This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page . (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The phonology of Faroese has an inventory similar to the closely related Icelandic language, but markedly different processes differentiate the two. Similarities include an aspiration contrast in stop consonants, the retention of front rounded vowels and vowel quality changes instead of vowel length distinctions.

Contents

- Vowels

- Monophthongs

- Diphthongs

- Length

- Hiatus phenomena

- Unstressed vowels

- Consonants

- Omissions in consonant clusters

- Phonological history

- Vowel mergers

- Skerping

- Sample

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Lord's Prayer

- Notes

- References

- Bibliography

- Further reading

- External links

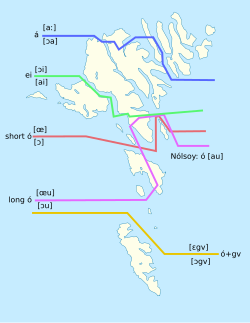

Faroese is not remotely close to having a standard and difference between dialects are very marked. When diving into the specifics, this article primarily discuss Tórshavn varieties, as it is the biggest city on the islands and where most academics have a pied-à-terre.