Living things, especially animals [1] and plants, [2] play many roles in culture, where culture means all forms of practice and expression transmitted by social learning. [3]

Culture is the social behavior and norms found in human societies. Culture is considered a central concept in anthropology, encompassing the range of phenomena that are transmitted through social learning in human societies. Cultural universals are found in all human societies; these include expressive forms like art, music, dance, ritual, religion, and technologies like tool usage, cooking, shelter, and clothing. The concept of material culture covers the physical expressions of culture, such as technology, architecture and art, whereas the immaterial aspects of culture such as principles of social organization, mythology, philosophy, literature, and science comprise the intangible cultural heritage of a society.

Contents

- Context

- Practical uses

- For food and materials

- For work and transport

- In science

- For medicines and drugs

- For pleasure

- Symbolic uses

- In art

- In literature and film

- In mythology and religion

- References

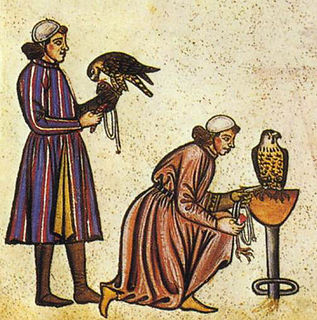

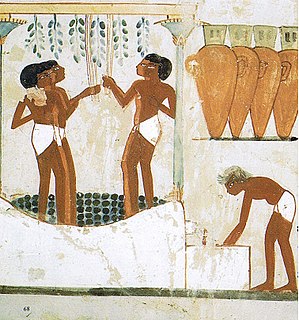

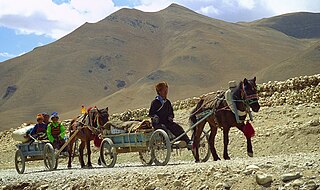

Plants provide the greater part of the food for people and their domestic animals: much of human culture and civilisation came into being through agriculture. While a large number of plants have been used for food, a small number of staple crops including wheat, rice, and maize provide most of the food in the world today. In turn, animals provide much of the meat eaten by the human population, whether farmed or hunted, and until the arrival of mechanised transport, terrestrial mammals provided a large part of the power used for work and transport. A variety of living things serve as models in biological research, such as in genetics, and in drug testing. Until the 19th century, plants yielded most of the medicinal drugs in common use, as described in the 1st century by Dioscorides. Plants are the source of many psychoactive drugs, some such as coca known to have been used for thousands of years. Yeast, a fungus, has been used to ferment cereals such as wheat and barley to make bread and beer; other fungi such as Psilocybe and fly agaric mushrooms have been gathered as psychoactive drugs.

Food is any substance consumed to provide nutritional support for an organism. It is usually of plant or animal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ingested by an organism and assimilated by the organism's cells to provide energy, maintain life, or stimulate growth.

Agriculture is the science and art of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to live in cities. The history of agriculture began thousands of years ago. After gathering wild grains beginning at least 105,000 years ago, nascent farmers began to plant them around 11,500 years ago. Pigs, sheep and cattle were domesticated over 10,000 years ago. Plants were independently cultivated in at least 11 regions of the world. Industrial agriculture based on large-scale monoculture in the twentieth century came to dominate agricultural output, though about 2 billion people still depended on subsistence agriculture into the twenty-first.

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain which is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus Triticum; the most widely grown is common wheat.

Many species of animal are kept as pets, the most popular being mammals, especially dogs and cats. Plants are grown for pleasure in gardens and greenhouses, yielding flowers, shade, and decorative foliage; some, such as cactuses, able to tolerate dry conditions, are grown as houseplants.

A pet or companion animal is an animal kept primarily for a person's company, protection, entertainment, or as an act of compassion such as taking in and protecting a hungry stray cat, rather than as a working animal, livestock, or laboratory animal. Popular pets are often noted for their attractive appearances, intelligence, and relatable personalities, or may just be accepted as they are because they need a home.

The domestic dog is a member of the genus Canis (canines), which forms part of the wolf-like canids, and is the most widely abundant terrestrial carnivore. The dog and the extant gray wolf are sister taxa as modern wolves are not closely related to the wolves that were first domesticated, which implies that the direct ancestor of the dog is extinct. The dog was the first species to be domesticated and has been selectively bred over millennia for various behaviors, sensory capabilities, and physical attributes.

The cat is a small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and often referred to as the domestic cat to distinguish it from wild members of the family. The cat is either a house cat, kept as a pet, or a feral cat, freely ranging and avoiding human contact. A house cat is valued by humans for companionship and for its ability to hunt rodents. About 60 cat breeds are recognized by various cat registries.

Animals such as horses and deer are among the earliest subjects of art, being found in the Upper Paleolithic cave paintings such as at Lascaux.

The horse is one of two extant subspecies of Equus ferus. It is an odd-toed ungulate mammal belonging to the taxonomic family Equidae. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million years from a small multi-toed creature, Eohippus, into the large, single-toed animal of today. Humans began domesticating horses around 4000 BC, and their domestication is believed to have been widespread by 3000 BC. Horses in the subspecies caballus are domesticated, although some domesticated populations live in the wild as feral horses. These feral populations are not true wild horses, as this term is used to describe horses that have never been domesticated, such as the endangered Przewalski's horse, a separate subspecies, and the only remaining true wild horse. There is an extensive, specialized vocabulary used to describe equine-related concepts, covering everything from anatomy to life stages, size, colors, markings, breeds, locomotion, and behavior.

Deer are the hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the fallow deer, and the chital; and the Capreolinae, including the reindeer (caribou), the roe deer, and the moose. Female reindeer, and male deer of all species except the Chinese water deer, grow and shed new antlers each year. In this they differ from permanently horned antelope, which are part of a different family (Bovidae) within the same order of even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla).

Art is a diverse range of human activities in creating visual, auditory or performing artifacts (artworks), expressing the author's imaginative, conceptual ideas, or technical skill, intended to be appreciated for their beauty or emotional power. In their most general form these activities include the production of works of art, the criticism of art, the study of the history of art, and the aesthetic dissemination of art.

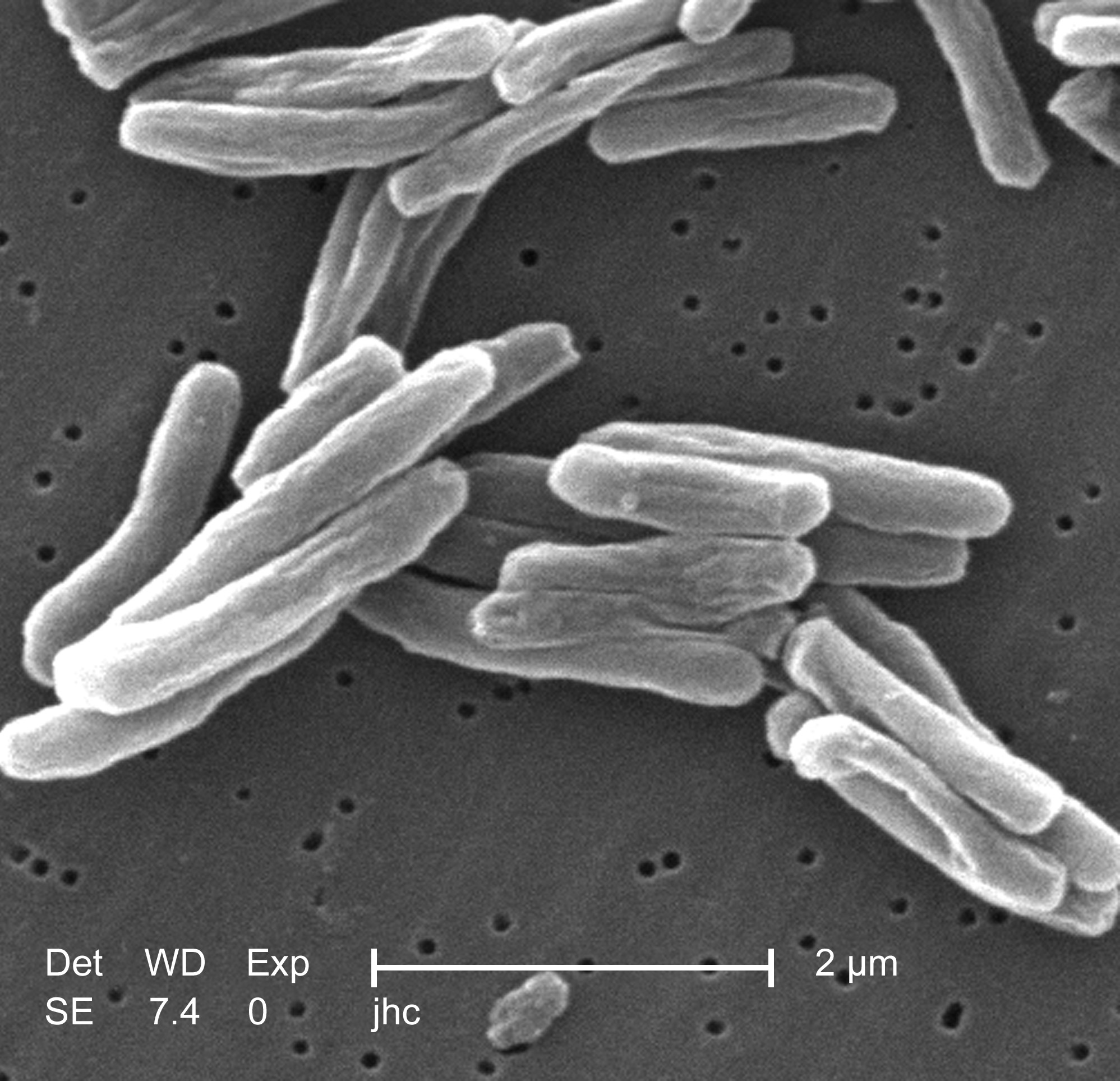

Living things further play a wide variety of symbolic roles in literature, film, mythology, and religion. Sometimes a major disease like tuberculosis, caused by a bacterium, plays a role in culture, in its case being associated for some reason with artistic creativity.

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of part or all of an organism, and that is not due to any external injury. Diseases are often construed as medical conditions that are associated with specific symptoms and signs. A disease may be caused by external factors such as pathogens or by internal dysfunctions. For example, internal dysfunctions of the immune system can produce a variety of different diseases, including various forms of immunodeficiency, hypersensitivity, allergies and autoimmune disorders.

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections do not have symptoms, in which case it is known as latent tuberculosis. About 10% of latent infections progress to active disease which, if left untreated, kills about half of those affected. The classic symptoms of active TB are a chronic cough with blood-containing sputum, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. It was historically called "consumption" due to the weight loss. Infection of other organs can cause a wide range of symptoms.

Through its effect on the world's population and major artists in various fields, tuberculosis has influenced history. The disease was for centuries associated with poetic and artistic qualities in its sufferers, and was known as "the romantic disease". Many artistic figures including the poet John Keats, the composer Frédéric Chopin and the artist Edvard Munch either had the disease or were close to others who did.