Sir Douglas Mawson was a British-born Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Sir Ernest Shackleton, he was a key expedition leader during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 meters long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". Much of an iceberg is below the water's surface, which led to the expression "tip of the iceberg" to illustrate a small part of a larger unseen issue. Icebergs are considered a serious maritime hazard.

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica. It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than 600 kilometres (370 mi) long, and between 15 and 50 metres high above the water surface. Ninety percent of the floating ice, however, is below the water surface.

An ice shelf is a large platform of glacial ice floating on the ocean, fed by one or multiple tributary glaciers. Ice shelves form along coastlines where the ice thickness is insufficient to displace the more dense surrounding ocean water. The boundary between the ice shelf (floating) and grounded ice is referred to as the grounding line; the boundary between the ice shelf and the open ocean is the ice front or calving front.

The Larsen Ice Shelf is a long ice shelf in the northwest part of the Weddell Sea, extending along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula from Cape Longing to Smith Peninsula. It is named after Captain Carl Anton Larsen, the master of the Norwegian whaling vessel Jason, who sailed along the ice front as far as 68°10' South during December 1893. In finer detail, the Larsen Ice Shelf is a series of shelves that occupy distinct embayments along the coast. From north to south, the segments are called Larsen A, Larsen B, and Larsen C by researchers who work in the area. Further south, Larsen D and the much smaller Larsen E, F and G are also named.

The Brunt Ice Shelf borders the Antarctic coast of Coats Land between Dawson-Lambton Glacier and Stancomb-Wills Glacier Tongue. It was named by the UK Antarctic Place-names Committee after David Brunt, British meteorologist, Physical Secretary of the Royal Society, 1948–57, who was responsible for the initiation of the Royal Society Expedition to this ice shelf in 1955.

Iceberg B-15 was the largest recorded iceberg by area. It measured around 295 by 37 kilometres, with a surface area of 11,000 square kilometres, about the size of the island of Jamaica. Calved from the Ross Ice Shelf of Antarctica in March 2000, Iceberg B-15 broke up into smaller icebergs, the largest of which was named Iceberg B-15-A. In 2003, B-15A drifted away from Ross Island into the Ross Sea and headed north, eventually breaking up into several smaller icebergs in October 2005. In 2018, a large piece of the original iceberg was steadily moving northward, located between the Falkland Islands and South Georgia Island. As of August 2023, the U.S. National Ice Center (USNIC) still lists one extant piece of B-15 that meets the minimum threshold for tracking. This iceberg, B-15AB, measures 20 km × 7 km ; it is currently grounded off the coast of Antarctica in the western sector of the Amery region.

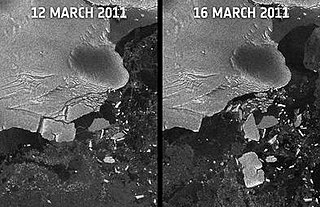

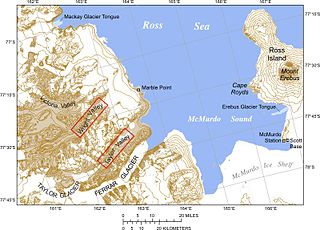

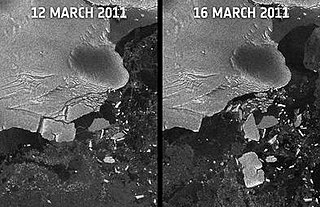

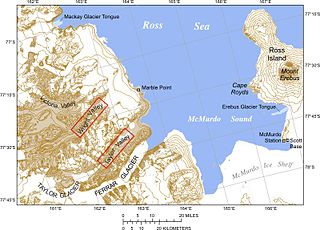

The Drygalski Ice Tongue, Drygalski Barrier, or Drygalski Glacier Tongue is a glacier in Antarctica, on the Scott Coast, in the northern McMurdo Sound of Ross Dependency, 240 kilometres (150 mi) north of Ross Island. The Drygalski Ice Tongue is stable by the standards of Antarctica's icefloes, and stretches 70 kilometres (43 mi) out to sea from the David Glacier, reaching the sea from a valley in the Prince Albert Mountains of Victoria Land. The Drygalski Ice Tongue ranges from 14 to 24 kilometres wide.

Xavier Guillaume Mertz was a Swiss polar explorer, mountaineer, and skier who took part in the Far Eastern Party, a 1912–1913 component of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, which claimed his life. Mertz Glacier on the George V Coast in East Antarctica is named after him.

The Amery Ice Shelf is a broad ice shelf in Antarctica at the head of Prydz Bay between the Lars Christensen Coast and Ingrid Christensen Coast. It is part of Mac. Robertson Land. The name "Cape Amery" was applied to a coastal angle mapped on 11 February 1931 by the British Australian New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) under Douglas Mawson. He named it for William Bankes Amery, a civil servant who represented the United Kingdom government in Australia (1925–28). The Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names interpreted this feature to be a portion of an ice shelf and, in 1947, applied the name Amery to the whole shelf.

Ninnis Glacier is a large, heavily hummocked and crevassed glacier descending steeply from the high interior to the sea in a broad valley, on George V Coast in Antarctica. It was discovered by the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911–14) under Douglas Mawson, who named it for Lieutenant B. E. S. Ninnis, who lost his life on the far east sledge journey of the expedition on 14 December 1912 through falling into the Black Crevasse in the glacier.

Thwaites Glacier is an unusually broad and vast Antarctic glacier located east of Mount Murphy, on the Walgreen Coast of Marie Byrd Land. It was initially sighted by polar researchers in 1940, mapped in 1959–1966 and officially named in 1967, after the late American glaciologist Fredrik T. Thwaites. The glacier flows into Pine Island Bay, part of the Amundsen Sea, at surface speeds which exceed 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) per year near its grounding line. Its fastest-flowing grounded ice is centered between 50 and 100 kilometres east of Mount Murphy. Like many other parts of the cryosphere, it has been adversely affected by climate change, and provides one of the more notable examples of the retreat of glaciers since 1850.

Sulzberger Bay is a bay indenting the front of the Sulzberger Ice Shelf between Fisher Island and Vollmer Island, along the coast of Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica.

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was a 1911–1914 expedition headed by Douglas Mawson that explored the largely uncharted Antarctic coast due south of Australia. Mawson had been inspired to lead his own venture by his experiences on Ernest Shackleton's Nimrod expedition in 1907–1909. During its time in Antarctica, the expedition's sledging parties covered around 4,180 kilometres (2,600 mi) of unexplored territory, while its ship, SY Aurora, navigated 2,900 kilometres (1,800 mi) of unmapped coastline. Scientific activities included meteorological measurements, magnetic observations, an expansive oceanographic program, and the collection of many biological and geological samples, including the discovery of the first meteorite found in Antarctica. The expedition was the first to establish and maintain wireless contact between Antarctica and Australia. Another planned innovation – the use of an aircraft – was thwarted by an accident before the expedition sailed. The plane's fuselage was adapted to form a motorised sledge or "air-tractor", but it proved to be of very limited usefulness.

Iceberg B-9 was an iceberg that calved from Antarctica in 1987. It measured 154 kilometres (96 mi) long and 35 kilometres (22 mi) wide; it had a total area of 5,390 square kilometres (2,080 sq mi), and is one of the longest icebergs ever recorded. This calving took place immediately east of the future calving site of Iceberg B-15; it carried away Little America V which had been closed in December 1959. Starting in October 1987, Iceberg B-9 drifted for 22 months, covering 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) on its journey. Initially, B-9 moved northwest for seven months, before being drawn southward by a subsurface current that eventually led to its colliding with the Ross Ice Shelf in August 1988. It then made a 100-kilometre (62 mi) radius gyre before resuming its northwest drift. It moved at an average speed of 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) per day over the continental shelf, as measured by NOAA-10 and DMSP satellite positions, and by the ARGOS data buoy positions. In early August 1989, B-9 broke into three large pieces north of Cape Adare. These pieces were designated as B-9A, 56 by 35 kilometres, B-9B, 100 by 35 kilometres, and B-9C, 28 by 13 kilometres.

The Erebus Glacier Tongue is a mountain outlet glacier and the seaward extension of Erebus Glacier from Ross Island. It projects 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) into McMurdo Sound from the Ross Island coastline near Cape Evans, Antarctica. The glacier tongue varies in thickness from 50 metres (160 ft) at the snout to 300 metres (980 ft) at the point where it is grounded on the shoreline. Explorers from Robert F. Scott's Discovery Expedition (1901–1904) named and charted the glacier tongue.

Pobeda Ice Island, original Russian name остров Победы, is an ice island in the Mawson Sea. It is located 160 km (99 mi) off the coast of Queen Mary Land, East Antarctica. This island, which exists periodically, is formed by the running aground of a tabular iceberg.

Ice calving, also known as glacier calving or iceberg calving, is the breaking of ice chunks from the edge of a glacier. It is a form of ice ablation or ice disruption. It is the sudden release and breaking away of a mass of ice from a glacier, iceberg, ice front, ice shelf, or crevasse. The ice that breaks away can be classified as an iceberg, but may also be a growler, bergy bit, or a crevasse wall breakaway.

Petermann Glacier is a large glacier located in North-West Greenland to the east of Nares Strait. It connects the Greenland ice sheet to the Arctic Ocean at 81°10' north latitude, near Hans Island.

The Far Eastern Party was a sledging component of the 1911–1914 Australasian Antarctic expedition, which investigated the previously unexplored coastal regions of Antarctica west of Cape Adare. Led by Douglas Mawson, the party aimed to explore the area far to the east of their main base in Adélie Land, pushing about 500 miles (800 km) towards Victoria Land. Accompanying Mawson were Belgrave Edward Ninnis, a lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers, and Swiss ski expert Xavier Mertz; the party used sledge dogs to increase their speed across the ice. Initially they made good progress, crossing two huge glaciers on their route south-east.