The Frisian languages are a closely related group of West Germanic languages, spoken by about 400,000 Frisian people, who live on the southern fringes of the North Sea in the Netherlands and Germany. The Frisian languages are the closest living language group to the Anglic languages; the two groups make up the Anglo-Frisian languages group and together with the Low German dialects these form the North Sea Germanic languages. However, modern English and Frisian are not mutually intelligible, nor are Frisian languages intelligible among themselves, owing to independent linguistic innovations and language contact with neighboring languages.

West Flemish is a collection of Low Franconian varieties spoken in western Belgium and the neighbouring areas of France and the Netherlands.

Holland is a geographical region and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th century, Holland proper was a unified political region within the Holy Roman Empire as a county ruled by the counts of Holland. By the 17th century, the province of Holland had risen to become a maritime and economic power, dominating the other provinces of the newly independent Dutch Republic.

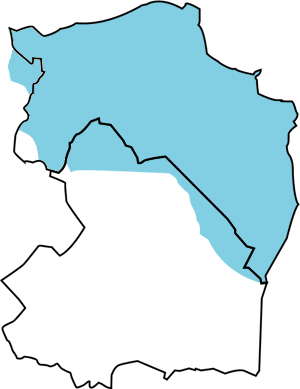

West Frisian, or simply Frisian, is a West Germanic language spoken mostly in the province of Friesland in the north of the Netherlands, mostly by those of Frisian ancestry. It is the most widely spoken of the Frisian languages.

Limburgish refers to a group of South Low Franconian varieties spoken in Belgium and the Netherlands, characterized by their distance to, and limited participation in the formation of, Standard Dutch. In the Dutch province of Limburg, all dialects have been given regional language status, including those comprising ″Limburgish″ as used in this article.

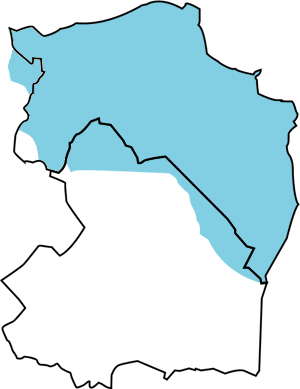

Gronings, is a collective name for some Low Saxon dialects spoken in the province of Groningen and around the Groningen border in Drenthe and Friesland. Gronings and the strongly related varieties in East Frisia have a strong East Frisian influence and take a remarkable position within West Low German. Its typical accent and vocabulary differ strongly from the other Low Saxon dialects.

Hollandic or Hollandish is the most widely spoken dialect of the Dutch language. Hollandic is among the Central Dutch dialects. Other important language varieties of spoken Low Franconian languages are Brabantian, Flemish, Zeelandic, Limburgish and Surinamese Dutch.

Brabantian or Brabantish, also Brabantic or Brabantine, is a dialect group of the Dutch language. It is named after the historical Duchy of Brabant, which corresponded mainly to the Dutch province of North Brabant, the Belgian provinces of Antwerp and Flemish Brabant as well as the Brussels-Capital Region and the province of Walloon Brabant. Brabantian expands into small parts in the west of Limburg, and its strong influence on the Flemish dialects in East Flanders weakens toward the west. In a small area in the northwest of North Brabant (Willemstad), Hollandic is spoken. Conventionally, the Kleverlandish dialects are distinguished from Brabantian, but for no reason other than geography.

East Flemish is a collective term for the two easternmost subdivisions of the so-called Flemish dialects, native to the southwest of the Dutch language area, which also include West Flemish. Their position between West Flemish and Brabantian has caused East Flemish dialects to be grouped with the latter as well. They are spoken mainly in the province of East Flanders and a narrow strip in the southeast of West Flanders in Belgium and eastern Zeelandic Flanders in the Netherlands. Even though the dialects of the Dender area are often discussed together with the East Flemish dialects because of their location, the latter are actually South Brabantian.

Zeelandic is a group of language varieties spoken in the southwestern parts of the Netherlands. It is currently considered a Low Franconian dialect of Dutch, but there have been movements to promote the status of Zeelandic from a dialect of Dutch to a separate regional language, which have been denied by the Dutch Ministry of Internal Affairs. More specifically, it is spoken in the southernmost part of South Holland (Goeree-Overflakkee) and large parts of the province of Zeeland, with the notable exception of eastern Zeelandic Flanders.

Dutch Low Saxon are Low Saxon dialects from the Low German language that are spoken in the northeastern Netherlands and are mostly, but not exclusively, written with local, unstandardised orthographies based on Standard Dutch orthography.

Dutch Renaissance and Golden Age literature is the literature written in the Dutch language between around 1550 and around 1700. This period saw great political and religious changes as the Reformation spread across Northern and Western Europe and the Netherlands fought for independence in the Eighty Years' War.

Dutch is a West Germanic language, that originated from the Old Frankish dialects.

In linguistics, Old Dutch or Old Low Franconian is the set of dialects that evolved from Frankish spoken in the Low Countries during the Early Middle Ages, from around the 6th or 9th to the 12th century. Old Dutch is mostly recorded on fragmentary relics, and words have been reconstructed from Middle Dutch and Old Dutch loanwords in French.

Dutch dialects and varieties are primarily the dialects and varieties that are both cognate with the Dutch language and spoken in the same language area as the Standard Dutch. They are remarkably diverse and are found within Europe mainly in the Netherlands and northern Belgium.

Bible translations into Dutch have a history that goes back to the Middle Ages. The oldest extant Bible translations into the Dutch language date from the Middle Dutch (Diets) period.

Dutch is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken by about 25 million people as a first language and 5 million as a second language and is the third most spoken Germanic language. In Europe, Dutch is the native language of most of the population of the Netherlands and Flanders. Dutch was one of the official languages of South Africa until 1925, when it was replaced by Afrikaans, a separate but partially mutually intelligible daughter language of Dutch. Afrikaans, depending on the definition used, may be considered a sister language, spoken, to some degree, by at least 16 million people, mainly in South Africa and Namibia, and evolving from Cape Dutch dialects.

Maastrichtian or Maastrichtian Limburgish is the dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Dutch city of Maastricht alongside the Dutch language. In terms of speakers, it is the most widespread variant of Limburgish, and it is a tonal one. Like many of the Limburgish dialects spoken in neighbouring Belgian Limburg, Maastrichtian retained many Gallo-Romance influences in its vocabulary.

Flemish is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch, Belgian Dutch, or Southern Dutch. Flemish is native to the region known as Flanders in northern Belgium; it is spoken by Flemings, the dominant ethnic group of the region. Outside of Belgium Flanders, it is also spoken to some extent in French Flanders and the Dutch Zeelandic Flanders.

The Dutch language used in Belgium can also be referred to as Flemish Dutch or Belgian Dutch. Dutch is the mother tongue of about 60% of the population in Belgium, spoken by approximately 6.5 million out of a population of 11 million people. It is the only official language in Flanders, that is to say the provinces of Antwerp, Flemish Brabant, Limburg, East Flanders and West Flanders. Alongside French, it is also an official language of Brussels. However, in the Brussels Capital Region and in the adjacent Flemish-Brabant municipalities, Dutch has been largely displaced by French as an everyday language.