Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock, composed of mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals and tiny fragments of other minerals, especially quartz and calcite. Shale is characterized by breaks along thin laminae or parallel layering or bedding less than one centimeter in thickness, called fissility. It is the most common sedimentary rock.

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of small particles and subsequent cementation of mineral or organic particles on the floor of oceans or other bodies of water at the Earth's surface. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles to settle in place. The particles that form a sedimentary rock are called sediment, and may be composed of geological detritus (minerals) or biological detritus. Before being deposited, the geological detritus was formed by weathering and erosion from the source area, and then transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice, mass movement or glaciers, which are called agents of denudation. Biological detritus was formed by bodies and parts of dead aquatic organisms, as well as their fecal mass, suspended in water and slowly piling up on the floor of water bodies. Sedimentation may also occur as dissolved minerals precipitate from water solution.

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand and silt can be carried in suspension in river water and on reaching the sea bed deposited by sedimentation. If buried, they may eventually become sandstone and siltstone through lithification.

Greywacke or graywacke is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or lithic fragments set in a compact, clay-fine matrix. It is a texturally immature sedimentary rock generally found in Paleozoic strata. The larger grains can be sand- to gravel-sized, and matrix materials generally constitute more than 15% of the rock by volume. The term "greywacke" can be confusing, since it can refer to either the immature aspect of the rock or its fine-grained (clay) component.

The seabed is the bottom of the ocean.

Phosphorite,phosphate rock or rock phosphate is a non-detrital sedimentary rock which contains high amounts of phosphate minerals. The phosphate content of phosphorite (or grade of phosphate rock) varies greatly, from 4% to 20% phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5). Marketed phosphate rock is enriched ("beneficiated") to at least 28%, often more than 30% P2O5. This occurs through washing, screening, de-liming, magnetic separation or flotation. By comparison, the average phosphorus content of sedimentary rocks is less than 0.2%. The phosphate is present as fluorapatite Ca5(PO4)3F typically in cryptocrystalline masses (grain sizes < 1 μm) referred to as collophane-sedimentary apatite deposits of uncertain origin. It is also present as hydroxyapatite Ca5(PO4)3OH or Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, which is often dissolved from vertebrate bones and teeth, whereas fluorapatite can originate from hydrothermal veins. Other sources also include chemically dissolved phosphate minerals from igneous and metamorphic rocks. Phosphorite deposits often occur in extensive layers, which cumulatively cover tens of thousands of square kilometres of the Earth's crust.

Birnessite (Na0.3Ca0.1K0.1)(Mn4+,Mn3+)2O4 · 1.5 H2O is an oxide mineral of manganese along with calcium, potassium and sodium. It has a dark brown to black color with a submetallic luster. It is also very soft, with a Mohs hardness of 1.5. Birnessite is formed by precipitation in lakes, oceans and groundwater and is a major component of desert varnish and deep sea manganese nodules.

Mudrocks are a class of fine grained siliciclastic sedimentary rocks. The varying types of mudrocks include: siltstone, claystone, mudstone, slate, and shale. Most of the particles of which the stone is composed are less than 0.0625 mm and are too small to study readily in the field. At first sight the rock types look quite similar; however, there are important differences in composition and nomenclature. There has been a great deal of disagreement involving the classification of mudrocks. There are a few important hurdles to classification, including:

- Mudrocks are the least understood, and one of the most understudied sedimentary rocks to date

- It is difficult to study mudrock constituents, due to their diminutive size and susceptibility to weathering on outcrops

- And most importantly, there is more than one classification scheme accepted by scientists

In biogeochemistry, remineralization refers to the breakdown or transformation of organic matter into its simplest inorganic forms. These transformations form a crucial link within ecosystems as they are responsible for liberating the energy stored in organic molecules and recycling matter within the system to be reused as nutrients by other organisms.

Biogenic silica (bSi), also referred to as opal, biogenic opal, or amorphous opaline silica, forms one of the most widespread biogenic minerals. For example, microscopic particles of silica called phytoliths can be found in grasses and other plants. Silica is an amorphous metal oxide formed by complex inorganic polymerization processes. This is opposed to the other major biogenic minerals, comprising carbonate and phosphate, which occur in nature as crystalline iono-covalent solids (e.g. salts) whose precipitation is dictated by solubility equilibria. Chemically, bSi is hydrated silica (SiO2·nH2O), which is essential to many plants and animals.

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus, chunks and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks by physical weathering. Geologists use the term clastic with reference to sedimentary rocks as well as to particles in sediment transport whether in suspension or as bed load, and in sediment deposits.

Radiolarite is a siliceous, comparatively hard, fine-grained, chert-like, and homogeneous sedimentary rock that is composed predominantly of the microscopic remains of radiolarians. This term is also used for indurated radiolarian oozes and sometimes as a synonym of radiolarian earth. However, radiolarian earth is typically regarded by Earth scientists to be the unconsolidated equivalent of a radiolarite. A radiolarian chert is well-bedded, microcrystalline radiolarite that has a well-developed siliceous cement or groundmass.

Siliceous ooze is a type of biogenic pelagic sediment located on the deep ocean floor. Siliceous oozes are the least common of the deep sea sediments, and make up approximately 15% of the ocean floor. Oozes are defined as sediments which contain at least 30% skeletal remains of pelagic microorganisms. Siliceous oozes are largely composed of the silica based skeletons of microscopic marine organisms such as diatoms and radiolarians. Other components of siliceous oozes near continental margins may include terrestrially derived silica particles and sponge spicules. Siliceous oozes are composed of skeletons made from opal silica Si(O2), as opposed to calcareous oozes, which are made from skeletons of calcium carbonate organisms (i.e. coccolithophores). Silica (Si) is a bioessential element and is efficiently recycled in the marine environment through the silica cycle. Distance from land masses, water depth and ocean fertility are all factors that affect the opal silica content in seawater and the presence of siliceous oozes.

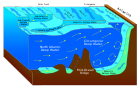

In the deep ocean, marine snow is a continuous shower of mostly organic detritus falling from the upper layers of the water column. It is a significant means of exporting energy from the light-rich photic zone to the aphotic zone below which is referred to as the biological pump. Export production is the amount of organic matter produced in the ocean by primary production that is not recycled (remineralised) before it sinks into the aphotic zone. Because of the role of export production in the ocean's biological pump, it is typically measured in units of carbon .The term was first coined by the explorer William Beebe as he observed it from his bathysphere. As the origin of marine snow lies in activities within the productive photic zone, the prevalence of marine snow changes with seasonal fluctuations in photosynthetic activity and ocean currents. Marine snow can be an important food source for organisms living in the aphotic zone, particularly for organisms which live very deep in the water column.

The Southern Pacific Gyre is part of the Earth’s system of rotating ocean currents, bounded by the Equator to the north, Australia to the west, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to the south, and South America to the east. The center of the South Pacific Gyre is the oceanic pole of inaccessibility, the site on Earth farthest from any continents and productive ocean regions and is regarded as Earth’s largest oceanic desert. The gyre, as with Earth's other four gyres, contains an area with elevated concentrations of pelagic plastics, chemical sludge, and other debris known as the South Pacific garbage patch.

Hemipelagic sediment, or hemipelagite, is a type of marine sediment that consists of clay and silt-sized grains that are terrigenous and some biogenic material derived from the landmass nearest the deposits or from organisms living in the water. Hemipelagic sediments are deposited on continental shelves and continental rises, and differ from pelagic sediment compositionally. Pelagic sediment is composed of primarily biogenic material from organisms living in the water column or on the seafloor and contains little to no terrigenous material. Terrigenous material includes minerals from the lithosphere like feldspar or quartz. Volcanism on land, wind blown sediments as well as particulates discharged from rivers can contribute to Hemipelagic deposits. These deposits can be used to qualify climatic changes and identify changes in sediment provenances.

Reverse weathering generally refers to the formation of a clay neoformation that utilizes cations and alkalinity in a process unrelated to the weathering of silicates. More specifically reverse weathering refers to the formation of authigenic clay minerals from the reaction of 1) biogenic silica with aqueous cations or cation bearing oxides or 2) cation poor precursor clays with dissolved cations or cation bearing oxides.