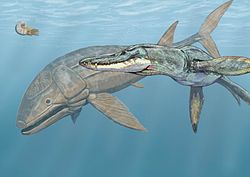

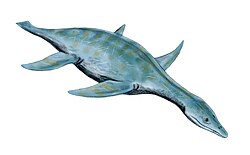

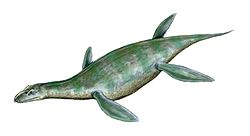

This timeline of plesiosaur research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, taxonomic revisions, and cultural portrayals of plesiosaurs, an order of marine reptiles that flourished during the Mesozoic Era. The first scientifically documented plesiosaur fossils were discovered during the early 19th century by Mary Anning. [1] Plesiosaurs were actually discovered and described before dinosaurs. [2] They were also among the first animals to be featured in artistic reconstructions of the ancient world, and therefore among the earliest prehistoric creatures to attract the attention of the lay public. [3] Plesiosaurs were originally thought to be a kind of primitive transitional form between marine life and terrestrial reptiles. However, now plesiosaurs are recognized as highly derived marine reptiles descended from terrestrial ancestors. [4]

Contents

- Prescientific

- 18th century

- 1719

- 19th century

- 1810s

- 1820s

- 1830s

- 1840s

- 1860s

- 1870s

- 1880s

- 1890s

- 20th century

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1920s

- 1930s

- 1940s

- 1950s

- 1960s

- 1970s

- 1980s

- 1990s

- 21st century

- 2000s

- 2010s

- 2020s

- See also

- Footnotes

- References

- A-F

- G-L

- M-R

- S-Z

- External links

Early researchers thought that plesiosaurs laid eggs like most reptiles. They commonly imagined plesiosaurs crawling up beaches and burying eggs like turtles. However, later opinion shifted towards the idea that plesiosaurs gave live birth and never went on dry land: the biggest genera may have been too heavy to go on land at all, but smaller genera could've been capable. [5] Plesiosaur locomotion has been a source of continuous controversy among paleontologists. [6] The earliest speculations on the subject during the 19th century saw plesiosaur swimming as analogous to the paddling of modern sea turtles. During the 1920s opinion shifted to the idea that plesiosaurs swam with a rowing motion. [7] However, a paper published in 1975 that once more found support for sea turtle-like swimming in plesiosaurs. [8] This conclusion reignited the controversy regarding plesiosaur locomotion through the late 20th century. [9] In 2011, F. Robin O'Keefe and Luis M. Chiappe concluded the debate on plesiosaur reproduction, reporting the discovery of a gravid female plesiosaur with a single large embryo preserved inside her. [10]