In Hawaiian religion, Hiʻiaka is a daughter of Haumea and Kāne.

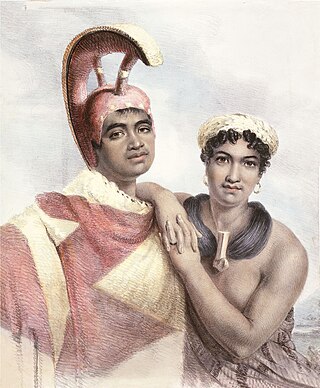

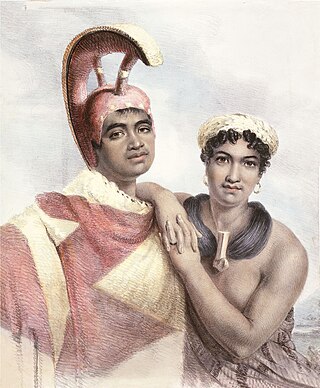

The aliʻi were the traditional nobility of the Hawaiian islands. They were part of a hereditary line of rulers, the noho aliʻi.

Kuini Liliha was a High Chiefess (aliʻi) and noblewoman who served the Kingdom of Hawaii as royal governor of Oʻahu island. She administered the island from 1829 to 1831 following the death of her husband Boki.

The Makahiki season is the ancient Hawaiian New Year festival, in honor of the god Lono of the Hawaiian religion.

Alyxia stellata, known as maile in Hawaiian, is a species of flowering plant in the dogbane family, Apocynaceae, that is native to Hawaii. It grows as either a twining liana, scandent shrub, or small erect shrub, and is one of the few vines that are endemic to the islands. The leaves are usually ternate, sometimes opposite, and can show both types on the same stem. Flowers are quite inconspicuous and have a sweet and light fragrance of honey. The bark is most fragrant and exudes a slightly sticky, milky sap when punctured, characteristic of the family Apocynaceae. The entire plant contains coumarin, a sweet-smelling compound that is also present in vanilla grass, woodruff and mullein. Fruit are oval and dark purple when ripe. Maile is a morphologically variable plant and the Hawaiian names reflect this.

Kalihi is a neighborhood of Honolulu on the island of Oʻahu in Hawaiʻi, United States. Split by Likelike Highway, it is flanked by Liliha, Chinatown, and Downtown Honolulu to the east and Mapunapuna, Moanalua, and Salt Lake to the west.

In Hawaiian mythology, Kapo is a goddess of fertility, sorcery and dark powers. Kapo is also known as Kapo-ʻula-kīnaʻu, where "the epithet ula-kinaʻu is used in allusion to the fact that her attire, red in color, is picked out with black spots. The name Kapo alone is the only by which she is usually known." "Kapo is said to have been born of Papa while she was living up Kalihi valley on Oahu with Wakea, her husband. Some say that she was born from the eyes of Papa. She is of high rank and able to assume many shapes at will." She is the mother of Laka, although some versions have them as the same goddess. She is the sister of Kāne Milohaʻi, Kāmohoaliʻi, Pele, Nāmaka and Hiʻiaka.

Hoʻoponopono is a traditional Hawaiian practice of reconciliation and forgiveness. The Hawaiian word translates into English simply as correction, with the synonyms manage or supervise. Similar forgiveness practices are performed on islands throughout the South Pacific, including Hawaii, Samoa, Tahiti and New Zealand. Traditional hoʻoponopono is practiced by Indigenous Hawaiian healers, often within the extended family by a family member.

Lualualei, Hawaii is the largest coastal valley on the leeward side of Oʻahu in Hawaiʻi. It is located on the west side of the Waianae Range.

A hālau hula is a school or hall in which the Hawaiian dance form called hula is taught. The term comes from hālau, literally, "long house, as for canoes or hula instruction"; "meeting house", and hula, a Polynesian dance form of the Hawaiian Islands. Today, a hālau hula is commonly known as a school or formal institution for hula where the primary responsibility of the people within the hālau is to perpetuate the cultural practice of hula.

Mary Abigail Kawenaʻulaokalaniahiʻiakaikapoliopele Naleilehuaapele Wiggin Pukui, known as Kawena, was a Hawaiian scholar, author, composer, hula expert, and educator.

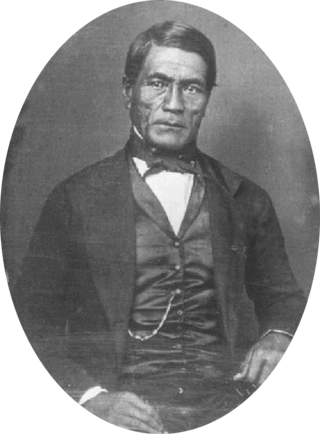

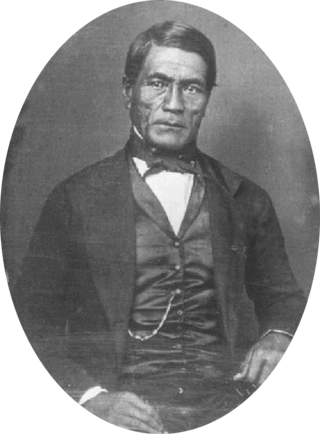

Ioane "John" Kaneiakama Papa ʻĪʻī (1800–1870) was a Hawaiian politician and historian.

Hawaiian religion refers to the indigenous religious beliefs and practices of native Hawaiians, also known as the kapu system. Hawaiian religion is based largely on the tapu religion common in Polynesia and likely originated among the Tahitians and other Pacific islanders who landed in Hawaiʻi between 500 and 1300 AD. It is polytheistic and animistic, with a belief in many deities and spirits, including the belief that spirits are found in non-human beings and objects such as other animals, the waves, and the sky. It was only during the reign of Kamehameha I that a ruler from Hawaii island attempted to impose a singular "Hawaiian" religion on all the Hawaiian islands that was not Christianity.

ʻIolani Luahine, born Harriet Lanihau Makekau, was a native Hawaiian kumu hula, dancer, chanter and teacher, who was considered the high priestess of the ancient hula. The New York Times wrote that she was "regarded as Hawaii's last great exponent of the sacred hula ceremony," and the Honolulu Advertiser wrote: "In her ancient dances, she was the poet of the Hawaiian people." The ʻIolani Luahine Hula Festival was established in her memory, and awards a scholarship award each year to encourage a student to continue the study of hula.

In Hawaiian mythology, Welaʻahilaninui was a god or the first man, the forefather of Hawaiians. He is mentioned as an ancestor of Hawaiian chiefs in the ancient Hawaiian chant Kumulipo.

J. R. Kealoha was a Native Hawaiian and a citizen of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, who became a Union Army soldier during the American Civil War. Considered one of the "Hawaiʻi sons of the Civil War", he was among a group of more than one hundred documented Native Hawaiian and Hawaiʻi-born combatants who fought in the American Civil War while the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was an independent nation.

Microsorum scolopendria, synonym Phymatosorus scolopendria, commonly called monarch fern, musk fern, maile-scented fern, breadfruit fern, or wart fern is a species of fern within the family Polypodiaceae. This fern grows in the wild in the Western Pacific rim from Australia to New Caledonia to Fiji and throughout the South Pacific to French Polynesia.

Keaunui was a High Chief of ʻEwa, Waiʻanae and Waialua in ancient Hawaii. He was a member of the Nanaulu line and is also known as Keaunui-a-Maweke.

Kapaemahu refers to four stones on Waikīkī Beach that were placed there as tribute to four legendary mahu who brought the healing arts from Tahiti to Hawaiʻi centuries ago. It is also the name of the leader of the healers, who according to tradition, transferred their spiritual power to the stones before they vanished. The stones are currently located inside a City and County of Honolulu monument in Honolulu at the western end of Kuhio Beach Park, close to their original home in the section of Waikiki known as Ulukou. Kapaemahu is considered significant as a cultural monument in Waikiki, an example of sacred stones in Hawaiʻi, an insight into indigenous understandings of gender and healing and the subject of an animated film and documentary film.