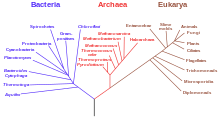

In biology, evolution is the change in heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. Evolution occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, resulting in certain characteristics becoming more or less common within a population over successive generations. The process of evolution has given rise to biodiversity at every level of biological organisation.

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic information of their parents. Through heredity, variations between individuals can accumulate and cause species to evolve by natural selection. The study of heredity in biology is genetics.

Microevolution is the change in allele frequencies that occurs over time within a population. This change is due to four different processes: mutation, selection, gene flow and genetic drift. This change happens over a relatively short amount of time compared to the changes termed macroevolution.

Mendelian inheritance is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularized by William Bateson. These principles were initially controversial. When Mendel's theories were integrated with the Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory of inheritance by Thomas Hunt Morgan in 1915, they became the core of classical genetics. Ronald Fisher combined these ideas with the theory of natural selection in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, putting evolution onto a mathematical footing and forming the basis for population genetics within the modern evolutionary synthesis.

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charles Darwin popularised the term "natural selection", contrasting it with artificial selection, which is intentional, whereas natural selection is not.

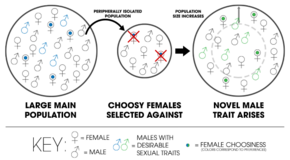

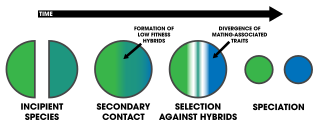

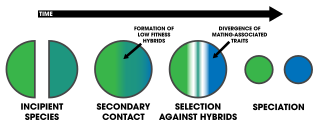

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within lineages. Charles Darwin was the first to describe the role of natural selection in speciation in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species. He also identified sexual selection as a likely mechanism, but found it problematic.

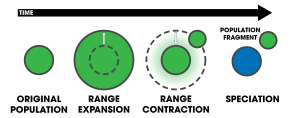

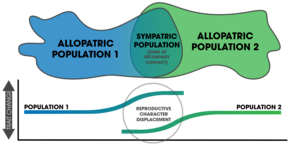

In population genetics, gene flow is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent allele frequencies and therefore can be considered a single effective population. It has been shown that it takes only "one migrant per generation" to prevent populations from diverging due to drift. Populations can diverge due to selection even when they are exchanging alleles, if the selection pressure is strong enough. Gene flow is an important mechanism for transferring genetic diversity among populations. Migrants change the distribution of genetic diversity among populations, by modifying allele frequencies. High rates of gene flow can reduce the genetic differentiation between the two groups, increasing homogeneity. For this reason, gene flow has been thought to constrain speciation and prevent range expansion by combining the gene pools of the groups, thus preventing the development of differences in genetic variation that would have led to differentiation and adaptation. In some cases dispersal resulting in gene flow may also result in the addition of novel genetic variants under positive selection to the gene pool of a species or population

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life forms on Earth. Evolution holds that all species are related and gradually change over generations. In a population, the genetic variations affect the phenotypes of an organism. These changes in the phenotypes will be an advantage to some organisms, which will then be passed onto their offspring. Some examples of evolution in species over many generations are the peppered moth and flightless birds. In the 1930s, the discipline of evolutionary biology emerged through what Julian Huxley called the modern synthesis of understanding, from previously unrelated fields of biological research, such as genetics and ecology, systematics, and paleontology.

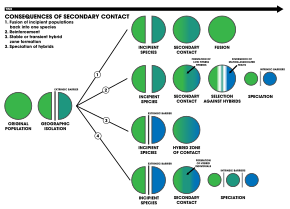

Sympatric speciation is the evolution of a new species from a surviving ancestral species while both continue to inhabit the same geographic region. In evolutionary biology and biogeography, sympatric and sympatry are terms referring to organisms whose ranges overlap so that they occur together at least in some places. If these organisms are closely related, such a distribution may be the result of sympatric speciation. Etymologically, sympatry is derived from the Greek roots συν ("together") and πατρίς ("homeland"). The term was coined by Edward Bagnall Poulton in 1904, who explains the derivation.

This is a list of topics in evolutionary biology.

Disruptive selection, also called diversifying selection, describes changes in population genetics in which extreme values for a trait are favored over intermediate values. In this case, the variance of the trait increases and the population is divided into two distinct groups. In this more individuals acquire peripheral character value at both ends of the distribution curve.

Pleiotropy occurs when one gene influences two or more seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits. Such a gene that exhibits multiple phenotypic expression is called a pleiotropic gene. Mutation in a pleiotropic gene may have an effect on several traits simultaneously, due to the gene coding for a product used by a myriad of cells or different targets that have the same signaling function.

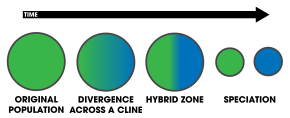

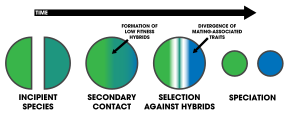

A hybrid zone exists where the ranges of two interbreeding species or diverged intraspecific lineages meet and cross-fertilize. Hybrid zones can form in situ due to the evolution of a new lineage but generally they result from secondary contact of the parental forms after a period of geographic isolation, which allowed their differentiation. Hybrid zones are useful in studying the genetics of speciation as they can provide natural examples of differentiation and (sometimes) gene flow between populations that are at some point between representing a single species and representing multiple species in reproductive isolation.

Genetic divergence is the process in which two or more populations of an ancestral species accumulate independent genetic changes (mutations) through time, often leading to reproductive isolation and continued mutation even after the populations have become reproductively isolated for some period of time, as there isn’t genetic exchange anymore. In some cases, subpopulations cover living in ecologically distinct peripheral environments can exhibit genetic divergence from the remainder of a population, especially where the range of a population is very large. The genetic differences among divergent populations can involve silent mutations or give rise to significant morphological and/or physiological changes. Genetic divergence will always accompany reproductive isolation, either due to novel adaptations via selection and/or due to genetic drift, and is the principal mechanism underlying speciation.

In biology, a cline is a measurable gradient in a single characteristic of a species across its geographical range. First coined by Julian Huxley in 1938, the cline usually has a genetic, or phenotypic character. Clines can show smooth, continuous gradation in a character, or they may show more abrupt changes in the trait from one geographic region to the next.

In biology, evolution is the process of change in all forms of life over generations, and evolutionary biology is the study of how evolution occurs. Biological populations evolve through genetic changes that correspond to changes in the organisms' observable traits. Genetic changes include mutations, which are caused by damage or replication errors in organisms' DNA. As the genetic variation of a population drifts randomly over generations, natural selection gradually leads traits to become more or less common based on the relative reproductive success of organisms with those traits.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to evolution:

Character evolution is the process by which a character or trait evolves along the branches of an evolutionary tree. Character evolution usually refers to single changes within a lineage that make this lineage unique from others. These changes are called character state changes and they are often used in the study of evolution to provide a record of common ancestry. Character state changes can be phenotypic changes, nucleotide substitutions, or amino acid substitutions. These small changes in a species can be identifying features of when exactly a new lineage diverged from an old one.

Reinforcement is a process of speciation where natural selection increases the reproductive isolation between two populations of species. This occurs as a result of selection acting against the production of hybrid individuals of low fitness. The idea was originally developed by Alfred Russel Wallace and is sometimes referred to as the Wallace effect. The modern concept of reinforcement originates from Theodosius Dobzhansky. He envisioned a species separated allopatrically, where during secondary contact the two populations mate, producing hybrids with lower fitness. Natural selection results from the hybrid's inability to produce viable offspring; thus members of one species who do not mate with members of the other have greater reproductive success. This favors the evolution of greater prezygotic isolation. Reinforcement is one of the few cases in which selection can favor an increase in prezygotic isolation, influencing the process of speciation directly. This aspect has been particularly appealing among evolutionary biologists.

Eukaryote hybrid genomes result from interspecific hybridization, where closely related species mate and produce offspring with admixed genomes. The advent of large-scale genomic sequencing has shown that hybridization is common, and that it may represent an important source of novel variation. Although most interspecific hybrids are sterile or less fit than their parents, some may survive and reproduce, enabling the transfer of adaptive variants across the species boundary, and even result in the formation of novel evolutionary lineages. There are two main variants of hybrid species genomes: allopolyploid, which have one full chromosome set from each parent species, and homoploid, which are a mosaic of the parent species genomes with no increase in chromosome number.