of the party claims to be the oldest in Australia. Labour as a parliamentary party dates from 1891 in New South Wales and South Australia, 1893 in Queensland, and later in the other colonies.

The Tasmanian Labor Party, officially known as the Australian Labor Party and commonly referred to simply as Tasmanian Labor, is the Tasmanian branch of the Australian Labor Party. It has been one of the most successful state Labor parties in Australia in terms of electoral success.