Corpus linguistics is an empirical method for the study of language by way of a text corpus. Corpora are balanced, often stratified collections of authentic, "real world", text of speech or writing that aim to represent a given linguistic variety. Today, corpora are generally machine-readable data collections.

Optical character recognition or optical character reader (OCR) is the electronic or mechanical conversion of images of typed, handwritten or printed text into machine-encoded text, whether from a scanned document, a photo of a document, a scene photo or from subtitle text superimposed on an image.

In linguistics and natural language processing, a corpus or text corpus is a dataset, consisting of natively digital and older, digitalized, language resources, either annotated or unannotated.

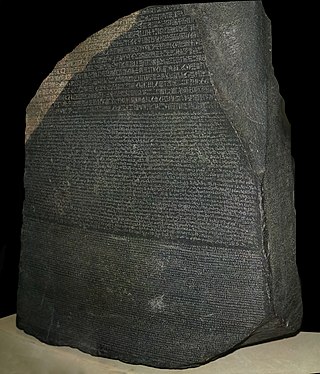

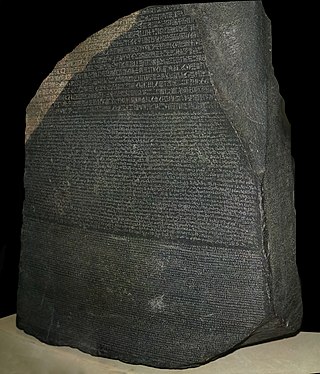

A parallel text is a text placed alongside its translation or translations. Parallel text alignment is the identification of the corresponding sentences in both halves of the parallel text. The Loeb Classical Library and the Clay Sanskrit Library are two examples of dual-language series of texts. Reference Bibles may contain the original languages and a translation, or several translations by themselves, for ease of comparison and study; Origen's Hexapla placed six versions of the Old Testament side by side. A famous example is the Rosetta Stone, whose discovery allowed the Ancient Egyptian language to begin being deciphered.

An n-gram is a sequence of n adjacent symbols in particular order. The symbols may be n adjacent letters, syllables, or rarely whole words found in a language dataset; or adjacent phonemes extracted from a speech-recording dataset, or adjacent base pairs extracted from a genome. They are collected from a text corpus or speech corpus. If Latin numerical prefixes are used, then n-gram of size 1 is called a "unigram", size 2 a "bigram" etc. If, instead of the Latin ones, the English cardinal numbers are furtherly used, then they are called "four-gram", "five-gram", etc. Similarly, using Greek numerical prefixes such as "monomer", "dimer", "trimer", "tetramer", "pentamer", etc., or English cardinal numbers, "one-mer", "two-mer", "three-mer", etc. are used in computational biology, for polymers or oligomers of a known size, called k-mers. When the items are words, n-grams may also be called shingles.

Dale Hollis Hoiberg is a sinologist and has been the editor-in-chief of the Encyclopædia Britannica since 1997. He holds a PhD degree in Chinese literature and began to work for Encyclopædia Britannica as an index editor in 1978. In 2010, Hoiberg co-authored a paper with Harvard researchers Jean-Baptiste Michel and Erez Lieberman Aiden entitled "Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books". The paper was the first to describe the term culturomics.

The American National Corpus (ANC) is a text corpus of American English containing 22 million words of written and spoken data produced since 1990. Currently, the ANC includes a range of genres, including emerging genres such as email, tweets, and web data that are not included in earlier corpora such as the British National Corpus. It is annotated for part of speech and lemma, shallow parse, and named entities.

Google Books is a service from Google that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical character recognition (OCR), and stored in its digital database. Books are provided either by publishers and authors through the Google Books Partner Program, or by Google's library partners through the Library Project. Additionally, Google has partnered with a number of magazine publishers to digitize their archives.

Linguistic categories include

The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) is a one-billion-word corpus of contemporary American English. It was created by Mark Davies, retired professor of corpus linguistics at Brigham Young University (BYU).

Erez Lieberman Aiden is an American research scientist active in multiple fields related to applied mathematics. He is an associate professor at the Baylor College of Medicine, and formerly a fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows and visiting faculty member at Google. He is an adjunct assistant professor of computer science at Rice University. Using mathematical and computational approaches, he has studied evolution in a range of contexts, including that of networks through evolutionary graph theory and languages in the field of culturomics. He has published scientific articles in a variety of disciplines.

Mark E. Davies is an American linguist. He specializes in corpus linguistics and language variation and change. He is the creator of most of the text corpora from English-Corpora.org as well as the Corpus del español and the Corpus do português. He has also created large datasets of word frequency, collocates, and n-grams data, which have been used by many large companies in the fields of technology and also language learning.

Culturomics is a form of computational lexicology that studies human behavior and cultural trends through the quantitative analysis of digitized texts. Researchers data mine large digital archives to investigate cultural phenomena reflected in language and word usage. The term is an American neologism first described in a 2010 Science article called Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books, co-authored by Harvard researchers Jean-Baptiste Michel and Erez Lieberman Aiden.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to natural-language processing:

Computational social science is an interdisciplinary academic sub-field concerned with computational approaches to the social sciences. This means that computers are used to model, simulate, and analyze social phenomena. It has been applied in areas such as computational economics, computational sociology, computational media analysis, cliodynamics, culturomics, nonprofit studies. It focuses on investigating social and behavioral relationships and interactions using data science approaches, network analysis, social simulation and studies using interactive systems.

Sketch Engine is a corpus manager and text analysis software developed by Lexical Computing since 2003. Its purpose is to enable people studying language behaviour to search large text collections according to complex and linguistically motivated queries. Sketch Engine gained its name after one of the key features, word sketches: one-page, automatic, corpus-derived summaries of a word's grammatical and collocational behaviour. Currently, it supports and provides corpora in over 90 languages.

This is a timeline of optical character recognition.

The TenTen Corpus Family (also called TenTen corpora) is a set of comparable web text corpora, i.e. collections of texts that have been crawled from the World Wide Web and processed to match the same standards. These corpora are made available through the Sketch Engine corpus manager. There are TenTen corpora for more than 35 languages. Their target size is 10 billion (1010) words per language, which gave rise to the corpus family's name.

The Czech National Corpus (CNC) is a large electronic corpus of written and spoken Czech language, developed by the Institute of the Czech National Corpus (ICNC) in the Faculty of Arts at Charles University in Prague. The collection is used for teaching and research in corpus linguistics. The ICNC collaborates with over 200 researchers and students, 270 publishers, and other similar research projects.