History

Ancient

In Greek mythology, various contacts with the part of the world that was later named Russia or the Soviet Union are recorded. The area was vaguely described as the Hyperborea ("beyond the North wind") and its mythical inhabitants, the Hyperboreans, were said to have lived blissfully under eternal sunshine. Medea was a princess of Colchis, modern western Georgia, and was entangled in the myth of Jason and the Golden Fleece. The Amazons, a race of fierce female warriors, were placed by Herodotus in Sarmatia (modern Southern Russia and Southern Ukraine). [1]

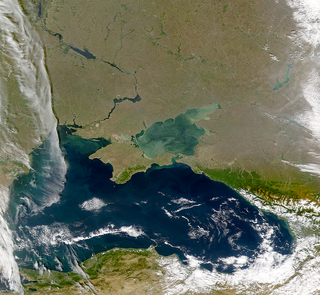

In historical times, Greeks have lived in the present Black Sea region of Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States since long before the foundation of Kievan Rus', the first Russian state. The Greek name of Crimea was Tauris, and in mythology it was the home of the tribes who took Iphigenia prisoner in Euripides' play Iphigenia in Tauris .

Trade relations with the Scythians led to the foundation of the first outposts between 750 and 500 BC during the Old Greek Diaspora. In the Eastern part of the Crimea the Bosporan kingdom was founded with Panticapaeum (modern Kerch) as its capital.

The Greeks had to fight off Scythian and Sarmatian (Alan) raiders who prevented them from progressing inland but retained the shores which became the wheat basket of the ancient Greek world. [2] Following the conquests of Alexander the Great and the Roman conquest the provinces maintained active trading relations with the interior for centuries. [2] [3]

Medieval

Black Sea trade became more important for Constantinople as Egypt and Syria were lost to Islam in the 7th century. Greek missionaries were sent among the steppe people, like the Alans and Khazars. Most notable were the Byzantine Greek monks Saints Cyril and Methodius from Thessalonica in Greek Macedonia, who later became known as the apostles of the Slavs.

Many Greeks remained in Crimea after the Bosporan kingdom fell to the Huns and the Goths, and Chersonesos became part of the Byzantine Empire. Orthodox monasteries continued to function, with strong links with the monasteries of Mount Athos in northern Greece. [2] [3]

Relations with the people from the Kievan Rus principalities were stormy at first, leading to several short lived conflicts, but gradually raiding turned to trading and many also joined the Byzantine military, becoming its finest soldiers. In 965 AD there were 16,000 Crimean Greeks in the joint Byzantine and Kievan Rus army which invaded Bulgaria.

Subsequently, Byzantine power in the Black Sea region waned, but ties between the two people were strengthened tremendously in cultural and political terms with the baptism of Prince Vladimir of Kievan Rus in 988 and the subsequent Christianization of his realm.

The post as Metropolitan bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church was, in fact, with few exceptions, held by a Byzantine Greek all the way to the 15th century. [2] [3] One notable such prelate was Isidore of Kiev.

Tsarist Russia

With the Fall of Constantinople in the 15th century, there was an exodus of Greeks to Italy and the West but especially to fellow-Christian Orthodox Russia. Between the fall of the Empire of Trebizond to the Ottomans in 1461 and the second Russo-Turkish War of 1828-29 there were several waves of refugee Pontic Greeks from the eastern Black Sea coastal districts, the Pontic Alps, and Eastern Anatolia to southern Russia and Georgia (see also Greeks in Georgia and Caucasus Greeks). Together with the marriage of Greek Princess Sophia and Tsar Ivan III of Russia, this provided a historical precedent for the Muscovite political theory of the Third Rome, positing Moscow as the legitimate successor to Rome and Byzantium.

Greeks continued to migrate in the following centuries. Many sought protection in a country with a culture and religion related to theirs. Greek clerics, soldiers and diplomats found employment in Russia and Ukraine while Greek merchants came to make use of privileges that were extended to them in Ottoman-Russian trade.

Under Catherine the Great, Russian armies reached the shores of the Black Sea, followed by the foundation of Odessa – greatly facilitating the settlement of Greeks, many thousands of whom were settled in the empire’s south under this empress. During the 1828-29 war against the Ottoman Empire and Russian occupation of Erzurum and Gümüşhane many thousands of Pontic Greeks of the highland regions of Eastern Anatolia welcomed or collaborated with the invading Russian imperial army. They followed the Russians back into southern Russia and Georgia following the withdrawal from northeastern Anatolia and were resettled by the Russian authorities in southern Georgia and southern Russia and Ukraine. These Greeks are often referred to as Russianized Pontic Greeks, while those of Georgia and the South Caucasus province of Kars Oblast are usually referred to as Caucasus Greeks.

There were over 500,000 Greeks in the Russian Empire prior to the Russian Revolution, between 150,000 and 200,000 of them within the borders of the present-day Russian Federation. [3]

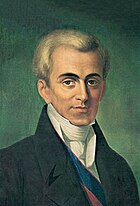

There have been several notable Greeks from Russia like Ioannis Kapodistrias, diplomat of the Russian Empire who became the first head of state of Greece, and the painter Arkhip Kuindzhi.

Soviet Union

In the early years after the October Revolution of 1917, there were contradictory trends in Soviet governmental policies towards ethnic Greeks. Greeks engaged in trade or other occupations that marked them as class enemies of the Bolshevik government - who constituted a large part of the whole - were exposed to a hostile attitude. [3] This was exacerbated due to the participation of a regiment from Greece, numbering 24,000 troops, in Crimea among the forces intervening on the White Russian side in the Civil War of 1919 [4]

About 50,000 Greeks emigrated between 1919 and 1924. After 1924 Soviet authorities pressed Greece to repatriate 70,000 Greeks from Russia, although few actually had ancestors who were citizens of the Greek state. [3]

On the other hand, as with other ethnic nationalities, the early Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin and his immediate successors were willing to encourage ethnic culture manifestations of those ready to work within the new revolutionary regime.

In this framework, a Rumaiic (Pontic Greek) revival occurred in the 1920s. The Soviet administration established a Greek-Rumaiic theater, several magazines and newspapers and a number of Rumaiic language schools. The best Rumaiic poet Georgi Kostoprav created a Rumaiic poetic language for his work. Promoting the Rumaiic, as against the Demotic Greek of Greece, was in effect a way of promoting the separate identity of Soviet Greeks versus Greeks in Greece and elsewhere outside the USSR. In the same spirit, A. A. Beletsky created a Cyrillic alphabet for Pontic in 1969. [5]

However, official promotion of the Rumaiic did not go unchallenged. In the Πανσυνδεσμιακή Σύσκεψη (All-Union Conference) of 1926, organized by the Greek-Russian intelligentsia, it was decided that demotic should be the official language of the community. [6]

Different sources referring to this period differ in putting the emphasis on the positive or the negative aspects of the 1920s Soviet policy.

The Greek Autonomous District in Southern Russia existed in years 1930-1939. Its capital was Krymskaya.

The policy underwent a sharp reversal in 1937. At the time of the Moscow Trials and the purges targeting various groups and individuals who aroused Joseph Stalin's often unbased suspicions, policies towards ethnic Greeks became unequivocally harsh and hostile. Kostoprav and many other Rumaiics and Urums were killed, and a large percentage of the population was detained and transported to Gulags or deported to remote parts of the Soviet Union.

Greek Orthodox churches, Greek-language schools and other cultural institutions were closed. During the "Grecheskaya Operatsiya" (Греческая Операция), i.e., Greek Operation [a] , launched on Stalin's orders in December 1937, there were mass arrests of Greeks, especially but not only wealthy and self-employed, affecting some 50,000 Greeks out of an overall community of 450,000.

In the immediate aftermath of the World War II German invasion of the Soviet Union, ethnic Greeks were included in the 1941–1942 "preventive" deportations of Soviet citizens of "enemy nationality", together with ethnic Germans, Finns, Romanians, Italians, and others - even though Greece fought on the Allied side. The Greeks then suffered under Nazi occupation and when Crimea was liberated in 1944, most of the Greeks were exiled to Kazakhstan, along with the Crimean Tatars. (Some of these Greeks, known as Urums, spoke a variant of the Crimean Tatar language as the mother tongue they adopted during centuries of life in proximity to the Tartars).

In a further wave, about 100,000 Pontic Greeks, including 37,000 in the Caucasus area alone, were deported to Central Asia in 1949 during Stalin's post-war deportations.

At about the same time, the last major immigration occurred in the opposite direction, of Greeks going to Russia and the Soviet Union. After the end of the Greek civil war the defeated Communist supporters became political refugees. Over 10,000 of them ended up in the Soviet Union. [7]

After the de-Stalinization, Greeks were gradually allowed to return to their homes in the Black Sea region. Many have emigrated to Greece since the early 1990s. [3]

A new attempt to preserve a sense of ethnic Rumaiic identity started in the mid-1980s. The Ukrainian scholar Andriy Biletsky created a new Slavonic alphabet but, though a number of writers and poets make use of this alphabet[ citation needed ], the population of the region rarely uses it. [8]

Present

| Part of a series on |

| Greeks |

|---|

|

| Etymology · Greek names |

| History of Greece |

Many Greeks in the Soviet Union sought to emigrate to Greece in the final years before the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In 1990, 22,500 Pontian Greeks left the Soviet Union, a dramatic increase from previous years. Figures for 1991 indicate that about 1,800 left every month, primarily from Central Asia and Georgia. [9]

Today most Greeks in the former USSR speak Russian, [10] [11] with a significant number speaking their traditional Pontic Greek. Pontian is a Greek dialect that derives from the ancient Ionic Greek dialect and resembles ancient Greek more than the modern "demotic" Greek language.

Until recently, the ban on teaching Greek in Soviet schools meant that Pontian was spoken only in a domestic context. Consequently, many Greeks, especially those of the younger generation, speak Russian as their first language. [11]

Linguistically, Greeks are far from being unified. In Ukraine alone, there are at least five documented Greek linguistic groups, which are broadly categorized as the "Mariupol dialect", a term derived from the city of Mariupol, a traditional center of this community. Other Greeks in the Crimea speak Tatar, and in regions such as Tsalka in Georgia there are numerous Turkophone Greeks. [11]

Greeks were permitted to teach their own language again during Perestroika, and a number of schools are now teaching Greek. Because of their strongly philhellenic sentiments and ambitions to live in Greece, this is normally modern, Demotic Greek rather than Pontian. [9]

Cosmonaut Fyodor Yurchikhin has Greek Ancestry.

Close to 35% of the Russian Greeks live in the Caucasian province of Stavropol Krai, mainly Caucasus Greeks and Pontic Greeks. The city of Yessentuki is regarded as the Greek cultural capital of Russia. Many of the famous Greek Russians, like Euclid Kyurdzidis hail from this city where Greeks constitute 5.7% (Up from 5.4% in 1989) of the total population. Greeks constitute 3% (2.9% in 1989) of the population in Zheleznovodsk City and 4.7% in Inozemtsevo (5.1% in 1989). But the majority of the Greeks live in the rural regions of Stavropol and major concentrations can be found in the rural districts of Andropovsky (3.3% in 2002, 2.1% in 1989), Mineralovodsky (3.8% in 2002, 3.4% in 1989) and Predgorny (16.0% in 2002, 12.2% in 1989). [12] While the ethnic Greek population decreased in many provinces due to emigration, in the Stavropol province it actually rose from 26,828 in 1989 to 34,078 in 2002. A significant ethnic Greek population also exists in nearby Krasnodar Krai.

Yanis Kanidis, a man who rescued children in the Beslan hostage crisis, was of Greek descent.

In recent years, many Russian émigrés of Greek descent who had left in the early 1990s have returned to Russia, often with their Greece-born children. The return emigration is largely due to the economic crisis that Greece has been experiencing since 2008.