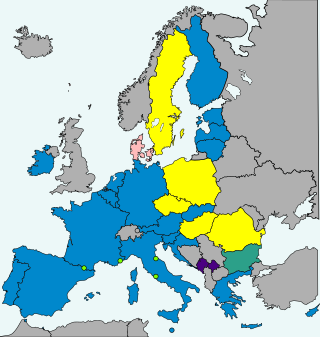

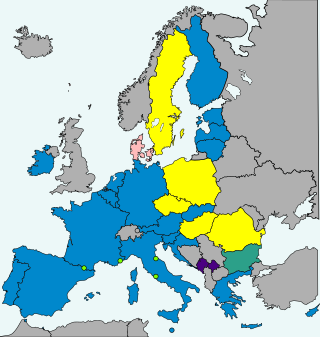

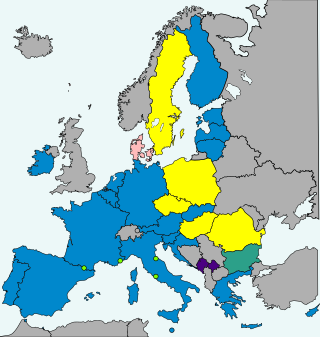

The euro area, commonly called the eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 20 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU policies.

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) is an agreement, among all the 27 member states of the European Union, to facilitate and maintain the stability of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Based primarily on Articles 121 and 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, it consists of fiscal monitoring of members by the European Commission and the Council of the European Union, and the issuing of a yearly recommendation for policy actions to ensure a full compliance with the SGP also in the medium-term. If a Member State breaches the SGP's outlined maximum limit for government deficit and debt, the surveillance and request for corrective action will intensify through the declaration of an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP); and if these corrective actions continue to remain absent after multiple warnings, the Member State can ultimately be issued economic sanctions. The pact was outlined by a resolution and two council regulations in July 1997. The first regulation "on the strengthening of the surveillance of budgetary positions and the surveillance and coordination of economic policies", known as the "preventive arm", entered into force 1 July 1998. The second regulation "on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit procedure", known as the "dissuasive arm", entered into force 1 January 1999.

The euro convergence criteria are the criteria European Union member states are required to meet to enter the third stage of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and adopt the euro as their currency. The four main criteria, which actually comprise five criteria as the "fiscal criterion" consists of both a "debt criterion" and a "deficit criterion", are based on Article 140 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Latvia replaced its previous currency, the lats, with the euro on 1 January 2014, after a European Union (EU) assessment in June 2013 asserted that the country had met all convergence criteria necessary for euro adoption. The adoption process began 1 May 2004, when Latvia joined the European Union, entering the EU's Economic and Monetary Union. At the start of 2005, the lats was pegged to the euro at Ls 0.702804 = €1, and Latvia joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, four months later on 2 May 2005.

Romania's national currency is the leu. After Romania joined the European Union (EU) in 2007, the country became required to replace the leu with the euro once it meets all four euro convergence criteria, as stated in article 140 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. As of 2023, the only currency on the market is the leu and the euro is not yet used in shops. The Romanian leu is not part of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, although Romanian authorities are working to prepare the changeover to the euro. To achieve the currency changeover, Romania must undergo at least two years of stability within the limits of the convergence criteria. The current Romanian government established a self-imposed criterion to reach a certain level of real convergence as a steering anchor to decide the appropriate target year for ERM II membership and Euro adoption. In March 2018, the National Plan for the Adoption of the Euro scheduled the date for euro adoption in Romania as 2024. Nevertheless, in early 2021, this date was postponed to 2027 or 2028, and once again to 2029 in late 2021 and then moved up to 2026.

The euro came into existence on 1 January 1999, although it had been a goal of the European Union (EU) and its predecessors since the 1960s. After tough negotiations, the Maastricht Treaty entered into force in 1993 with the goal of creating an economic and monetary union (EMU) by 1999 for all EU states except the UK and Denmark.

Eurobonds or stability bonds were proposed government bonds to be issued in euros jointly by the European Union's 19 eurozone states. The idea was first raised by the Barroso European Commission in 2011 during the 2009–2012 European sovereign debt crisis. Eurobonds would be debt investments whereby an investor loans a certain amount of money, for a certain amount of time, with a certain interest rate, to the eurozone bloc altogether, which then forwards the money to individual governments. The proposal was floated again in 2020 as a potential response to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe, leading such debt issue to be dubbed "corona bonds".

The Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) is one of the oldest configurations of the Council of the European Union and is composed of the economics and finance ministers of the 27 European Union member states, as well as Budget Ministers when budgetary issues are discussed.

The European debt crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis or the European sovereign debt crisis, was a multi-year debt crisis that took place in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until the mid to late 2010s. Several eurozone member states were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or to bail out over-indebted banks under their national supervision without the assistance of third parties like other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The economic and monetary union (EMU) of the European Union is a group of policies aimed at converging the economies of member states of the European Union at three stages.

Fiscal union is the integration of the fiscal policy of nations or states. In a fiscal union, decisions about the collection and expenditure of taxes are taken by common institutions, shared by the participating governments. A fiscal union does not imply the centralisation of spending and tax decisions at the supranational level. Centralisation of these decisions would open up not only the possibility of inherent risk sharing through the supranational tax and transfer system but also economic stabilisation through debt management at the supranational level. Proper management would reduce the effects of asymmetric shocks that would be shared both with other countries and with future generations. Fiscal union also implies that the debt would be financed not by individual countries but by a common bond.

The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is an intergovernmental organization located in Luxembourg City, which operates under public international law for all eurozone member states having ratified a special ESM intergovernmental treaty. It was established on 27 September 2012 as a permanent firewall for the eurozone, to safeguard and provide instant access to financial assistance programmes for member states of the eurozone in financial difficulty, with a maximum lending capacity of €500 billion. It has replaced two earlier temporary EU funding programmes: the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM).

The Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union; also referred to as TSCG, or more plainly the Fiscal Stability Treaty is an intergovernmental treaty introduced as a new stricter version of the Stability and Growth Pact, signed on 2 March 2012 by all member states of the European Union (EU), except the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom. The treaty entered into force on 1 January 2013 for the 16 states which completed ratification prior to this date. As of 3 April 2019, it had been ratified and entered into force for all 25 signatories plus Croatia, which acceded to the EU in July 2013, and the Czech Republic.

Audits of Greece's public finances during the period 2009–2010 were undertaken by the EU authorities. Since joining the Euro zone, Greece's public finances markedly deviated from the debt and deficit limits set by Stability and Growth Pact.

The 2010–2014 Portuguese financial crisis was part of the wider downturn of the Portuguese economy that started in 2001 and possibly ended between 2016 and 2017. The period from 2010 to 2014 was probably the hardest and more challenging part of the entire economic crisis; this period includes the 2011–14 international bailout to Portugal and was marked by intense austerity policies, more intense than the wider 2001-2017 crisis. Economic growth stalled in Portugal between 2001 and 2002, and following years of internal economic crisis, the worldwide Great Recession started to hit Portugal in 2008 and eventually led to the country being unable to repay or refinance its government debt without the assistance of third parties. To prevent an insolvency situation in the debt crisis, Portugal applied in April 2011 for bail-out programs and drew a cumulated €78 billion from the IMF, the EFSM, and the EFSF. Portugal exited the bailout in May 2014, the same year that positive economic growth re-appeared following three years of recession. The government achieved a 2.1% budget deficit in 2016 and in 2017 the economy grew 2.7%.

The Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP) is a set of European Union regulations designed to prevent and correct risky macroeconomic developments within EU member states, such as high current account deficits, unsustainable external indebtedness and housing bubbles. It was introduced by the EU in autumn 2011 amidst the economic and financial crisis, and entered into force on 13 December 2011. The MIP is part of the EU's "Sixpack" legislation, which aims to reinforce the monitoring and surveillance of macroeconomic policies in the EU and the euro area.

The Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) is one of the pillars of the European Union's banking union. The Single Resolution Mechanism entered into force on 19 August 2014 and is directly responsible for the resolution of the entities and groups directly supervised by the European Central Bank as well as other cross-border groups. The centralised decision making is built around the Single Resolution Board (SRB) consisting of a chair, a Vice Chair, four permanent members, and the relevant national resolution authorities.

CMFB, in the context of European statistics, stands for Committee on Monetary, Financial and Balance of Payments Statistics. Originally established in 1991, the Committee is an advisory committee for the European Commission (Eurostat) and European Central Bank and a platform for cooperation between the statistical and central banking community in Europe.

The European Semester of the European Union was established in 2010 as an annual cycle of economic and fiscal policy coordination. It provides a central framework of processes within the EU socio-economic governance. The European Semester is a core component of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and it annually aggregates different processes of control, surveillance and coordination of budgetary, fiscal, economic and social policies. It also offers a large space for discussions and interactions between the European institutions and Member States. As a recurrent cycle of budgetary cooperation among the EU Member States, it runs from November to June and is preceded in each country by a national semester running from July to October in which the recommendations introduced by the Commission and approved by the Council are to be adopted by national parliaments and construed into national legislation. The European Semester has evolved over the years with a gradual inclusion of social, economic, and employment objectives and it is governed by mainly three pillars which are a combination of hard and soft law due a mix of surveillance mechanisms and possible sanctions with coordination processes. The main objectives of the European Semester are noted as: contributing to ensuring convergence and stability in the EU; contributing to ensuring sound public finances; fostering economic growth; preventing excessive macroeconomic imbalances in the EU; and implementing the Europe 2020 strategy. However, the rate of the implementation of the recommendations adopted during the European Semester has been disappointing and has gradually declined since its initiation in 2011 which has led to an increase in the debate/criticism towards the effectiveness of the European Semester.