The human microbiome is the aggregate of all microbiota that reside on or within human tissues and biofluids along with the corresponding anatomical sites in which they reside, including the skin, mammary glands, seminal fluid, uterus, ovarian follicles, lung, saliva, oral mucosa, conjunctiva, biliary tract, and gastrointestinal tract. Types of human microbiota include bacteria, archaea, fungi, protists and viruses. Though micro-animals can also live on the human body, they are typically excluded from this definition. In the context of genomics, the term human microbiome is sometimes used to refer to the collective genomes of resident microorganisms; however, the term human metagenome has the same meaning.

Mollicutes is a class of bacteria distinguished by the absence of a cell wall. The word "Mollicutes" is derived from the Latin mollis, and cutis. Individuals are very small, typically only 0.2–0.3 μm in size and have a very small genome size. They vary in form, although most have sterols that make the cell membrane somewhat more rigid. Many are able to move about through gliding, but members of the genus Spiroplasma are helical and move by twisting. The best-known genus in the Mollicutes is Mycoplasma.

The Clostridia are a highly polyphyletic class of Firmicutes, including Clostridium and other similar genera. They are distinguished from the Bacilli by lacking aerobic respiration. They are obligate anaerobes and oxygen is toxic to them. Species of the class Clostridia are often but not always Gram-positive and have the ability to form spores. Studies show they are not a monophyletic group, and their relationships are not entirely certain. Currently, most are placed in a single order called Clostridiales, but this is not a natural group and is likely to be redefined in the future.

Gutmicrobiota are the microorganisms including bacteria, archaea and microscopic eukaryotes that live in the digestive tracts of humans and other animals including insects. Alternative terms include gutflora and microbiome. The gastrointestinal metagenome is the aggregate of all the genomes of gut microbiota. The gut is the main location of human microbiota. The gut microbiota has broad impacts, including effects on colonization resistance to pathogens, maintaining the intestinal epithelium, metabolizing dietary and pharmaceutical compounds, controlling immune function, and even behavior thorugh the gut-brain axis.

Fibrobacteres is a small bacterial phylum which includes many of the major rumen bacteria, allowing for the degradation of plant-based cellulose in ruminant animals. Members of this phylum were categorized in other phyla. The genus Fibrobacter was removed from the genus Bacteroides in 1988.

Bacteroides is a genus of Gram-negative, obligate anaerobic bacteria. Bacteroides species are non endospore-forming bacilli, and may be either motile or nonmotile, depending on the species. The DNA base composition is 40–48% GC. Unusual in bacterial organisms, Bacteroides membranes contain sphingolipids. They also contain meso-diaminopimelic acid in their peptidoglycan layer.

Dysbiosis is characterized as a disruption to the microbiota homeostasis caused by an imbalance in the microflora, changes in their functional composition and metabolic activities, or a shift in their local distribution. It is a term for a microbial imbalance or maladaptation on or inside the body, such as an impaired microbiota. For example, a part of the human microbiota, such as the skin flora, gut flora, or vaginal flora, can become deranged, with normally dominating species underrepresented and normally outcompeted or contained species increasing to fill the void. Dysbiosis is most commonly reported as a condition in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly during small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or small intestinal fungal overgrowth (SIFO).

The term "infectobesity" refers to the hypothesis that obesity could have an infectious origin and the emerging field of medical research that studies the relationship between pathogens and weight gain. The term was coined in 2001 by Dr. Nikhil V. Dhurandhar, at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center.

Jeffrey I. Gordon is a biologist and the Dr. Robert J. Glaser Distinguished University Professor and Director of the Center for Genome Sciences and Systems Biology at Washington University in St. Louis. He is internationally known for his research on gastrointestinal development and how gut microbial communities affect normal intestinal function, shape various aspects of human physiology including our nutritional status, and affect predisposition to diseases. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, and the American Philosophical Society.

Microbiota are "ecological communities of commensal, symbiotic and pathogenic microorganisms" found in and on all multicellular organisms studied to date from plants to animals. Microbiota include bacteria, archaea, protists, fungi and viruses. Microbiota have been found to be crucial for immunologic, hormonal and metabolic homeostasis of their host. The term microbiome describes either the collective genomes of the microorganisms that reside in an environmental niche or the microorganisms themselves.

Prevotella is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria.

Akkermansia is a genus in the phylum Verrucomicrobia (Bacteria). The genus was first proposed in 2004 by Muriel Derrien and others, with the type species Akkermansia muciniphila.

The Erysipelotrichia are a class of bacteria of the phylum Firmicutes. Species of this class are known to be common in the gut microbiome, as they have been isolated from swine manure and increase in composition of the mouse gut microbiome for mice switched to diets high in fat.

Parasutterella is a genus of Gram-negative, circular/rod-shaped, obligate anaerobic, non-spore forming bacteria from the Proteobacteria phylum, Betaproteobacteria class and the family Sutterellaceae. Previously, this genus was considered "unculturable," meaning that it could not be characterized through conventional laboratory techniques, such as grow in culture due its unique requirements of anaerobic environment. The genus was initially discovered through 16S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. By analyzing the sequence similarity, Parasutterella was determined to be related most closely to the genus Sutterella and previously classified in the family Alcaligenaceae.

Skin immunity is a property of skin that allows it to resist infections from pathogens. In addition to providing a passive physical barrier against infection, the skin also contains elements of the innate and adaptive immune systems which allows it to actively fight infections. Hence the skin provides defense in depth against infection.

Akkermansia muciniphila is a species of human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium, the type species for a new genus, Akkermansia, proposed in 2004 by Muriel Derrien and Willem de Vos. Extensive research is being undertaken to understand its association with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and inflammation.

Microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs) are carbohydrates that are resistant to digestion by a host's metabolism, and are made available for gut microbes, as prebiotics, to ferment or metabolize into beneficial compounds, such as short chain fatty acids. The term, ‘‘microbiota-accessible carbohydrate’’ contributes to a conceptual framework for investigating and discussing the amount of metabolic activity that a specific food or carbohydrate can contribute to a host's microbiota.

The microbiota describes the sum of all symbiotic microorganisms living on or in an organism. The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is a model organism and known as one of the most investigated organisms worldwide. The microbiota in flies is less complex than that found in humans. It still has an influence on the fitness of the fly, and it affects different life-history characteristics such as lifespan, resistance against pathogens (immunity) and metabolic processes (digestion). Considering the comprehensive toolkit available for research in Drosophila, analysis of its microbiome could enhance our understanding of similar processes in other types of host-microbiota interactions, including those involving humans. Microbiota plays key roles in the intestinal immune and metabolic responses via their fermentation product, acetate.

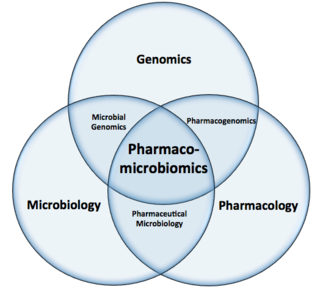

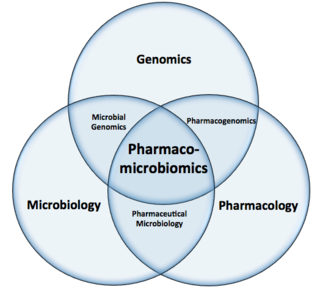

Pharmacomicrobiomics, first used in 2010, is defined as the effect of microbiome variations on drug disposition, action, and toxicity. Pharmacomicrobiomics is concerned with the interaction between xenobiotics, or foreign compounds, and the gut microbiome. It is estimated that over 100 trillion prokaryotes representing more than 1000 species reside in the gut. Within the gut, microbes help modulate developmental, immunological and nutrition host functions. The aggregate genome of microbes extends the metabolic capabilities of humans, allowing them to capture nutrients from diverse sources. Namely, through the secretion of enzymes that assist in the metabolism of chemicals foreign to the body, modification of liver and intestinal enzymes, and modulation of the expression of human metabolic genes, microbes can significantly impact the ingestion of xenobiotics.

Modulibacteria is a bacterial phylum formerly known as KS3B3 or GN06. It is a candidate phylum, meaning there are no cultured representatives of this group. Members of the Modulibacteria phylum are known to cause fatal filament overgrowth (bulking) in high-rate industrial anaerobic wastewater treatment bioreactors.