The Epistle to the Laodiceans is a purported lost letter of Paul the Apostle, the original existence of which is inferred from an instruction in the Epistle to the Colossians that the congregation should send their letter to the believing community in Laodicea, and likewise obtain a copy of the letter "from Laodicea".

And when this letter has been read among you, have it read also in the church of the Laodiceans; and see that you read also the letter from Laodicea.

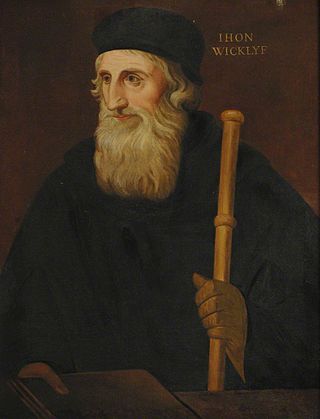

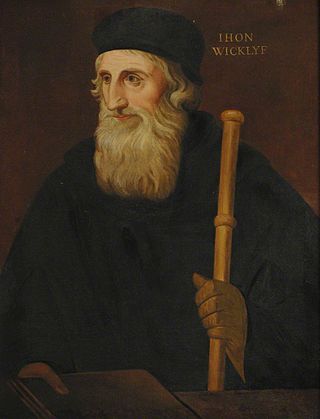

John Wycliffe was an English scholastic philosopher, Christian reformer, priest, and a theology professor at the University of Oxford. Wycliffe is traditionally believed to have advocated or made a vernacular translation of the Vulgate Bible, though more recent scholarship has minimalized the extent of his advocacy or involvement for lack of direct contemporary evidence.

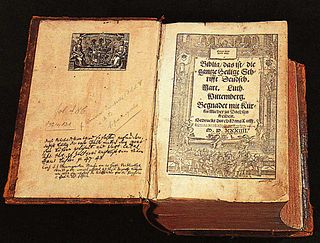

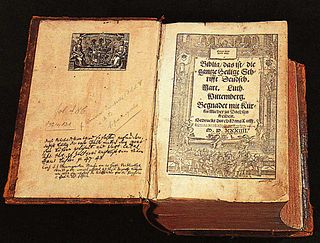

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of King James VI and I. The 80 books of the King James Version include 39 books of the Old Testament, 14 books of Apocrypha, and the 27 books of the New Testament.

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic theologian who was dismissed from the University of Oxford in 1381 for heresy. The Lollards' demands were primarily for reform of Western Christianity. They formulated their beliefs in the Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards.

The Vulgate, sometimes referred to as the Latin Vulgate, is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Bible has been translated into many languages from the biblical languages of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. As of September 2023 all of the Bible has been translated into 736 languages, the New Testament has been translated into an additional 1,658 languages, and smaller portions of the Bible have been translated into 1,264 other languages according to Wycliffe Global Alliance. Thus, at least some portions of the Bible have been translated into 3,658 languages.

Partial Bible translations into languages of the English people can be traced back to the late 7th century, including translations into Old and Middle English. More than 100 complete translations into English have been produced. A number of translations have been prepared of parts of the Bible, some deliberately limited to certain books and some projects that have been abandoned before the planned completion.

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

The Douay–Rheims Bible, also known as the Douay–Rheims Version, Rheims–Douai Bible or Douai Bible, and abbreviated as D–R, DRB, and DRV, is a translation of the Bible from the Latin Vulgate into English made by members of the English College, Douai, in the service of the Catholic Church. The New Testament portion was published in Reims, France, in 1582, in one volume with extensive commentary and notes. The Old Testament portion was published in two volumes twenty-seven years later in 1609 and 1610 by the University of Douai. The first volume, covering Genesis to Job, was published in 1609; the second, covering the Book of Psalms to 2 Maccabees plus the three apocryphal books of the Vulgate appendix following the Old Testament, was published in 1610. Marginal notes took up the bulk of the volumes and offered insights on issues of translation, and on the Hebrew and Greek source texts of the Vulgate.

Wycliffe's Bible or Wycliffite Bibles or Wycliffian Bibles (WYC) are names given for a sequence of Middle English Bible translations believed to have been made under the direction or instigation of English theologian John Wycliffe of the University of Oxford. They are the earliest known literal translations of the entire Bible into English. They appeared over a period from approximately 1382 to 1395.

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards is a Middle English religious text containing statements by leaders of the English medieval movement, the Lollards, inspired by teachings of John Wycliffe. The Conclusions were written in 1395. The text was presented to the Parliament of England and nailed to the doors of Westminster Abbey and St Paul's Cathedral as a placard. The manifesto suggests the expanded treatise Thirty-Seven Conclusions for those that wished more in-depth information.

The Tyndale Bible (TYN) generally refers to the body of biblical translations by William Tyndale into Early Modern English, made c. 1522–1535. Tyndale's biblical text is credited with being the first Anglophone Biblical translation to work directly from Hebrew and Greek texts, although it relied heavily upon the Latin Vulgate and Luther's German New Testament. Furthermore, it was the first English biblical translation that was mass-produced as a result of new advances in the art of printing.

Bible translations in the Middle Ages went through several phases, all using the Vulgate. In the Early Middle Ages, they tended to be associated with royal or episcopal patronage, or with glosses on Latin texts; in the High Middle Ages with monasteries and universities; in the Late Middle Ages, with popular movements which caused, when the movement were associated with violence, official crackdowns of various kinds on vernacular scripture in Spain, England and France.

A Protestant Bible is a Christian Bible whose translation or revision was produced by Protestant Christians. Typically translated into a vernacular language, such Bibles comprise 39 books of the Old Testament and 27 books of the New Testament, for a total of 66 books. Some Protestants use Bibles which also include 14 additional books in a section known as the Apocrypha bringing the total to 80 books. This is in contrast with the 73 books of the Catholic Bible, which includes seven deuterocanonical books as a part of the Old Testament. The division between protocanonical and deuterocanonical books is not accepted by all Protestants who simply view books as being canonical or not and therefore classify books found in the Deuterocanon, along with other books, as part of the Apocrypha. Sometimes the term "Protestant Bible" is simply used as a shorthand for a bible which contains only the 66 books of the Old and New Testaments.

The Bible translations into Latin date back to classical antiquity.

Biblical translations into the indigenous languages of North and South America have been produced since the 16th century.

The Ecclesiae Regimen, also Remonstrance, xxxvii Conclusiones Lollardorum, or Thirty Seven Articles against Corruptions in the Church, is a church reformation declaration against the Catholic Church of England in the Late Middle Ages. It had no official title given to it when written and the author(s) did not identify themselves in the original manuscript. This public declaration by the English medieval sect called the Lollards was announced to the English parliament at the end of the manifesto Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards published in 1395.

Blickling Psalter, also known as Lothian Psalter, is an 8th-century Insular illuminated manuscript containing a Roman Psalter with two additional sets of Old English glosses.

Vetus Latinamanuscripts are handwritten copies of the earliest Latin translations of the Bible, known as the "Vetus Latina" or "Old Latin". They originated prior to Jerome from multiple translators, and differ from Vulgate manuscripts which follow the late-4th-century Latin translation mainly done by Jerome.