A human pathogen is a pathogen that causes disease in humans.

Helicobacter pylori, previously known as Campylobacter pylori, is a gram-negative, flagellated, helical bacterium. Mutants can have a rod or curved rod shape, and these are less effective. Its helical body is thought to have evolved in order to penetrate the mucous lining of the stomach, helped by its flagella, and thereby establish infection. The bacterium was first identified as the causal agent of gastric ulcers in 1983 by the Australian doctors Barry Marshall and Robin Warren.

Melioidosis is an infectious disease caused by a gram-negative bacterium called Burkholderia pseudomallei. Most people exposed to B. pseudomallei experience no symptoms; however, those who do experience symptoms have signs and symptoms that range from mild, such as fever and skin changes, to severe with pneumonia, abscesses, and septic shock that could cause death. Approximately 10% of people with melioidosis develop symptoms that last longer than two months, termed "chronic melioidosis".

Glanders is a contagious zoonotic infectious disease that occurs primarily in horses, mules, and donkeys. It can be contracted by other animals, such as dogs, cats, pigs, goats, and humans. It is caused by infection with the bacterium Burkholderia mallei.

Rickettsia prowazekii is a species of gram-negative, alphaproteobacteria, obligate intracellular parasitic, aerobic bacillus bacteria that is the etiologic agent of epidemic typhus, transmitted in the feces of lice. In North America, the main reservoir for R. prowazekii is the flying squirrel. R. prowazekii is often surrounded by a protein microcapsular layer and slime layer; the natural life cycle of the bacterium generally involves a vertebrate and an invertebrate host, usually an arthropod, typically the human body louse. A form of R. prowazekii that exists in the feces of arthropods remains stably infective for months. R. prowazekii also appears to be the closest semi-free-living relative of mitochondria, based on genome sequencing.

Rickettsia rickettsii is a Gram-negative, intracellular, coccobacillus bacterium that was first discovered in 1902. Having a reduced genome, the bacterium harvests nutrients from its host cell to carry out respiration, making it an organoheterotroph. Maintenance of its genome is carried out through vertical gene transfer where specialization of the bacterium allows it to shuttle host sugars directly into its TCA cycle.

Burkholderia is a genus of Pseudomonadota whose pathogenic members include the Burkholderia cepacia complex, which attacks humans and Burkholderia mallei, responsible for glanders, a disease that occurs mostly in horses and related animals; Burkholderia pseudomallei, causative agent of melioidosis; and Burkholderia cepacia, an important pathogen of pulmonary infections in people with cystic fibrosis (CF). Burkholderia species is also found in marine environments. S.I. Paul et al. (2021) isolated and characterized Burkholderia cepacia from marine sponges of the Saint Martin's Island of the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh.

Corynebacterium diphtheriae is a Gram-positive pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria. It is also known as the Klebs–Löffler bacillus because it was discovered in 1884 by German bacteriologists Edwin Klebs (1834–1912) and Friedrich Löffler (1852–1915). The bacteria are usually harmless unless they are infected by a bacteriophage that carries a gene that gives rise to a toxin. This toxin causes the disease. Diphtheria is caused by the adhesion and infiltration of the bacteria into the mucosal layers of the body, primarily affecting the respiratory tract and the subsequent release of an exotoxin. The toxin has a localized effect on skin lesions, as well as a metastatic, proteolytic effects on other organ systems in severe infections. Originally a major cause of childhood mortality, diphtheria has been almost entirely eradicated due to the vigorous administration of the diphtheria vaccination in the 1910s.

Francisella tularensis is a pathogenic species of Gram-negative coccobacillus, an aerobic bacterium. It is nonspore-forming, nonmotile, and the causative agent of tularemia, the pneumonic form of which is often lethal without treatment. It is a fastidious, facultative intracellular bacterium, which requires cysteine for growth. Due to its low infectious dose, ease of spread by aerosol, and high virulence, F. tularensis is classified as a Tier 1 Select Agent by the U.S. government, along with other potential agents of bioterrorism such as Yersinia pestis, Bacillus anthracis, and Ebola virus. When found in nature, Francisella tularensis can survive for several weeks at low temperatures in animal carcasses, soil, and water. In the laboratory, F. tularensis appears as small rods, and is grown best at 35–37 °C.

Neisseria meningitidis, often referred to as the meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as a coccus because it is round, and more specifically a diplococcus because of its tendency to form pairs.

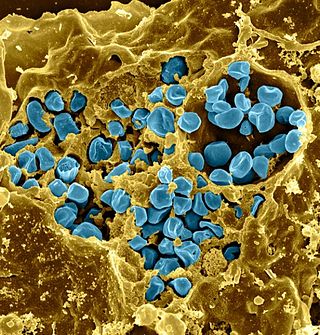

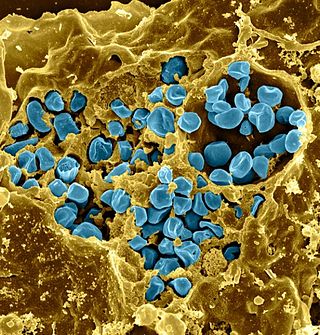

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a Gram-negative, bipolar, aerobic, motile rod-shaped bacterium. It is a soil-dwelling bacterium endemic in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, particularly in Thailand and northern Australia. It was reported in 2008 that there had been an expansion of the affected regions due to significant natural disasters, and it could be found in Southern China, Hong Kong, and countries in America. B. pseudomallei, amongst other pathogens, has been found in monkeys imported into the United States from Asia for laboratory use, posing a risk that the pathogen could be introduced into the country.

Chlamydia felis is a Gram-negative, obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen that infects cats. It is endemic among domestic cats worldwide, primarily causing inflammation of feline conjunctiva, rhinitis and respiratory problems. C. felis can be recovered from the stomach and reproductive tract. Zoonotic infection of humans with C. felis has been reported. Strains FP Pring and FP Cello have an extrachromosomal plasmid, whereas the FP Baker strain does not. FP Cello produces lethal disease in mice, whereas the FP Baker does not. An attenuated FP Baker strain, and an attenuated 905 strain, are used as live vaccines for cats.

Chromobacterium violaceum is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, non-sporing coccobacillus. It is motile with the help of a single flagellum which is located at the pole of the coccobacillus. Usually, there are one or two more lateral flagella as well. It is part of the normal flora of water and soil of tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world. It produces a natural antibiotic called violacein, which may be useful for the treatment of colon and other cancers. It grows readily on nutrient agar, producing distinctive smooth low convex colonies with a characteristic striking dark violet metallic sheen. Some strains of the bacteria which do not produce this pigment have also been reported. It has the ability to break down tarballs.

Burkholderia thailandensis is a nonfermenting motile, Gram-negative bacillus that occurs naturally in soil. It is closely related to Burkholderia pseudomallei, but unlike B. pseudomallei, it only rarely causes disease in humans or animals. The lethal inoculum is approximately 1000 times higher than for B. pseudomallei. It is usually distinguished from B. pseudomallei by its ability to assimilate arabinose. Other differences between these species include lipopolysaccharide composition, colony morphology, and differences in metabolism.

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and are often beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The number of these pathogenic species in humans is estimated to be fewer than a hundred. By contrast, several thousand species are part of the gut flora present in the digestive tract.

Leptospira interrogans is a species of obligate aerobic spirochaete bacteria shaped like a corkscrew with hooked and spiral ends. L. interrogans is mainly found in warmer tropical regions. The bacteria can live for weeks to months in the ground or water. Leptospira is one of the genera of the spirochaete phylum that causes severe mammalian infections. This species is pathogenic to some wild and domestic animals, including pet dogs. It can also spread to humans through abrasions on the skin, where infection can cause flu-like symptoms with kidney and liver damage. Human infections are commonly spread by contact with contaminated water or soil, often through the urine of both wild and domestic animals. Some individuals are more susceptible to serious infection, including farmers and veterinarians who work with animals.

Pathogenomics is a field which uses high-throughput screening technology and bioinformatics to study encoded microbe resistance, as well as virulence factors (VFs), which enable a microorganism to infect a host and possibly cause disease. This includes studying genomes of pathogens which cannot be cultured outside of a host. In the past, researchers and medical professionals found it difficult to study and understand pathogenic traits of infectious organisms. With newer technology, pathogen genomes can be identified and sequenced in a much shorter time and at a lower cost, thus improving the ability to diagnose, treat, and even predict and prevent pathogenic infections and disease. It has also allowed researchers to better understand genome evolution events - gene loss, gain, duplication, rearrangement - and how those events impact pathogen resistance and ability to cause disease. This influx of information has created a need for bioinformatics tools and databases to analyze and make the vast amounts of data accessible to researchers, and it has raised ethical questions about the wisdom of reconstructing previously extinct and deadly pathogens in order to better understand virulence.

Pathema was one of the eight bioinformatics resource centers funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a component of the National Institute of Health (NIH), which is an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Escherichia coli is a gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms). Most E. coli strains are harmless, but pathogenic varieties cause serious food poisoning, septic shock, meningitis, or urinary tract infections in humans. Unlike normal flora E. coli, the pathogenic varieties produce toxins and other virulence factors that enable them to reside in parts of the body normally not inhabited by E. coli, and to damage host cells. These pathogenic traits are encoded by virulence genes carried only by the pathogens.

In biology, a pathogen, in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ.