Related Research Articles

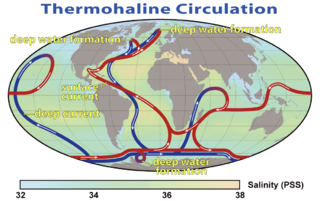

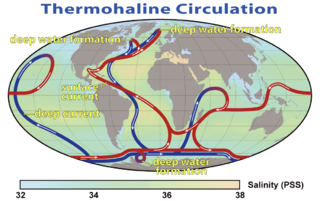

North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) is a deep water mass formed in the North Atlantic Ocean. Thermohaline circulation of the world's oceans involves the flow of warm surface waters from the southern hemisphere into the North Atlantic. Water flowing northward becomes modified through evaporation and mixing with other water masses, leading to increased salinity. When this water reaches the North Atlantic it cools and sinks through convection, due to its decreased temperature and increased salinity resulting in increased density. NADW is the outflow of this thick deep layer, which can be detected by its high salinity, high oxygen content, nutrient minima, high 14C/12C, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

The Drake Passage is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile, Argentina and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean with the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean and extends into the Southern Ocean. The passage is named after the 16th-century English explorer and privateer Sir Francis Drake.

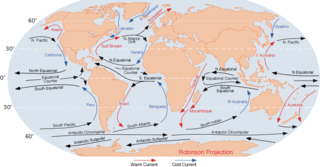

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of seawater generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours, shoreline configurations, and interactions with other currents influence a current's direction and strength. Ocean currents are primarily horizontal water movements.

Physical oceanography is the study of physical conditions and physical processes within the ocean, especially the motions and physical properties of ocean waters.

Thermohaline circulation (THC) is a part of the large-scale ocean circulation that is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and freshwater fluxes. The adjective thermohaline derives from thermo- referring to temperature and -haline referring to salt content, factors which together determine the density of sea water. Wind-driven surface currents travel polewards from the equatorial Atlantic Ocean, cooling en route, and eventually sinking at high latitudes. This dense water then flows into the ocean basins. While the bulk of it upwells in the Southern Ocean, the oldest waters upwell in the North Pacific. Extensive mixing therefore takes place between the ocean basins, reducing differences between them and making the Earth's oceans a global system. The water in these circuits transport both energy and mass around the globe. As such, the state of the circulation has a large impact on the climate of the Earth.

An oceanographic water mass is an identifiable body of water with a common formation history which has physical properties distinct from surrounding water. Properties include temperature, salinity, chemical - isotopic ratios, and other physical quantities which are conservative flow tracers. Water mass is also identified by its non-conservative flow tracers such as silicate, nitrate, oxygen, and phosphate.

The East Greenland Current (EGC) is a cold, low-salinity current that extends from Fram Strait (~80N) to Cape Farewell (~60N). The current is located off the eastern coast of Greenland along the Greenland continental margin. The current cuts through the Nordic Seas and through the Denmark Strait. The current is of major importance because it directly connects the Arctic to the Northern Atlantic, it is a major contributor to sea ice export out of the Arctic, and it is a major freshwater sink for the Arctic.

The Strait of Sicily is the strait between Sicily and Tunisia. The strait is about 145 kilometres (90 mi) wide and divides the Tyrrhenian Sea and the western Mediterranean Sea, from the eastern Mediterranean Sea. The maximum depth is 316 meters (1,037 ft). The island of Pantelleria lies in the middle of the strait.

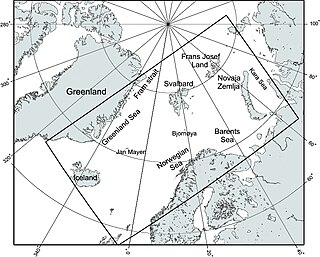

The Greenland Sea is a body of water that borders Greenland to the west, the Svalbard archipelago to the east, Fram Strait and the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Norwegian Sea and Iceland to the south. The Greenland Sea is often defined as part of the Arctic Ocean, sometimes as part of the Atlantic Ocean. However, definitions of the Arctic Ocean and its seas tend to be imprecise or arbitrary. In general usage the term "Arctic Ocean" would exclude the Greenland Sea. In oceanographic studies the Greenland Sea is considered part of the Nordic Seas, along with the Norwegian Sea. The Nordic Seas are the main connection between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans and, as such, could be of great significance in a possible shutdown of thermohaline circulation. In oceanography the Arctic Ocean and Nordic Seas are often referred to collectively as the "Arctic Mediterranean Sea", a marginal sea of the Atlantic.

Lincoln Sea is a body of water in the Arctic Ocean, stretching from Cape Columbia, Canada, in the west to Cape Morris Jesup, Greenland, in the east. The northern limit is defined as the great circle line between those two headlands. It is covered with sea ice throughout the year, the thickest sea ice in the Arctic Ocean, which can be up to 15 m (49 ft) thick. Water depths range from 100 m (330 ft) to 300 m (980 ft). Water and ice from Lincoln Sea empty into Robeson Channel, the northernmost part of Nares Strait, most of the time.

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is part of a global thermohaline circulation in the oceans and is the zonally integrated component of surface and deep currents in the Atlantic Ocean. It is characterized by a northward flow of warm, salty water in the upper layers of the Atlantic, and a southward flow of colder, deep waters. These "limbs" are linked by regions of overturning in the Nordic and Labrador Seas and the Southern Ocean, although the extent of overturning in the Labrador Sea is disputed. The AMOC is an important component of the Earth's climate system, and is a result of both atmospheric and thermohaline drivers.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and introduction to Oceanography.

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately 14,060,000 km2 (5,430,000 sq mi) and is known as one of the coldest of oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, although some oceanographers call it the Arctic Mediterranean Sea. It has also been described as an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. It is also seen as the northernmost part of the all-encompassing World Ocean.

The North Icelandic Jet is a deep-reaching current that flows along the continental slope of Iceland. The North Icelandic Jet advects overflow water into the Denmark Strait and constitutes a pathway that is distinct from the East Greenland Current. It is a cold current that runs west across the top of Iceland, then southwest between Greenland and Iceland at a depth of about 600 metres. The North Icelandic Jet is deep and narrow and can carry more than a million cubic meters of water per second. It was not discovered until 2004.

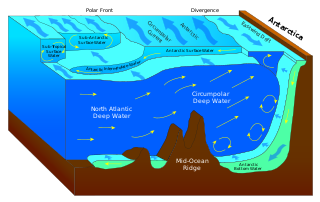

The Denmark Strait overflow is an undersea overflow located in the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland. The overflow transports around 3.2 million m3 (110 million cu ft) of water per second, greatly eclipsing the discharge of the Amazon River into the Atlantic Ocean and the flow rate of the former Guaíra Falls. The descending column of water is approximately 200 m (660 ft) wide and 200 m (660 ft) thick and descends over a length of around 1,000 km (620 mi). It is formed by the density difference of the water masses either side of the Denmark Strait; the southward-flowing water originating from the Nordic Seas is colder and consequently more dense than the Irminger Sea to the south of the strait. At the Greenland–Iceland Rise – an elevated ridge forming the overflow's apex – the colder water cascades along the seafloor to a depth of around 3,000 m (10,000 ft). Due to the Coriolis effect, the downward flow of water is deflected to the right, resulting in the descending water on the Greenland side of the channel being roughly 1 km (0.62 mi) higher than the opposite side of the channel.

The Nordic Seas are located north of Iceland and south of Svalbard. They have also been defined as the region located north of the Greenland-Scotland Ridge and south of the Fram Strait-Spitsbergen-Norway intersection. Known to connect the North Pacific and the North Atlantic waters, this region is also known as having some of the densest waters, creating the densest region found in the North Atlantic Deep Water. The deepest waters of the Arctic Ocean are connected to the worlds other oceans through Nordic Seas and Fram Strait. There are three seas within the Nordic Sea: Greenland Sea, Norwegian Sea, and Iceland Sea. The Nordic Seas only make up about 0.75% of the World's Oceans. This region is known as having diverse features in such a small topographic area, such as the mid oceanic ridge systems. Some locations have shallow shelves, while others have deep slopes and basins. This region, because of the atmosphere-ocean transfer of energy and gases, has varying seasonal climate. During the winter, sea ice is formed in the western and northern regions of the Nordic Seas, whereas during the summer months, the majority of the region remains free of ice.

Cecilie Mauritzen is a Norwegian physical oceanographer who studies connections between ocean currents and climate change.

The Mediterranean Outflow is a current flowing from the Mediterranean Sea towards the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar. Once it has reached the western side of the Strait of Gibraltar, it divides into two branches, one flowing westward following the Iberian continental slope, and another returning to the Strait of Gibraltar circulating cyclonically. In the Strait of Gibraltar and in the Gulf of Cádiz, the Mediterranean Outflow core has a width of a few tens of km. Through its nonlinear interactions with tides and topography, as it flows out of the Mediterranean basin it undergoes such strong mixing that the water masses composing this current become indistinguishable upon reaching the western side of the strait.

Cold and dense water from the Nordic Seas is transported southwards as Faroe-Bank Channel overflow. This water flows from the Arctic Ocean into the North Atlantic through the Faroe-Bank Channel between the Faroe Islands and Scotland. The overflow transport is estimated to contribute to one-third of the total overflow over the Greenland-Scotland Ridge. The remaining two-third of overflow water passes through Denmark Strait, the Wyville Thomson Ridge (0.3 Sv), and the Iceland-Faroe Ridge (1.1 Sv).

The Southern Ocean overturning circulation is a two-cell system in the Southern Ocean that connects different water basins within the global circulation. It is driven by upwelling and downwelling, which are a result of the physical ocean processes that are influenced by freshwater fluxes and wind stress. The global ocean circulation is an essential mechanism in our global climate system due to its influence on the global heat, fresh water and carbon budgets. The upwelling in the upper cell is associated with mid-deep water that is brought to the surface, whereas the upwelling in the lower cell is linked to the fresh and abyssal waters around Antarctica. Around 27 ± 7 Sverdrup (Sv) of deep water wells up to the surface in the Southern Ocean. This upwelled water is partly transformed to lighter water and denser water, respectively 22 ± 4 Sv and 5 ± 5 Sv. The densities of these waters change due to heat and buoyancy fluxes which result in upwelling in the upper cell and downwelling in the lower cell.

References

- ↑ Kida, Shinichiro (2006). Overflows and upper ocean interactions: a mechanism for the Azores current (Ph.D. Thesis). Joint Program in Oceanography/Applied Ocean Science and Engineering, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Department of Ocean Engineering.

- ↑ Käse, R. H.; Girton, J. B.; Sanford, T. B. (June 2003). "Structure and variability of the Denmark Strait Overflow: Model and observations". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 108 (C6). doi:10.1029/2002JC001548. ISSN 0148-0227.