Related Research Articles

The Ryukyuan people are a Japonic-speaking East Asian ethnic group native to the Ryukyu Islands, which stretch between the islands of Kyushu and Taiwan. Administratively, they live in either Okinawa Prefecture or Kagoshima Prefecture within Japan. They speak one of the Ryukyuan languages, considered to be one of the two branches of the Japonic language family, the other being Japanese and its dialects.

The Okinawan language or Central Okinawan is a Northern Ryukyuan language spoken primarily in the southern half of the island of Okinawa, as well as in the surrounding islands of Kerama, Kumejima, Tonaki, Aguni and a number of smaller peripheral islands. Central Okinawan distinguishes itself from the speech of Northern Okinawa, which is classified independently as the Kunigami language. Both languages are listed by UNESCO as endangered.

The Sakishima Islands are an archipelago located at the southernmost end of the Japanese Archipelago. They are part of the Ryukyu Islands and include the Miyako Islands and the Yaeyama Islands. The islands are administered as part of Okinawa Prefecture, Japan.

Gusuku often refers to castles or fortresses in the Ryukyu Islands that feature stone walls. However, the origin and essence of gusuku remain controversial. In the archaeology of Okinawa Prefecture, the Gusuku period refers to an archaeological epoch of the Okinawa Islands that follows the shell-mound period and precedes the Sanzan period, when most gusuku are thought to have been built. Many gusuku and related cultural remains on Okinawa Island have been listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites under the title Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu.

The Ryukyuan languages, also Lewchewan or Luchuan, are the indigenous languages of the Ryukyu Islands, the southernmost part of the Japanese archipelago. Along with the Japanese language and the Hachijō language, they make up the Japonic language family.

The Ryukyu Kingdom was a kingdom in the Ryukyu Islands from 1429 to 1879. It was ruled as a tributary state of imperial Ming China by the Ryukyuan monarchy, who unified Okinawa Island to end the Sanzan period, and extended the kingdom to the Amami Islands and Sakishima Islands. The Ryukyu Kingdom played a central role in the maritime trade networks of medieval East Asia and Southeast Asia despite its small size. The Ryukyu Kingdom became a vassal state of the Satsuma Domain of Japan after the invasion of Ryukyu in 1609 but retained de jure independence until it was transformed into the Ryukyu Domain by the Empire of Japan in 1872. The Ryukyu Kingdom was formally annexed and dissolved by Japan in 1879 to form Okinawa Prefecture, and the Ryukyuan monarchy was integrated into the new Japanese nobility.

Amami Ōshima, also known as Amami, is the largest island in the Amami archipelago between Kyūshū and Okinawa. It is one of the Satsunan Islands.

The Amami language or languages, also known as Amami Ōshima or simply Ōshima, is a Ryukyuan language spoken in the Amami Islands south of Kyūshū. The southern variety of the Setouchi township may be a distinct language more closely related to Okinawan than it is to northern Ōshima.

The Amami Islands is an archipelago in the Satsunan Islands, which is part of the Ryukyu Islands, and is southwest of Kyushu. Administratively, the group belongs to Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan and the Japan Coast Guard agreed on February 15, 2010, to use the name of Amami-guntō (奄美群島) for the Amami Islands. Prior to that, Amami-shotō (奄美諸島) was also used. The name of Amami is probably cognate with Amamikyu (阿摩美久), the goddess of creation in the Ryukyuan creation myth.

The Ryukyu Islands, also known as the Nansei Islands or the Ryukyu Arc, are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands, with Yonaguni the westernmost. The larger are mostly volcanic islands and the smaller mostly coral. The largest is Okinawa Island.

The invasion of Ryukyu by forces of the Japanese feudal domain of Satsuma took place from March to May of 1609, and marked the beginning of the Ryukyu Kingdom's status as a vassal state under the Satsuma domain. The invasion force was met with stiff resistance from the Ryukyuan military on all but one island during the campaign. Ryukyu would remain a vassal state under Satsuma, alongside its already long-established tributary relationship with China, until it was formally annexed by Japan in 1879 as the Okinawa Prefecture.

Kikaijima is one of the Satsunan Islands, classed with the Amami archipelago between Kyūshū and Okinawa.

Okinawan names today have only two components, the family names first and the given names last. Okinawan family names represent the distinct historical and cultural background of the islands which now comprise Okinawa Prefecture in Japan. Expatriates originally from Okinawa also have these names.

Ryukyuan music, also called Nanto music, is an umbrella term that encompasses diverse musical traditions of the Amami, Okinawa, Miyako and Yaeyama Islands of southwestern Japan. The term of "Southern Islands" is preferred by scholars in this field. The word "Ryūkyū" originally referred to Okinawa Island and has a strong association with the highly centralized Ryukyu Kingdom based on Okinawa Island and its high culture practiced by the samurai class in its capital Shuri. By contrast, scholars who cover a much broader region lay emphasis on folk culture.

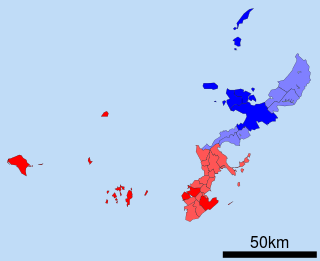

The Northern Ryukyuan languages are a group of languages spoken in the Amami Islands, Kagoshima Prefecture and the Okinawa Islands, Okinawa Prefecture of southwestern Japan. It is one of two primary branches of the Ryukyuan languages, which are then part of the Japonic languages. The subdivisions of Northern Ryukyuan are a matter of scholarly debate.

The Second Shō dynasty was the last dynasty of the Ryukyu Kingdom from 1469 to 1879, ruled by the Second Shō family under the title of King of Chūzan. This family took the family name from the earlier rulers of the kingdom, the first Shō family, even though the new royal family has no blood relation to the previous one. Until the abolition of Japanese peerage in 1947, the head of the family was given the rank of marquess while several cadet branches held the title of baron.

Okinawa (沖縄) is a name with multiple referents. The endonym refers to Okinawa Island in southwestern Japan. Today it can cover some surrounding islands and, more importantly, can refer to Okinawa Prefecture, a much larger administrative division of Japan, although the people from the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands still feel a strong sense of otherness to Okinawa.

Amami Japanese is a variety of the Japanese language spoken on the island of Amami Ōshima. Its native term Ton-futsūgo means "potato standard". Much like Okinawan Japanese, it is a descendant of Standard Japanese but with influences from the traditional Ryukyuan languages.

The Amami reversion movement was a sociopolitical movement that called for the return of the Amami Islands from the U.S. military occupation to Japanese administration. It was mainly led by two groups, (1) the Fukkyō, or Amami Ōshima Nihon Fukki Kyōgikai in the Amami Islands, and (2) the Tokyo-based Amami Rengō, or Zenkoku Amami Rengō Sōhonbu.

Amami-Ōshima Island, Tokunoshima Island, northern part of Okinawa Island, and Iriomote Island (奄美大島、徳之島、沖縄島北部及び西表島) is a serial UNESCO World Heritage Site consisting of five component parts on four Japanese islands in the Ryukyu Chain of the Nansei Islands. The site was selected in terms of biodiversity for having a diverse ecosystem of plant and animal species that are unique to the region.

References

- ↑ Sumita Hiroshi 純田宏 (2005). "Amami guntō no myōji ni tsuite" 奄美群島の名字について. In Amami-gaku kankō iinkai 「奄美学」刊行委員会 (ed.). Amami-gaku奄美学 (in Japanese). Nanpou Shinsha. pp. 351–371.

- ↑ Prior to 1780, gōshi-kaku (郷士格) was known as tojōshujū-kaku (外城衆中格). See (Yuge:2005)

- 1 2 3 4 Yuge Masami 弓削政己 (2005). "Amami no ichiji myōji to gōshikaku ni tsuite" 奄美の一字名字と郷士格について. In Amami-gaku kankō iinkai 「奄美学」刊行委員会 (ed.). Amami-gaku奄美学 (in Japanese). Nanpou Shinsha. pp. 318–350.

- ↑ Yuge Masami 弓削政己 (2004). "Amami kara mita Satsuma to Ryūkyū" 奄美から見た薩摩と琉球. In Kagoshima Junshin Joshi Daigaku Kokusai Bunka Kenkyū Sentā 鹿児島純心女子大学国際文化研究センター (ed.). Shin-Satsuma-gaku 3: Satsuma Amami Ryūkyū新薩摩学3: 薩摩・奄美・琉球 (in Japanese). Nanpou Shinsha. pp. 149–169.

- ↑ "jaanunaa (ヤーヌナー)". Amami Dialect Dictionary. Okinawa Center of Language Study. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "naa (ナー)". Amami Dialect Dictionary. Okinawa Center of Language Study. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "nesena (ネセナ)". Amami Dialect Dictionary. Okinawa Center of Language Study. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "warabïna (ワラブぃナ)". Amami Dialect Dictionary. Okinawa Center of Language Study. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "azana (アザナ)". Amami Dialect Dictionary. Okinawa Center of Language Study. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2011.