Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial disease spread by ticks. It typically begins with a fever and headache, which is followed a few days later with the development of a rash. The rash is generally made up of small spots of bleeding and starts on the wrists and ankles. Other symptoms may include muscle pains and vomiting. Long-term complications following recovery may include hearing loss or loss of part of an arm or leg.

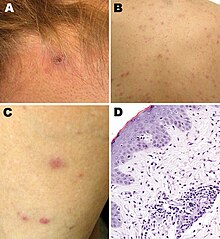

Boutonneuse fever is a fever as a result of a rickettsial infection caused by the bacterium Rickettsia conorii and transmitted by the dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Boutonneuse fever can be seen in many places around the world, although it is endemic in countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. This disease was first described in Tunisia in 1910 by Conor and Bruch and was named boutonneuse due to its papular skin-rash characteristics.

Rickettsia rickettsii is a Gram-negative, intracellular, coccobacillus bacterium that was first discovered in 1902. R. rickettsii is the causative agent of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and is transferred to its host via a tick bite. It is one of the most pathogenic Rickettsia species and affects a large majority of the Western Hemisphere, most commonly the Americas.

An eschar is a slough or piece of dead tissue that is cast off from the surface of the skin, particularly after a burn injury, but also seen in gangrene, ulcer, fungal infections, necrotizing spider bite wounds, tick bites associated with spotted fevers and exposure to cutaneous anthrax. The term ‘eschar’ is not interchangeable with ‘scab’. An eschar contains necrotic tissue whereas a scab is composed of dried blood and exudate.

Tick-borne diseases, which afflict humans and other animals, are caused by infectious agents transmitted by tick bites. They are caused by infection with a variety of pathogens, including rickettsia and other types of bacteria, viruses, and protozoa. The economic impact of tick-borne diseases is considered to be substantial in humans, and tick-borne diseases are estimated to affect ~80 % of cattle worldwide. Most of these pathogens require passage through vertebrate hosts as part of their life cycle. Tick-borne infections in humans, farm animals, and companion animals are primarily associated with wildlife animal reservoirs. many tick-borne infections in humans involve a complex cycle between wildlife animal reservoirs and tick vectors. The survival and transmission of these tick-borne viruses are closely linked to their interactions with tick vectors and host cells. These viruses are classified into different families, including Asfarviridae, Reoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Bunyaviridae, and Flaviviridae.

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families Filoviridae, Flaviviridae, Rhabdoviridae, and several member families of the Bunyavirales order such as Arenaviridae, and Hantaviridae. All types of VHF are characterized by fever and bleeding disorders and all can progress to high fever, shock and death in many cases. Some of the VHF agents cause relatively mild illnesses, such as the Scandinavian nephropathia epidemica, while others, such as Ebola virus, can cause severe, life-threatening disease.

Relapsing fever is a vector-borne disease caused by infection with certain bacteria in the genus Borrelia, which is transmitted through the bites of lice or soft-bodied ticks.

A rickettsiosis is a disease caused by intracellular bacteria.

Orientia tsutsugamushi is a mite-borne bacterium belonging to the family Rickettsiaceae and is responsible for a disease called scrub typhus in humans. It is a natural and an obligate intracellular parasite of mites belonging to the family Trombiculidae. With a genome of only 2.0–2.7 Mb, it has the most repeated DNA sequences among bacterial genomes sequenced so far. The disease, scrub typhus, occurs when infected mite larvae accidentally bite humans. Primarily indicated by undifferentiated febrile illnesses, the infection can be complicated and often fatal.

Rickettsia conorii is a Gram-negative, obligate intracellular bacterium of the genus Rickettsia that causes human disease called boutonneuse fever, Mediterranean spotted fever, Israeli tick typhus, Astrakhan spotted fever, Kenya tick typhus, Indian tick typhus, or other names that designate the locality of occurrence while having distinct clinical features. It is a member of the spotted fever group and the most geographically dispersed species in the group, recognized in most of the regions bordering on the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea, Israel, Kenya, and other parts of North, Central, and South Africa, and India. The prevailing vector is the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. The bacterium was isolated by Emile Brumpt in 1932 and named after A. Conor, who in collaboration with A. Bruch, provided the first description of boutonneuse fever in Tunisia in 1910.

African tick bite fever (ATBF) is a bacterial infection spread by the bite of a tick. Symptoms may include fever, headache, muscle pain, and a rash. At the site of the bite there is typically a red skin sore with a dark center. The onset of symptoms usually occurs 4–10 days after the bite. Complications are rare but may include joint inflammation. Some people do not develop symptoms.

Queensland tick typhus is a zoonotic disease caused by the bacterium Rickettsia australis. It is transmitted by the ticks Ixodes holocyclus and Ixodes tasmani.

Flinders Island spotted fever is a condition characterized by a rash in approximately 85% of cases.

Rickettsia helvetica, previously known as the Swiss agent, is a bacterium found in Dermacentor reticulatus and other ticks, which has been implicated as a suspected but unconfirmed human pathogen. First recognized in 1979 in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Switzerland as a new member of the spotted fever group of Rickettsia, the R. helvetica bacterium was eventually isolated in 1993. Although R. helvetica was initially thought to be harmless in humans and many animal species, some individual case reports suggest that it may be capable of causing a nonspecific fever in humans. In 1997, a man living in eastern France seroconverted to Rickettsia 4 weeks after onset of an unexplained febrile illness. In 2010, a case report indicated that tick-borne R. helvetica can also cause meningitis in humans.

Rickettsia felis is a species of bacterium, the pathogen that causes cat-flea typhus in humans, also known as flea-borne spotted fever. Rickettsia felis also is regarded as the causative organism of many cases of illnesses generally classed as fevers of unknown origin in humans in Africa.

Amblyomma maculatum is a species of tick in the genus Amblyomma. Immatures usually infest small mammals and birds that dwell on the ground; cotton rats may be particularly favored hosts. Some recorded hosts include:

Rickettsia heilongjiangensis is a species of gram negative Alphaproteobacteria, within the spotted fever group, being carried by ticks. It is pathogenic.

The Asian monitor lizard tick, is a hard-bodied tick of the genus Amblyomma. It is found in India, Thailand, Taiwan and Sri Lanka. Adults parasitize various reptiles such as varanids and snakes. These ticks are potential vectors of spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsiae.

Pacific Coast tick fever is an infection caused by Rickettsia philipii. The disease is spread by the Pacific coast ticks. Symptoms may include an eschar. It is within a group known as spotted fever rickettsiosis together with Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and rickettsialpox. These infections can be difficult to tell apart.

Amblyomma triste is a tick in the Amblyomma genus. The tick can be found in Venezuela, Argentina, Brasil, Colombia, Peru and Uruguay. Though not thought to be endemic to North America, a 2010 study found 27 specimens in 18 separate collections that had previously been misidentified in the United States.