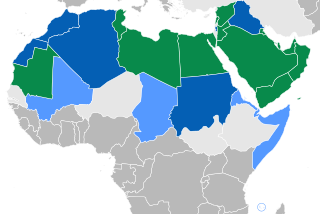

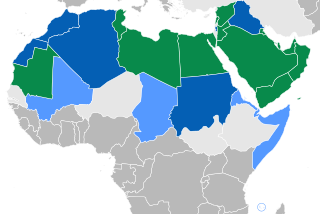

Arabic is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world. Having emerged in the 1st century, it is named after the Arab people; the term "Arab" was initially used to describe those living in the Arabian Peninsula, as perceived by geographers from ancient Greece.

Unless otherwise noted, statements in this article refer to Standard Finnish, which is based on the dialect spoken in the former Häme Province in central south Finland. Standard Finnish is used by professional speakers, such as reporters and news presenters on television.

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. Someone who engages in this study is called a linguist. See also the Outline of linguistics, the List of phonetics topics, the List of linguists, and the List of cognitive science topics. Articles related to linguistics include:

Metathesis is the transposition of sounds or syllables in a word or of words in a sentence. Most commonly, it refers to the interchange of two or more contiguous segments or syllables, known as adjacent metathesis or local metathesis:

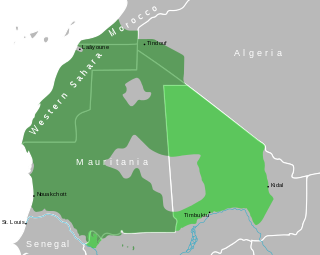

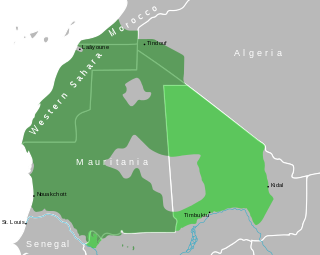

Hassānīya is a variety of Maghrebi Arabic spoken by Mauritanian Arabs and the Sahrawi. It was spoken by the Beni Ḥassān Bedouin tribes, who extended their authority over most of Mauritania and Morocco's southeastern and Western Sahara between the 15th and 17th centuries. Hassānīya Arabic was the language spoken in the pre-modern region around Chinguetti.

While many languages have numerous dialects that differ in phonology, the contemporary spoken Arabic language is more properly described as a continuum of varieties. This article deals primarily with Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), which is the standard variety shared by educated speakers throughout Arabic-speaking regions. MSA is used in writing in formal print media and orally in newscasts, speeches and formal declarations of numerous types.

In phonology, epenthesis means the addition of one or more sounds to a word, especially in the beginning syllable (prothesis) or in the ending syllable (paragoge) or in-between two syllabic sounds in a word. The word epenthesis comes from epi- "in addition to" and en- "in" and thesis "putting". Epenthesis may be divided into two types: excrescence for the addition of a consonant, and for the addition of a vowel, svarabhakti or alternatively anaptyxis. The opposite process, where one or more sounds are removed, is referred to as elision.

Tunisian Arabic, or simply Tunisian, is a set of dialects of Maghrebi Arabic spoken in Tunisia. It is known among its over 11 million speakers as: تونسي, romanized: Tounsi/Tounsiy[ˈtuːnsi](listen), "Tunisian" or Derja "Everyday Language" to distinguish it from Modern Standard Arabic, the official language of Tunisia. Tunisian Arabic is mostly similar to eastern Algerian Arabic and western Libyan Arabic.

Compensatory lengthening in phonology and historical linguistics is the lengthening of a vowel sound that happens upon the loss of a following consonant, usually in the syllable coda, or of a vowel in an adjacent syllable. Lengthening triggered by consonant loss may be considered an extreme form of fusion. Both types may arise from speakers' attempts to preserve a word's moraic count.

In linguistics, assibilation is a sound change resulting in a sibilant consonant. It is a form of spirantization and is commonly the final phase of palatalization.

The Persian language has between six and eight vowels and 26 consonants. It features contrastive stress and syllable-final consonant clusters.

Libyan Arabic is a variety of Arabic spoken mainly in Libya, and neighboring countries. It can be divided into two major dialect areas; the eastern centred in Benghazi and Bayda, and the western centred in Tripoli and Misrata. The Eastern variety extends beyond the borders to the east and share the same dialect with far Western Egypt with between 90,000 and 402,000 speakers in Egypt. A distinctive southern variety, centered on Sabha, also exists and is more akin to the western variety. Another Southern dialect is also shared along the borders with Niger with 12,000 speakers in Niger as of 2019.

The phonology of the Ojibwe language varies from dialect to dialect, but all varieties share common features. Ojibwe is an indigenous language of the Algonquian language family spoken in Canada and the United States in the areas surrounding the Great Lakes, and westward onto the northern plains in both countries, as well as in northeastern Ontario and northwestern Quebec. The article on Ojibwe dialects discusses linguistic variation in more detail, and contains links to separate articles on each dialect. There is no standard language and no dialect that is accepted as representing a standard. Ojibwe words in this article are written in the practical orthography commonly known as the Double vowel system.

In linguistics, synaeresis is a phonological process of sound change in which two adjacent vowels within a word are combined into a single syllable.

The phonology of Turkish deals with current phonology and phonetics, particularly of Istanbul Turkish. A notable feature of the phonology of Turkish is a system of vowel harmony that causes vowels in most words to be either front or back and either rounded or unrounded. Velar stop consonants have palatal allophones before front vowels.

Ottawa is a dialect of the Ojibwe language spoken in a series of communities in southern Ontario and a smaller number of communities in northern Michigan. Ottawa has a phonological inventory of seventeen consonants and seven oral vowels; in addition, there are long nasal vowels the phonological status of which are discussed below. An overview of general Ojibwa phonology and phonetics can be found in the article on Ojibwe phonology. The Ottawa writing system described in Modern orthography is used to write Ottawa words, with transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) used as needed.

In linguistics an accidental gap, also known as a gap, paradigm gap, accidental lexical gap, lexical gap, lacuna, or hole in the pattern, is a potential word, word sense, morpheme, or other form that does not exist in some language despite being theoretically permissible by the grammatical rules of that language. For example, a word pronounced is theoretically possible in English, as it would obey English word-formation rules, but does not currently exist. Its absence is therefore an accidental gap, in the ontologic sense of the word accidental.

This article explains the phonology of Malay and Indonesian based on the pronunciation of Standard Malay, which is the official language of Brunei, Singapore and Malaysia and Indonesian which is the official language of Indonesia and a working language in Timor Leste. Bruneian Standard Malay and Malaysian Standard Malay follow the Johor-Riau Pronunciation, while Singaporean Standard Malay and Indonesian follow the Baku Pronunciation.

This article is about the phonology of Egyptian Arabic, also known as Cairene Arabic or Masri. It deals with the phonology and phonetics of Egyptian Arabic as well as the phonological development of child native speakers of the dialect. To varying degrees, it affects the pronunciation of Literary Arabic by native Egyptian Arabic speakers, as is the case for speakers of all other varieties of Arabic.

The phonological system of the Hejazi Arabic consists of approximately 26 to 28 native consonant phonemes and 8 vowel phonemes:, in addition to 2 diphthongs:. Consonant length and vowel length are both distinctive in Hejazi.