This timeline of mosasaur research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, and taxonomic revisions of mosasaurs, a group of giant marine lizards that lived during the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Although mosasaurs went extinct millions of years before humans evolved, humans have coexisted with mosasaur fossils for millennia. Before the development of paleontology as a formal science, these remains would have been interpreted through a mythological lens. Myths about warfare between serpentine water monsters and aerial thunderbirds told by the Native Americans of the modern western United States may have been influenced by observations of mosasaur fossils and their co-occurrence with creatures like Pteranodon and Hesperornis . [1]

Contents

- Prescientific

- 18th century

- 1760s

- 1770s

- 1780s

- 1790s

- 19th century

- 1800s

- 1810s

- 1820s

- 1830s

- 1840s

- 1850s

- 1860s

- 1870s

- 1880s

- 1890s

- 20th century

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1920s

- 1930s

- 1940s

- 1950s

- 1960s

- 1970s

- 1980s

- 1990s

- 21st century

- 2000s

- 2010s

- 2020s

- See also

- Footnotes

- References

- External links

The scientific study of mosasaurs began in the late 18th century with the serendipitous discovery of a large fossilized skeleton in a limestone mine near Maastricht in the Netherlands. [2] The fossils were studied by local scholar Adriaan Gilles Camper, who noted a resemblance to modern monitor lizards in correspondence with renowned French anatomist Georges Cuvier. [3] Nevertheless, the animal was not scientifically described until the English Reverend William Daniel Conybeare named it Mosasaurus , after the river Meuse located near the site of its discovery. [4]

By this time the first mosasaur fossils from the United States were discovered by the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and the first remains in the country to be scientifically described were reported slightly later from New Jersey. [5] This was followed by an avalanche of discoveries by the feuding Bone War paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Kansas. [6] By the end of the century a specimen of Tylosaurus would be found that preserved its scaley skin. [7] Later Samuel Wendell Williston mistook fossilized tracheal rings for the remains of a fringe of skin running down the animal's back, which subsequently became a common inaccuracy in artistic restorations. [8]

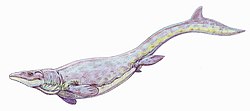

The 20th century soon saw the discovery in Alabama of a strange mosasaur called Globidens , with rounded teeth suited to crushing shells. [9] Mosasaur remains were also discovered in Africa and California. [10] In 1967 Dale Russell published a scientific monograph dedicated to mosasaurs. [11] Embryonic remains in the 1990s confirmed that mosasaurs gave live birth like in ichthyosaurs. [12] The 1990s also saw a revival and escalation of a debate regarding whether or not some supposed mosasaur toothmarks in ammonoid shells were actually made by limpets. [13] By the end of the century, the evolutionary relationship between mosasaurs and snakes as well as the possible involvement of mosasaurs in the extinction of the aforementioned ichthyosaurs became hot button controversies. [14]

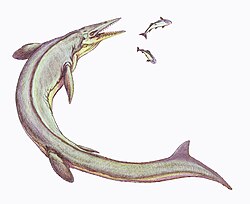

The debates regarding snakes, toothmarks, and ichthyosaurs spilled over into the early 21st century. These discussions were also accompanied by the discovery of many new taxa, including new species of Globidens, Mosasaurus, and Tylosaurus as well as entirely new genera like Yaguarasaurus and Tethysaurus . [15] In 2013, Lindgren, Kaddumi, and Polcyn reported the discovery of a Prognathodon specimen from Jordan that preserved the soft tissues of its scaley skin, flippers and tail. Significantly, the tail resembled those of modern carcharinid sharks, although the bottom lobe of the tail fin was longest in the mosasaur whereas shark tails have longer upper lobes. [16]