Trout Lake Township is located in north central Minnesota in Itasca County, United States. It is bordered by the City of Coleraine to the west and north, City of Bovey on the north, an unorganized township on the east, and Blackberry Township to the south. Town government was adopted on March 6, 1894. The population was 1,056 at the 2020 census.

Virginia is a city in St. Louis County, Minnesota, United States, on the Mesabi Iron Range. With an economy heavily reliant on large-scale iron ore mining, Virginia is considered the Mesabi Range's commercial center. The population was 8,423 people at the 2020 census. Virginia is a part of the Duluth metropolitan area, and U.S. Highway 53 runs through town.

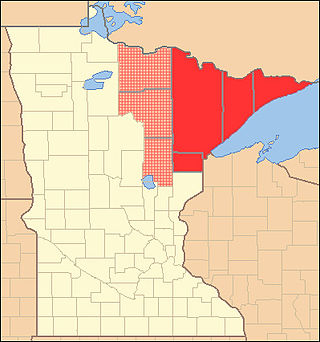

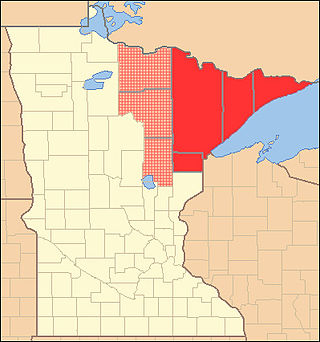

The Mesabi Iron Range is a mining district and mountain range in northeastern Minnesota following an elongate trend containing large deposits of iron ore. It is the largest of four major iron ranges in the region collectively known as the Iron Range of Minnesota. First described in 1866, it is the chief iron ore mining district in the United States. The district is located largely in Itasca and Saint Louis counties. It has been extensively worked since 1892, and has seen a transition from high-grade direct shipping ores through gravity concentrates to the current industry exclusively producing iron ore (taconite) pellets. Production has been dominantly controlled by vertically integrated steelmakers since 1901, and therefore is dictated largely by US ironmaking capacity and demand.

The Iron Range is collectively or individually a number of elongated iron-ore mining districts around Lake Superior in the United States and Canada. Much of the ore-bearing region lies alongside the range of granite hills formed by the Giants Range batholith. These cherty iron ore deposits are Precambrian in the Vermilion Range and middle Precambrian in the Mesabi and Cuyuna ranges, all in Minnesota. The Gogebic Range in Wisconsin and the Marquette Iron Range and Menominee Range in Michigan have similar characteristics and are of similar age. Natural ores and concentrates were produced from 1848 until the mid-1950s, when taconites and jaspers were concentrated and pelletized, and started to become the major source of iron production.

The Arrowhead Region is located in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Minnesota, so called because of its pointed shape. The predominantly rural region encompasses 10,635.26 square miles (27,545.2 km2) of land area and includes Carlton, Cook, Lake and Saint Louis counties. Its population at the 2000 census was 248,425 residents. The region is loosely defined, and Aitkin, Itasca, and Koochiching counties are sometimes considered as part of the region, increasing the land area to 18,221.97 square miles (47,194.7 km2) and the population to 322,073 residents. Primary industries in the region include tourism and iron mining.

The Vermilion Range exists between Tower, Minnesota and Ely, Minnesota, and contains significant deposits of iron ore. Together with the Mesabi, Gunflint, and Cuyuna ranges, these four constitute the Iron Ranges of northern Minnesota. While the Mesabi Range had iron ore close enough to the surface to enable pit mining, mines had to be dug deep underground to reach the ore of the Vermilion and Cuyuna ranges. The Soudan mine was nearly 1/2 mile underground and required blasting of Precambrian sedimentary bedrock.

The Laramie Formation is a geologic formation of the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) age, named by Clarence King in 1876 for exposures in northeastern Colorado, in the United States. It was deposited on a coastal plain and in coastal swamps that flanked the Western Interior Seaway. It contains coal, clay and uranium deposits, as well as plant and animal fossils, including dinosaur remains.

Mountain Iron Mine is a former mine in Mountain Iron, Minnesota, United States. Opened in 1892, it was the first mine on the Mesabi Range, which has proved to be the largest iron ore deposit ever discovered in the United States. Mining operations at the site ceased in 1956. The bottom of the open-pit mine has filled with water but its dimensions are readily visible. The city maintains an overlook in Mountain Iron Locomotive Park.

Manganese is a ghost town and former mining community in the U.S. state of Minnesota that was inhabited between 1912 and 1960. It was built in Crow Wing County on the Cuyuna Iron Range in sections 23 and 28 of Wolford Township, about 2 miles (3 km) north of Trommald, Minnesota. After its formal dissolution, Manganese was absorbed by Wolford Township; the former town site is located between Coles Lake and Flynn Lake. First appearing in the U.S. Census of 1920 with an already dwindling population of 183, the village was abandoned by 1960.

Dinosaur Park is a park located in the 13200 block of Mid-Atlantic Boulevard, near Laurel and Muirkirk, Maryland, and operated by the Prince George's County Department of Parks and Recreation. The park features a fenced area where visitors can join paleontologists and volunteers in searching for early Cretaceous fossils. The park also has an interpretive garden with plants and information signs. The park is in the approximate location of discoveries of Astrodon teeth and bones as early as the 19th century.

The Oliver Iron Mining Company was a mining company operating in Minnesota, United States. It was one of the most prominent companies in the early decades of mining on the Mesabi Range. As a division of U.S. Steel, Oliver dwarfed its competitors—in 1920, it operated 128 mines across the region, while its largest competitor operated only 65.

Paleontology in Maryland refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Maryland. The invertebrate fossils of Maryland are similar to those of neighboring Delaware. For most of the early Paleozoic era, Maryland was covered by a shallow sea, although it was above sea level for portions of the Ordovician and Devonian. The ancient marine life of Maryland included brachiopods and bryozoans while horsetails and scale trees grew on land. By the end of the era, the sea had left the state completely. In the early Mesozoic, Pangaea was splitting up. The same geologic forces that divided the supercontinent formed massive lakes. Dinosaur footprints were preserved along their shores. During the Cretaceous, the state was home to dinosaurs. During the early part of the Cenozoic era, the state was alternatingly submerged by sea water or exposed. During the Ice Age, mastodons lived in the state.

Paleontology in Minnesota refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Minnesota. The geologic record of Minnesota spans from Precambrian to recent with the exceptions of major gaps including the Silurian period, the interval from the Middle to Upper Devonian to the Cretaceous, and the Cenozoic. During the Precambrian, Minnesota was covered by an ocean where local bacteria ended up forming banded iron formations and stromatolites. During the early part of the Paleozoic era southern Minnesota was covered by a shallow tropical sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, massive cephalopods, corals, crinoids, graptolites, and trilobites. The sea withdrew from the state during the Silurian, but returned during the Devonian. However, the rest of the Paleozoic is missing from the local rock record. The Triassic is also missing from the local rock record and Jurassic deposits, while present, lack fossils. Another sea entered the state during the Cretaceous period, this one inhabited by creatures like ammonites and sawfish. Duckbilled dinosaurs roamed the land. The Paleogene and Neogene periods of the ensuing Cenozoic era are also missing from the local rock record, but during the Ice Age evidence points to glacial activity in the state. Woolly mammoths, mastodons, and musk oxen inhabited Minnesota at the time. Local Native Americans interpreted such remains as the bones of the water monster Unktehi. They also told myths about thunder birds that may have been based on Ice Age bird fossils. By the early 19th century, the state's fossil had already attracted the attention of formally trained scientists. Early research included the Cretaceous plant discoveries made by Leo Lesquereux.

Elcor is a ghost town, or more properly, an extinct town, in the U.S. state of Minnesota that was inhabited between 1897 and 1956. It was built on the Mesabi Iron Range near the city of Gilbert in St. Louis County. Elcor was its own unincorporated community before it was abandoned and was never a neighborhood proper of the city of Gilbert. Not rating a figure in the national census, the people of Elcor were only generally considered to be citizens of Gilbert. The area where Elcor was located was annexed by Gilbert when its existing city boundaries were expanded after 1969.

The NorthMet Deposit is a deposit of minerals located in northeastern Minnesota contained within the geological region known as the Duluth Complex. The minerals contained in the deposit include copper, nickel, platinum, silver, palladium, and titanium.

The Coleraine Formation is a geologic formation in Minnesota. It preserves fossils dating back to the Cretaceous period.

Minnesota Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs) are public lands in the state of Minnesota that have been permanently protected to preserve any one or combination of the following:

Thomas Frederick Cole was a mining executive active in Michigan, Minnesota, and Arizona. He was President of the Oliver Iron Mining Company from 1901 to 1909. His namesake boat the SS Thomas F. Cole was built by United States Steel's Pittsburgh Steamship Company in 1907.

Dave Lislegard is an American politician serving in the Minnesota House of Representatives since 2019. A member of the Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party (DFL), Lislegard represents District 7B in northeast Minnesota, which includes the city of Virginia and parts of St. Louis County in the Iron Range.

Paleontology began as a subject of academic interest in Thailand in the early twentieth century, mainly conducted by foreign researchers working with the Royal Department of Mines and Geology, the precursor of the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR). Most early paleontological research was the by-product of mineral exploration for the country's developing mining industry.