| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Competences of the European Union . ( Discuss ) Proposed since December 2025. |

In the European Union, the principle of subsidiarity is the principle that decisions are retained by Member States if the intervention of the European Union is not necessary. The European Union should take action collectively only when Member States' individual power is insufficient. The principle of subsidiarity applied to the European Union can be summarised as "Europe where necessary, national where possible". [1] Subsidiarity is balanced by the primacy of European Union law.

Contents

- EU recognition of the principle of subsidiarity

- The principle of subsidiarity in EU governance

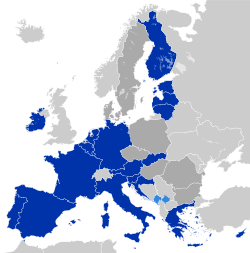

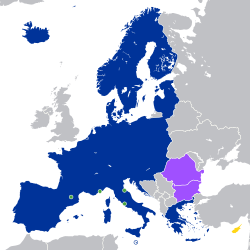

- EU competences

- Federalist v. Intergovernmentalist schools of thought

- The principle of subsidiarity in EU environment policy

- EU environmental policy

- EU ordinary legislative procedure

- European Environment Agency

- References

- External links

The principle of subsidiarity is premised from the fundamental EU principle of conferral, ensuring that the European Union is a union of member states and competences are voluntarily conferred by Member States. The conferral principle also guarantees the principle of proportionality, establishing that the European Union should undertake only the minimum necessary actions.

The principle of subsidiarity is one of the core principles of the European law, [2] and is especially important to the European intergovernmentalist school of thought.