| July 2009 Ürümqi riots | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Xinjiang conflict | ||||

Rioters besieging a bus in Tianshan, Ürümqi, attacking escaping Han passengers with sticks. | ||||

| Date | 5–8 July 2009 | |||

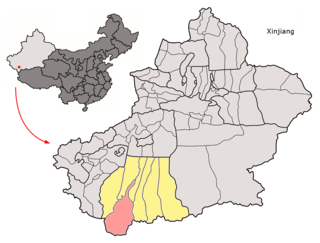

| Location | Ürümqi, Xinjiang, China | |||

| Caused by | Anger over the Shaoguan incident | |||

| Parties | ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

| Number | ||||

| ||||

| Casualties | ||||

| Death(s) | 197+ [6] [7] | |||

| Injuries | 1,721 [8] [9] | |||

| Arrested | 1,500+ [10] | |||

| Charged | 400+ [11] | |||

Xinjiang is a large central-Asian region within the People's Republic of China comprising numerous ethnic groups. Its two largest ethnic groups are the Uyghurs and Han, who make up 45 and 40 per cent of the population, respectively. [24] Its heavily industrialised capital, Ürümqi, has a population of more than 2.3 million, about 75 per cent of whom are Han, 12.8 per cent are Uyghur, and 10 per cent are from other ethnic groups. [24]

In general, Uyghurs and the Han-dominated government disagree on which group has greater historical claim to the Xinjiang region: Uyghurs believe their ancestors were indigenous to the area, whereas government policy considers present-day Xinjiang to have belonged to China since around 200 BC. [25] According to Chinese government policy, Uyghurs are classified as a National Minority rather than an indigenous group—in other words, they are considered to be no more indigenous to Xinjiang than the Han, and have no special rights to the land under the law. [25] The Chinese government has presided over the migration into Xinjiang of millions of Han, who dominate the region economically and politically. [26] [27] [28] [29]

During the Qing Dynasty, the Qianlong Emperor had ordered the genocide of Dzungar tribe to punish their leader Amursana for rebelling against Qing rule. After the genocide of Dzungar people, the Qing empire had sponsored Han, Hui, Uyghur, Xibe, and Kazakh colonists in settling into the region, which resulted in a major regional demographic change, with 62 percent Uyghurs concentrated in the southern Xinjiang's Tarim Basin, and around 30 percent Han and Hui people in the north. [30] [31] Professor Stanley W. Toops noted that today's demographic situation is similar to that of the early Qing period in Xinjiang. At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest of the area, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs. [32] A census of Xinjiang under Qing rule in the early 19th century tabulated ethnic shares of the population as 30% Han and 60% Turkic, while it dramatically shifted to 6% Han and 75% Uyghur in the 1953 census. However, the recorded population, which had increased to 18.64 million people, was 40.57% Han and 45.21% Uyghur by 2000. [33]

Although the Chinese government's minority policy, which is based on affirmative actions, has reinforced a Uyghur ethnic identity that is distinct from the Han population, [34] [35] some scholars argue that Beijing unofficially favours a monolingual, monocultural model that is based on the majority. [25] [36] The authorities also crack down on any activity that appears to constitute separatism. [35] [37] These policies, in addition to long-standing cultural differences, [38] have sometimes resulted in "resentments" between Uyghur and Han citizens. [39] On one hand, as a result of Han immigration and government policies, Uyghurs' freedoms of religion and of movement are curtailed, [40] [41] while most Uyghurs argue that the government downplays their history and traditional culture. [25] On the other hand, some Han citizens view Uyghurs as benefiting from special treatment, such as preferential admission to universities and exemption from the one-child policy, [42] and as "harbouring separatist aspirations". [43]

Tensions between Uyghurs and Han have resulted in waves of protest in recent years. [44] Xinjiang has been the location of several instances of violence and ethnic clashes, such as the Ghulja Incident of 1997, the 2008 Kashgar attack, widespread unrest preceding the Olympic Games in Beijing, as well as numerous minor attacks. [26] [45]

Immediate causes

The riots took place several days after a violent incident in Shaoguan, Guangdong, where many migrant workers are employed as part of a government programme to alleviate labour shortages. According to state media, a disgruntled former worker disseminated rumours in late June that two Han women had been raped by six Uyghur men. [15] [46] Official sources later said they found no evidence to support the rape allegation. [47] Overnight on 25–26 June, tensions at the Guangdong factory led to a full-blown ethnic brawl between Uyghur and Han workers, during which two Uyghurs were killed. [48] Exiled Uyghur leaders alleged the death toll was much higher. [49] While the official Xinhua News Agency reported that the person responsible for spreading the rumours had been arrested, Uyghurs alleged that the authorities had failed to protect the Uyghur workers, or to arrest any of the Han people involved in the killings. [49] They organised a street protest in Ürümqi on 5 July to voice their discontent [15] [16] and to demand a full government investigation. [50]

At some point the demonstration became violent. A government statement called the riots a "pre-empted, organised violent crime ... instigated and directed from abroad, and carried out by outlaws." [51] Nur Bekri, chairman of the Xinjiang regional government, said on 6 July that overseas separatist forces had taken advantage of the Shaoguan incident "to instigate the unrest [of 5 July] and undermine ethnic unity and social stability". [51] The government blamed the World Uyghur Congress (WUC), an international organisation of exiled Uyghur groups, for coordinating and instigating the riots over the internet. [51] Government sources blamed Kadeer in particular, citing her public speeches after the Tibetan unrest and phone recordings in which she had allegedly said that something would happen in Ürümqi. [52] Chinese authorities accused a man who they alleged to be a key WUC member of inciting ethnic tensions by circulating a violent video, and urging Uyghurs, in an online forum, to "fight back [against Han Chinese] with violence". [53] Jirla Isamuddin, the mayor of Ürümqi, claimed that the protesters had organised online via such services as QQ Groups. [54] China Daily asserted that the riots were organised to fuel separatism and to benefit Middle East terrorist organisations. [55] [56] Kadeer denied fomenting the violence, [17] and argued that the Ürümqi protests and their descent into violence were triggered by heavy policing, discontent over Shaoguan and "years of Chinese repression", rather than by the intervention of separatists or terrorists. [57] Uyghur exile groups claimed that violence erupted when police used excessive force to disperse the crowd. [2] [3]

All parties, then, agree that the protests were organised beforehand; the main points of contention are whether the violence was planned or spontaneous, [58] and whether the underlying tensions reflect separatist inclinations or a desire for social justice. [50]

Events

Initial demonstrations

Demonstrations began on the evening of 5 July with a protest in the Grand Bazaar, a prominent tourist site, [50] [4] and crowd reportedly gathering at the People's Square area. [59] The demonstration began peacefully, [16] [54] and official and eyewitness accounts reported that it involved about 1,000 Uyghurs; [12] [5] [60] the WUC said approximately 10,000 protesters took part. [12]

On 6 July, XUAR chairman Nur Bekri presented an official timeline of the previous day's events, according to which more than 200 demonstrators gathered in People's Square in Ürümqi at about 5 pm local time, and about 70 of their leaders were detained. Later, a crowd gathered in the mostly Uyghur areas of South Jiefang Road, Erdaoqiao, and Shanxi Alley; by 7:30 pm, more than one thousand were gathered in front of a hospital in Shanxi Alley. At about 7:40 pm, more than 300 people blocked the roads in the Renmin Road and Nanmen area. According to Bekri, rioters began to smash buses at 8:18 pm, after police "controlled and dispersed" the crowd. [61]

How the demonstrations became violent is unclear. [62] [63] [64] Some say the police used excessive force against the protesters; [62] [65] [66] the World Uyghur Congress quickly issued press releases saying that the police had used deadly force and killed "scores" of protesters. [67] [68] Kadeer has alleged that there were agents provocateurs among the crowds. [69] [70] Others claim that the protesters initiated the violence; for example, a Uyghur eyewitness cited by The New York Times said protesters began throwing rocks at the police. [15] The government's official line was that the violence was not only initiated by the protesters, but also had been premeditated and coordinated by Uyghur separatists abroad. [51] [54] The local public security bureau said it found evidence that many Uyghurs had travelled from other cities to gather for the riot, and that they had begun preparing weapons two or three days before the riot. [71]

Escalation and spread

After the confrontation with police turned violent, rioters began hurling rocks, smashing vehicles, breaking into shops and attacking Han civilians. [15] [2] At least 1,000 Uyghurs were involved in the rioting when it began, [12] [5] and the number of rioters may have risen to as many as 3,000. [1] Jane Macartney of The Times characterised the first day's rioting as consisting mainly of "Han stabbed by marauding gangs of [Uyghurs]"; [72] a report in The Australian several months later suggested that religiously moderate Uyghurs may also have been attacked by rioters. [21] Although the majority of rioters were Uyghur, not all Uyghurs were violent during the riots; there are accounts of Han and Uyghur civilians helping each other escape the violence and hide. [73] About 1,000 police officers were dispatched; they used batons, live ammunition, tasers, tear gas and water hoses to disperse the rioters and set up roadblocks and posted armoured vehicles throughout the city. [3] [4] [5] [62]

During a press conference, Mayor Jirla Isamuddin said that at about 8:15 pm, some protesters started to fight and loot, overturned guardrails and smashed three buses before being dispersed. [54] At 8:30 pm, violence escalated around South Jiefang Road and Longquan Street area, with rioters torching police patrol cars and attacking passers-by. [54] Soon, between 700 and 800 people went from the People's Square to Daximen and Xiaoximen area, "fighting, smashing, looting, torching and killing" along the way. At 9:30 pm, the government received reports that three people had been killed and 26 injured, six of whom were police officers. [54] Police reinforcements were dispatched to hotspots of Renmin Road, Nanmen, Tuanjie Road, Yan'An Road and South Xinhua Road. Police took control of the main roadways and commercial districts in the city at around 10 pm, but riots continued in side streets and alleyways, with Han civilians attacked and cars overturned or torched, according to the mayor. [54] Police then formed small teams and "swept" the entire city for the next two days. [54] A strict curfew was put in place; [74] authorities imposed "comprehensive traffic control" from 9:00 pm on 7 July to 8:00 am 8 July "to avoid further chaos". [75]

The official news agency, Xinhua, reported that police believed agitators were trying to organise more unrest in other areas in Xinjiang, such as Aksu and Yili Prefectures. [65] Violent protests also sprang up in Kashgar, in southwestern Xinjiang, [76] where the South China Morning Post reported many shops were closed, and the area around the mosque was sealed off by a People's Liberation Army platoon after confrontations. Local Uyghurs blamed the security forces for using excessive force –they "attacked the protesters and arrested 50 people". [77] Another clash was reported near the mosque on 7 July and an estimated 50 people were arrested. Up to 12,000 students at the Kashgar Teaching Institute were confined to campus after the 5 July riots, according to the Post. Many of the institute's students had apparently travelled to Ürümqi for the demonstrations there. [78]

Casualties and damage

During the first hours of the rioting, state media only reported that three people had been killed. [16] [3] [79] The number rose sharply, though, after the first night's rioting; at midday on 6 July, Xinhua announced that 129 people had died. [80] In the following days the death toll reported by various government sources (including Xinhua and party officials) gradually grew, with the last official update on 18 July placing the tally at 197 dead [6] [81] and 1,721 injured. [8] [9] The World Uyghur Congress has claimed that the death toll was around 600. [12]

Xinhua did not immediately disclose the ethnic breakdown of the dead, [76] but journalists from The Times and The Daily Telegraph reported that most of the victims appeared to have been Han. [40] [82] For instance, on 10 July Xinhua stated that 137 of the dead (out of the total of 184 that was being reported at that time) were Han, 46 Uyghur, and 1 Hui. [83] There were casualties among the rioters as well; [62] for example, according to official accounts, a group of 12 rioters attacking civilians were shot by police. [84] [85] In the months following the riots, the government maintained that the majority of casualties were Han [10] and hospitals said that two-thirds of the injured were Han, [2] although the World Uyghur Congress claims that many Uyghurs were killed as well. [10] According to the official count released by the Chinese government in August 2009, 134 of the 156 civilian victims were Han, 11 Hui, 10 Uyghur, and 1 Manchu. [86] Uyghur advocates continue to question these figures, saying that the number of ethnic Uyghurs remains understated. [63] Nevertheless, third-party sources confirm that most of the casualties were Han Chinese. [23] [87] [88] Xinhua News Agency reported that 627 vehicles and 633 constructions were damaged. [89]

The Ürümqi municipal government initially announced that it would pay ¥200,000 as compensation, plus another ¥10,000 as "funeral expense" for every "innocent death" caused by the riot. [90] The compensation was later doubled to ¥420,000 per death. [91] Mayor Jirla Isamuddin estimated that the compensations would cost at least ¥100 million. [90]

After 5 July

The city remained tense while journalists invited into the city witnessed confrontational scenes between Chinese troops and Uyghurs demanding the release of family members who they said had been arbitrarily arrested. [72] Uyghur women told The Daily Telegraph reporter that police entered Uyghur districts in the night of 6 July, burst through doors, pulled men and boys from their beds, and rounded up 100 suspects. [92] By 7 July, officials reported that 1,434 suspected rioters had been arrested. [93] A group of 200 to 300 Uyghur women assembled on 7 July to protest what they said was "indiscriminate" detention of Uyghur men; the protest led to a tense but non-violent confrontation with police forces. [94] [95] Kadeer claimed that "nearly 10,000 people" had gone missing overnight. [96] Human Rights Watch later documented 43 cases of Uyghur men who disappeared after being taken away by Chinese security forces in large-scale sweeps of Uyghur neighbourhoods overnight on 6–7 July, [63] and said that this was likely to be "just the tip of the iceberg". [14] Human Rights Watch alleges that young men, mostly in their 20s, had been unlawfully arrested and have not been seen or heard from as of 20 October 2009. [63]

On 7 July, there were large-scale armed demonstrations [97] by ethnic Han in Ürümqi. [98] Conflicting estimates of the Han demonstrators' numbers were reported by the western media and varied from "hundreds" [97] to as high as 10,000. [98] The Times reported that smaller fights were frequently breaking out between Uyghurs and Han, and that groups of Han citizens had organised to take revenge on "Uyghur mobs". [72] [98] Police used tear gas and roadblocks in an attempt to disperse the demonstration, [99] and urged Han citizens over loudspeakers to "calm down" and "let the police do their job". [98] Li Zhi, party secretary of Ürümqi, stood on the roof of a police car with a megaphone appealing to the crowd to go home. [92]

Mass protests had been quelled by 8 July, although sporadic violence was reported. [100] [101] [102] In the days after the riots, "thousands" of people tried to leave the city, and the price for bus tickets rose as much as fivefold. [19] [103]

On 10 July, city authorities closed Ürümqi mosques "for public safety", saying it was too dangerous to have large gatherings and that holding Jumu'ah , traditional Friday prayers, could reignite tensions. [19] [104] Large crowds of Uyghurs gathered for prayer anyway, however, and police decided to let two mosques open to avoid having an "incident". [19] After prayers at the White Mosque, several hundred people demonstrated over people detained after the riot, [105] [106] but were dispersed by riot police, with five or six people arrested. [105]

Over 300 more people were reported arrested in early August. According to the BBC, the total number of arrests in connection with the riots was over 1,500. [10] The Financial Times estimated that the number was higher, citing an insider saying that some 4,000 arrests had already taken place by mid July, and that Ürümqi's prisons were so full that newly arrested people were being held in a People's Liberation Army warehouse. [107] According to the Uyghur American Association, several other Uyghur journalists and bloggers were also detained after the riots; one of them, journalist Gheyret Niyaz, was later sentenced to 15 years in prison for having spoken to foreign media. [108] In the most high-profile case, Ilham Tohti, an ethnic Uyghur economist at Minzu University of China, was arrested two days after the riots over his criticisms of the Xinjiang government. [109] [110] [111]

Reactions and response

Domestic reaction

Communications black-out

Mobile phone service and internet access were limited both during and after the riots. China Mobile phone service was cut "to prevent the incident from spreading further". [112] Outbound international calls throughout Xinjiang were blocked, [113] [114] and Internet connections in the region had been locked down [115] [116] or non-local websites blocked. Reporting from Ürümqi's Hoi Tak Hotel on 9 July, Al Jazeera reported that the foreign journalists' hotel was the only place in the city with Internet access, although the journalist could not send text messages or place international phone calls. [114] Many unauthorised postings on local sites and Google were removed by censors; [63] images and video footage of the demonstrations and rioting, however, were soon found posted on Twitter, YouTube, and Flickr. [117] Many Xinjiang-based websites became inaccessible worldwide, [49] and internet access within Ürümqi remained restricted nearly a year following the riots; [118] it was not restored until 14 May 2010. [119]

Government

Chinese state-controlled television broadcast graphic footage of cars being smashed and people being beaten. [120] Officials reiterated the party line: XUAR chairman Nur Bekri delivered a lengthy address on the situation and on the Shaoguan incident, and claimed that the government of both Guangdong and Xinjiang had dealt with the deaths of the workers properly and with respect. Bekri further condemned the riots as "premeditated and planned"; [121] Eligen Imibakhi, chairman of the Standing Committee of the Xinjiang Regional People's Congress, blamed 5 July riots on "extremism, separatism and terrorism". [122] [123]

Chinese media covered the rioting extensively. [18] Hours after troops stopped the rioting, the state invited foreign journalists on an official fact-finding trip to Ürümqi; [124] journalists from more than 100 media organisations were all corralled into the downtown Hoi Tak Hotel, [113] [114] sharing 30 internet connections. [113] Journalists were given unprecedented access to troublespots and hospitals. [125] The Financial Times referred to this handling as an improvement, compared to the "public-relations disaster" of the Tibetan unrest in 2008. [18]

In an effort to soothe tensions immediately after the riots, state media began a mass publicity campaign throughout Xinjiang extolling ethnic harmony. Local television programmes united Uyghur and Han singers in a chorus of "We are all part of the same family"; Uyghurs who "acted heroically" during the riots were profiled; loud-hailer trucks blasted slogans in the streets. A common slogan warned against the "Three Evils": terrorism, separatism and extremism. [126]

Chinese President and General Secretary of the Communist Party Hu Jintao curtailed his attendance of the G8 summit in Italy, [74] [127] convened an emergency meeting of the Politburo, and dispatched Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang to Xinjiang to "guid[e] stability-preservation work in Xinjiang". [128] South China Morning Post reported a government source saying Beijing would re-evaluate the impact on arrangements for the country's forthcoming 60th anniversary celebrations in October. [129] Guangdong's CPC Provincial Committee Secretary, Wang Yang, noted that the government policies towards ethnic minorities "definitely need adjustments", otherwise "there will be some problems." [130] A security planner said the authorities planned to fly in more troops from other stations to raise the number of armed police presence to 130,000 before the 60th anniversary celebrations in October. [107]

After the riots, the Chinese government exercised diplomatic pressure on nations that Kadeer was scheduled to visit. In late July, India declined Kadeer a visa "on the advice of Beijing", [131] and Beijing summoned the Japanese ambassador in protest of a trip Kadeer made to Japan. [132] [133] When Kadeer visited Australia in August to promote a film about her life, China officially complained to the Australian government and asked for the film to be withdrawn. [133]

Internet response

The response to the riots on the Chinese blogosphere was markedly more varied than the official response. Despite blocks and censorship, Internet watchers monitored continued attempts by netizens to publish their own thoughts on the causes of the incident or vent their anger about the violence. While some bloggers were supportive of the government, others were more reflective of the event's cause. [134] On numerous forums and news sites, government workers quickly removed comments about the riots. [134] [135] Common themes were calls for punishment for those responsible; some posts evoked the name of Wang Zhen, a 20th century general who is respected by the Han but feared by many Uyghurs for his repression in Xinjiang after the communist takeover of the region in 1949. [134]

International reactions

Intergovernmental organisations

- United Nations: Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon urged all sides to exercise restraint, [136] and called on China to take measures to protect the civilian population as well as respect the freedoms of citizens, including freedom of speech, assembly and information. [137] Human rights chief Navi Pillay said she was "alarmed" over the high death toll, noting this was an "extraordinarily high number of people to be killed and injured in less than a day of rioting." [138] [139] She also said China must treat detainees humanely in a way that adheres to international norms. [140]

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation : said it sympathised with the family members of those innocent people killed in the riot; it said that its member states regard Xinjiang as an inalienable part of the People's Republic of China and believe the situation in Xinjiang is purely China's internal affairs. [141] Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov condemned rioters for "Using separatist slogans and provoking ethnic intolerance. [142] Officials from both neighbouring Kazakhstan [143] and Kyrgyzstan said they were braced for "an influx of refugees" and tightened border controls. [144] [145] Despite the Kazakh government support, over 5,000 Uyghurs protested on 19 July in former capital Almaty against Chinese police use of deadly force against the rioters. [146]

- Organisation of the Islamic Conference : decried the "disproportionate use of force", calling on the Chinese government to "bring those responsible to justice swiftly" and urging China to find a solution to the unrest by examining why it had erupted. [147]

- European Union : leaders expressed concern, and urged the Chinese government to show restraint in dealing with the protests: [148] [149] German Chancellor Angela Merkel urged respect for the rights of minorities; [150] Italian President Giorgio Napolitano brought up human rights at a press conference with Hu Jintao, and said that "economic and social progress that is being achieved in China places new demands in terms of human rights." [151] [152]

Countries

Turkey, a Turkic-majority country with a significant Uyghur minority, officially expressed "deep sadness" and urged the Chinese authorities to bring the perpetrators to justice. [153] [154] Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said the incident was "like genocide", [155] [156] while Turkish Trade and Industry Minister Nihat Ergün unsuccessfully called for a boycott on Chinese goods. [157] [158] [159] Several protests against the Chinese government's response to the riots also occurred in front of Chinese embassies and consulates in Turkey. The Turkish government's stance sparked a significant outcry from Chinese media. [160] [161] [162]

Afghanistan, [163] Cambodia [164] and Vietnam said they believed the Chinese government was "taking appropriate measures," [165] and their statements backed "the territorial integrity and sovereignty of China." [163] Micronesian Vice-president Alik Alik condemned the riots as a "terrorist act." [166]

Iran said it shared the concerns of Turkey and the OIC and appealed to the Chinese government to respect the rights of the Muslim population in Xinjiang. [167]

Japan stated that it was monitoring the situation with concern; [168] Singapore urged restraint and dialogue; [169] while Taiwan strongly condemned all those who instigated the violence. Taiwanese premier Liu Chiao-shiuan also urged restraint and expressed hope that the Chinese authorities will demonstrate the "greatest possible leniency and tolerance in dealing with the aftermath" and respect the rights of ethnic minorities. [170] Taiwan denied a visa to Kadeer in September 2009, alleging she had links to the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, classed as a terrorist organisation by the United Nations and United States. [171]

Switzerland called for restraint, and sent condolences to the families of victims and urged China to respect freedom of expression and the press. [172] Prime Minister Kevin Rudd of Australia urged restraint to bring about a "peaceful settlement to this difficulty." [150] Serbia stated that it opposed separatism and supports the "resolution of all disputes by peaceful means." [173] Belarus noted with regret the loss of life and damage in the region, and hoped that the situation would soon normalise. [174]

There was violence in the Netherlands and in Norway. The Chinese embassy in the Netherlands was attacked by Uyghur activists who smashed windows with bricks [99] and burned Chinese flags. [175] There were 142 arrests, [176] and the embassy was closed for the day. [177] About 100 Uyghurs protested outside the Chinese embassy in the Norwegian capital Oslo. Eleven were detained and later released without charges. [178] Protesters from a coalition of Indonesian Islamist groups attacked guards at the Chinese embassy in Jakarta and called for a jihad against China. [179] Pakistan said that certain "elements" were out to harm China-Pakistan relations, but they would not succeed in destabilising the interests of the two countries. [180] Sri Lanka stressed the incident was an internal affair of China and was confident that efforts by the Chinese authorities would restore normalcy. [181]

Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Lawrence Cannon urged "dialogue and goodwill" to help resolve grievances and prevent further deterioration of the situation. [182] A U.S. government spokesman said the U.S. regretted the loss of life in Xinjiang, [148] was deeply concerned and called on all sides to exercise restraint. [136] U.S. State Department spokesman Ian Kelly, said "it's important that the Chinese authorities act to restore order and prevent further violence." [183] The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom expressed "grave concern" over repression in China and called for an independent investigation on the riots and targeted sanctions against China. [184]

Non-governmental organisations

- Amnesty International : called for an "impartial and independent" inquiry into the incident, adding that those detained for "peacefully expressing their views and exercising their freedom of expression, association and assembly" must be released and others ensured to receive a fair trial. [185]

- Human Rights Watch : urged China to exercise restraint and to allow an independent inquiry into the events, which would include addressing Uyghur concerns about policies in the region. It also added that China should respect international norms when responding to the protests and only use force proportionately. [186]

- Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb : called on its supporters to attack Chinese workers in North Africa. [187] [188] [189]

Media coverage

Chen Shirong, China editor on the BBC World Service, remarked at the improvement in media management by Xinhua: "To be more credible, it released video footage a few hours after the event, not two weeks." [190] Peter Foster of the Daily Telegraph observed that "long-standing China commentators have been astonished at the speed at which Beijing has moved to seize the news agenda on this event," and attributed it to his belief that "China doesn't have a great deal to hide". [125] A University of California, Berkeley academic agreed that the Chinese authorities had become more sophisticated. [124] The New York Times and AFP recognised the Chinese learnt lessons from political protests around the world, such as the so-called colour revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine, and the 2009 Iranian election protests, and concluded that Chinese experts had studied how modern electronic communications "helped protesters organize and reach the outside world, and for ways that governments sought to counter them." [124] [191]

But Willy Lam, fellow of the Jamestown Foundation, sceptically said that the authorities were "just testing the reaction". He believed that if the outcome of this openness was poor they would "put the brakes on" as they did after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. [191] There were instances of foreign journalists being taken into custody by the police, to be released shortly thereafter. [63] On 10 July, officials ordered foreign media out of Kashgar, "for their own safety." [192] Xia Lin, a top official at Xinhua, later revealed that violence caused by both sides during and after the riots had been downplayed or wholly unreported in official news channels, for the fear that the ethnic violence would spread beyond Ürümqi. [193]

A People's Daily op-ed rebuked certain western media outlets for their "double standards, biased coverage and comments". It said that China failed to receive fair "repayment" from certain foreign political figures or media outlets for its openness and transparent attitude. The author said "a considerable number of media outlets still intentionally or inadvertently minimised the violent actions of the rioters, and attempted to focus on so-called racial conflict." [194] However, D'Arcy Doran from Agence France-Presse welcomed the increased openness for foreign media, but contrasted their reporting to Chinese media, which closely followed the government line to focus mainly on injured Han civilians whilst ignoring the "Uyghur story" or reasons behind the incident. [191]

Many early reports of the riots, starting with one from Reuters, used a picture purporting to show the previous day's riots. [195] The photo, showing large number of People's Armed Police squares, was one taken of the 2009 Shishou riot and originally published on 26 June by Southern Metropolis Weekly. [196] The same picture was mistakenly used by other agencies; [197] it was on the website of The Daily Telegraph, but was removed a day later. [195] In an interview with Al Jazeera on 7 July, WUC leader Rebiya Kadeer used the same Shishou photograph to defend the Uyghurs in Ürümqi. [198] A World Uyghur Congress representative later apologised, explaining that the photo was chosen out of hundreds for its image quality. [197]

On 3 August, Xinhua reported that two of Rebiya Kadeer's children had written letters blaming her for orchestrating the riots. [199] A Germany-based spokesman for the WUC rejected the letters as fakes. A Human Rights Watch researcher remarked their style was "suspiciously close" to the way the Chinese authorities had described rioting in Xinjiang and the aftermath. He added that "it's highly irregular for [her children] to be placed on the platform of a government mouthpiece ... for wide dispersion." [200]

Aftermath and long-term impact

Arrests and trials

In early August, the Ürümqi government announced that 83 individuals had been "officially" arrested in connection with the riots. [201] China Daily reported in late August that over 200 people were being charged and that trials would begin by the end of August. [202] [203] Although this was denied both by a provincial and a local Party official, [9] Xinjiang authorities later announced that arrest warrants had been issued to 196 suspects, of which 51 had already been prosecuted. Police also requested that the procuratorate approve the arrest of a further 239 people, and detention of 825 more, China Daily said. [204] In early December, 94 "fugitives" were arrested. [205]

The state first announced criminal charges against detainees in late September, when it charged 21 people with "murder, arson, robbery, and damaging property". [206] 14,000 security personnel were deployed in Ürümqi from 11 October, and the next day a Xinjiang court sentenced six men to death, and one to life imprisonment, [207] for their roles in the riots. All six men were Uyghurs, and were found guilty of murder, arson and robbery during the riots. Foreign media said the sentences appeared to be aimed at mollifying the anger of the Han majority; [208] [209] the WUC denounced the verdict as "political", and said there was no desire to see justice served. [208] Human Rights Watch said that there were "serious violations of due process" at the trials of 21 defendants relating to July protests. It said the trials "did not meet minimum international standards of due process and fair trials" – specifically, it said that the trials were carried out in a single day without prior public notice, that the defendants' choice of lawyers was restricted, and that the Party had given judges instructions on how to handle the cases. [210] Xinhua, on the other hand, noted that the proceedings were conducted in both the Chinese and Uyghur languages, and that evidence had been carefully collected and verified before any decisions were made. [207]

By February 2010, the number of death sentences issued had increased to at least 26, [23] including at least one Han and one female Uyghur. [11] [211] Nine of the individuals sentenced were executed in November 2009; based on previous government statements, eight were Uyghur and one was Han. [22] [212]

Later unrest and security measures

Starting in mid-August, there was a string of attacks in which as many as 476 individuals may have been stabbed with hypodermic needles. [213] [214] Officials believed that the attacks were targeting Han civilians and had been perpetrated by Uyghur separatists. [215] In response to both concern over the attacks [216] and dissatisfaction over the government's slowness in prosecuting people involved with the July riots, thousands of Han protested in the streets. [217] On 3 September, five people died during the protests and 14 were injured, according to an official. [218] [219] The next day, the Communist Party secretary of Ürümqi, Li Zhi, was removed from his post, along with the police chief, Liu Yaohua; [220] the provincial Party secretary Wang Lequan was replaced in April 2010. [221]

While the city became calmer after these events, and the government made great efforts to show that life was returning to normal, an armed police presence did remain. As late as January 2010, it was reported that police were making patrols five or six times a day, and that patrols were stepped up at night. [21] Shortly before the first anniversary of the rioting, the authorities installed more than 40,000 surveillance cameras around Ürümqi to "ensure security in key public places". [222]

Legislation and investigation

In late August, the central government passed a law outlining standards for the deployment of armed police during "rebellion, riots, large-scale serious criminal violence, terror attacks and other social safety incidents." [223] [224] After the protests in early September, the government issued an announcement banning all "unlicensed marches, demonstrations and mass protests". [225] The provincial government also passed legislation banning the use of the internet to incite ethnic separatism. [118]

In November, the Chinese government dispatched some 400 officials to Xinjiang, including senior leaders such as State Council secretary general Ma Kai, Propaganda department head Liu Yunshan, and United Front chief Du Qinglin, to form an ad hoc "Team of Investigation and Research" on Xinjiang, ostensibly intended on studying the policy changes to be implemented in response to the violence. [226] In April 2010, party secretary Wang Lequan was replaced by Zhang Chunxian, a more conciliatory figure. [227] The government authorised transfer payments totalling some $15 billion from eastern provinces to Xinjiang to aid in the province's economic development, and announced plans to establish a special economic zone in Kashgar. [227]

China has installed a grassroots network of officials throughout Xinjiang, its predominantly Muslim north-west frontier region, to address social risks and spot early signs of unrest: Hundreds of cadres have been transferred from southern Xinjiang, the region's poorest area, into socially unstable neighbourhoods of Ürümqi. A policy has been implemented where if all family members are unemployed, the government arranges for one person in the household to get a job; official announcements are calling upon university students to register for those payouts. The areas around slums are being redeveloped to reduce social risks, opening way to new apartment blocks. [228] However, independent observers believe that fundamental inequalities need to be addressed, and the mindset must change for there to be any success; Ilham Tohti warned that the new policy could attract more Han immigration, and further alienate the Uyghur population. [229]

Public services and Internet access

It took until at least early August for public transport to be fully restored in the city. According to Xinhua, 267 buses had been damaged during the rioting; [230] most were back in operation by 12 August. [231] The government paid bus companies a total of ¥5.25 million in compensation. [230] Despite the resumption of transportation services, and the government's efforts to encourage visitors to the region, tourism fell sharply after the riots; [21] on the National Day holiday in October, Xinjiang had 25% fewer tourists than it did in 2008. [232]

Ürümqi public schools opened on schedule in September for the fall semester, but with armed police guarding them. Many schools began first-day classes by focusing on patriotism. [233]

On the other hand, Internet and international telephone service in Ürümqi remained limited for nearly a year after the riots. As late as November, most of the Internet was still inaccessible to residents and international phone calls were impossible; [118] as late as December, most web content hosted outside the region remained off-limits to all but a few journalists, [234] and residents had to travel to Dunhuang 14 hours away to access the Internet normally. Within the city, only about 100 local sites, such as banks and regional government websites, could be accessed. [118] Both incoming and outgoing international phone calls were disallowed, so Ürümqi residents could only communicate by calling intermediaries in other cities in China who would then place the international calls. [118] The communications blackout generated controversy even within China: Yu Xiaofeng of Zhejiang University criticised the move, and many Ürümqi locals said it hurt businesses and delayed recovery, whereas David Gosset of the Euro-China forum argued that the government had the right to shut down communications for the sake of social stability; some locals believed that getting away from the Internet even improved their quality of life. [118]

In late December, the government began restoring services gradually. The websites for Xinhua and the People's Daily, two state-controlled media outlets, were made accessible on 28 December, the web portals Sina.com and Sohu.com on 10 January 2010, [235] and 27 more websites on 6 February. [236] [237] But access to websites was only partial: for instance, users could browse forums and blogs but not post on them. [236] China Daily reported that limited e-mail services were also restored in Ürümqi on 8 February, although a BBC reporter writing at approximately the same time said e-mail was not accessible yet. [238] Text messaging on cell phones was restored on 17 January, although there was a limit to how many messages a user could send daily. [239] [240] Internet access was fully restored in May 2010. [119]

See also

Related Research Articles

Ürümqi is the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in Northwestern China. With a census population of 4 million in 2020, Ürümqi is the second-largest city in China's northwestern interior after Xi'an, as well as the largest in Central Asia in terms of population. Ürümqi has seen significant economic development since the 1990s and currently serves as a regional transport node and a cultural, political and commercial center.

Rebiya Kadeer is an ethnic Uyghur Chinese businesswoman and political activist. Born in Altay City, Xinjiang,China Kadeer became a millionaire in the 1980s through her real estate holdings and ownership of a multinational conglomerate. Kadeer held various positions in the National People's Congress in Beijing and other political institutions before being arrested in 1999 for, according to Chinese state media, sending confidential internal reference reports to her husband, who worked in the United States as a pro-East Turkistan independence broadcaster. After she fled to the United States in 2005 on compassionate release, Kadeer assumed leadership positions in overseas Uyghur organizations such as the World Uyghur Congress.

The Uyghur American Association is a prominent Uyghur American non-profit advocacy organization based in Washington, D. C. in the United States. It was established in 1998 by a group of Uyghur overseas activists to raise the public awareness of the Uyghur people, who primarily reside in Xinjiang, China, also known as East Turkestan. The Uyghur American Association is an affiliate organization of the World Uyghur Congress and works to promote the Uyghur culture and improved human rights conditions for Uyghurs.

Terrorism in China refers to the use of terrorism to cause a political or ideological change in the People's Republic of China. The definition of terrorism differs among scholars, between international and national bodies, and across time—there is no internationally legally binding definition. In the cultural setting of China, the term is relatively new and ambiguous.

The 2008 Uyghur unrest is a loose name for incidents of communal violence by Uyghur people in Hotan and Qaraqash county of Western China, with incidents in March, April, and August 2008. The protests were spurred by the death in police custody of Mutallip Hajim.

The 2008 Kashgar attack occurred on the morning of 4 August 2008, in the city of Kashgar in the Western Chinese province of Xinjiang. According to Chinese government sources, it was a terrorist attack perpetrated by two men with suspected ties to the Uyghur separatist movement. The men reportedly drove a truck into a group of jogging police officers, and proceeded to attack them with grenades and machetes, resulting in the death of 16 officers.

The Ghulja, Gulja, or Yining incident was the culmination of the Ghulja protests of 1997, a series of demonstrations in the city of Yining—known as Ghulja in Uyghur—in the Xinjiang autonomous region of China.

The World Uyghur Congress (WUC) is a US funded international organization of exiled Uyghur groups that claims to "represent the collective interest of the Uyghur people" both inside and outside of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. The World Uyghur Congress claims to be a nonviolent and peaceful movement that opposes what it considers to be the Chinese occupation of East Turkestan (Xinjiang) and advocates rejection of totalitarianism, religious intolerance and terrorism as an instrument of policy. It has been called the "largest representative body of Uyghurs around the world" and uses more moderate methods of human rights advocacy to influence the Chinese government within the international community in contrast to more radical Uyghur organizations.

The Shaoguan incident was a civil disturbance which took place overnight on 25–26 June 2009 in Guangdong, China. A violent dispute erupted between migrant Uyghurs and Han Chinese workers at a toy factory in Shaoguan as a result of false allegations of the sexual assault of a Han Chinese woman. Groups of Han Chinese set upon Uyghur co-workers, leading to at least two Uyghurs being violently killed by angry Han Chinese men, and some 118 people injured, most of them Uyghurs.

Ilham Tohti is a Uyghur economist serving a life sentence in China, on separatism-related charges. He is a vocal advocate for the implementation of regional autonomy laws in China, was the host of Uyghur Online, a website founded in 2006 that discusses Uyghur issues, and is known for his research on Uyghur-Han relations. Ilham was summoned from his Beijing home and detained shortly after the July 2009 Ürümqi riots by the authorities because of his criticism of the Chinese government's policies toward Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Ilham was released on August 23 after international pressure and condemnation. He was arrested again in January 2014 and imprisoned after a two-day trial. For his work in the face of adversity he was awarded the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award (2014), the Martin Ennals Award (2016), the Václav Havel Human Rights Prize (2019), and the Sakharov Prize (2019). Ilham is viewed as a moderate and believes that Xinjiang should be granted autonomy according to democratic principles.

In September 2009, Ürümqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China, experienced a period of unrest in the aftermath of the July 2009 Ürümqi riots. Late August and early September saw a series of syringe attacks on civilians. In response to the attacks, thousands of residents held protests for several days, resulting in the deaths of five people. In addition, the arrest and beating of several Hong Kong journalists during the protests attracted international attention.

The 2010 Aksu bombing was a bombing in Aksu, Xinjiang, People's Republic of China that resulted in at least seven deaths and fourteen injuries when a Uyghur man detonated explosives in a crowd of police and paramilitary guards at about 10:30 on 19 August, using a three-wheeled vehicle. The assailant targeted police officers in the area, and most of the victims were also Uyghurs. Xinhua news agency reported that six people were involved in the attack, and two had died; the other four were detained by police.

The 2011 Hotan attack was a bomb-and-knife attack that occurred in Hotan, Xinjiang, China on 18 July 2011. According to witnesses, the assailants were a group of 18 young Uyghur men who opposed the local government's campaign against the burqa, which had grown popular among older Hotan women in 2009 but were also used in a series of violent crimes. The men occupied a police station on Nuerbage Street at noon, killing two security guards with knives and bombs and taking eight hostages. The attackers then yelled religious slogans, including ones associated with Jihadism, as they replaced the Chinese flag on top of a police station with another flag, the identity of which is disputed.

The 2011 Kashgar attacks were a series of knife and bomb attacks in Kashgar, Xinjiang, China on July 30 and 31, 2011. On July 30, two Uyghur men hijacked a truck, killed its driver, and drove into a crowd of pedestrians. They got out of the truck and stabbed six people to death and injured 27 others. One of the attackers was killed by the crowd; the other was brought into custody. On July 31, a chain of two explosions started a fire at a downtown restaurant. A group of armed Uyghur men killed two people inside of the restaurant and four people outside, injuring 15 other people. Police shot five suspects dead, detained four, and killed two others who initially escaped arrest.

The 1989 Ürümqi unrest, also known as the 19 May riots in Ürümqi took place in the city of Ürümqi in May 1989, which began with Muslim protesters marched and finally escalated into violent attack against a Xinjiang Chinese Communist Party (CCP) office tower at People's Square on 19 May 1989. The protesters participating included Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other Turkic People.

The Xinjiang conflict, also known as the East Turkistan conflict, Uyghur–Chinese conflict or Sino-East Turkistan conflict, is an ethnic geopolitical conflict in what is now China's far-northwest autonomous region of Xinjiang, also known as East Turkistan. It is centred around the Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group who constitute a plurality of the region's population.

On 26 June 2013, rioting broke out in Shanshan County, in the autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. 35 people died in the riots, including 22 civilians, two police officers and eleven attackers.

On the early morning of Wednesday, 30 July 2014, Juma Tahir, the imam of China's largest mosque, the Id Kah Mosque in northwestern Kashgar, was stabbed to death by three young male Uyghur extremists. Religious leaders across denominations condemned the attack.

In May 2014, the Government of the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched the "Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism" in the far west province of Xinjiang. It is an aspect of the Xinjiang conflict, the ongoing struggle by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chinese government to manage the ethnically diverse and tumultuous province. According to critics, the CCP and the Chinese government have used the global "war on terrorism" of the 2000s to frame separatist and ethnic unrest as acts of Islamist terrorism to legitimize its counter-insurgency policies in Xinjiang. Chinese officials have maintained that the campaign is essential for national security purposes.

Since 2014, the Chinese government has committed a series of ongoing human rights abuses against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim minorities in Xinjiang which has often been characterized as persecution or as genocide. There have been reports of mass arbitrary arrests and detention, torture, mass surveillance, cultural and religious persecution, family separation, forced labor, sexual violence, and violations of reproductive rights.

References

- 1 2 3 Macartney, Jane (5 July 2009). "China in deadly crackdown after Uighurs go on rampage". The Times . London. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Elegant, Simon; Ramzy, Austin (20 July 2009). "China's War in the West". Time. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Barriaux, Marianne (5 July 2009). "Three die during riots in China's Xinjiang region: state media". The Sydney Morning Herald . Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 Branigan, Tania; Watts, Jonathan (5 July 2009). "Muslim Uighurs riot as ethnic tensions rise in China". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Agencies (5 July 2009). "Civilians die in China riots". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- 1 2 Hu Yinan, Lei Xiaoxun (18 July 2009). "Urumqi riot handled 'decisively, properly'". China Daily. Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- 1 2 Yan Hao, Geng Ruibin and Yuan Ye (18 July 2009). "Xinjiang riot hits regional anti-terror nerve". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Initial probe completed and arrest warrants to be issued soon, Xinjiang prosecutor says". South China Morning Post. Associated Press. 17 July 2009. p. A7.

- 1 2 3 Wong, Edward (25 August 2009). "Chinese President Visits Volatile Xinjiang". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Xinjiang arrests 'now over 1,500'". BBC News . 3 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 Cui Jia (5 December 2009). "Riot woman sentenced to death for killing". China Daily . Archived from the original on 15 December 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Scores killed in China protests". BBC News . 6 July 2009. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ Riley, Ann (21 October 2009). "China officials 'disappeared' Uighurs after Xinjiang riots: HRW". Paper Chase Newsburst. University of Pittsburgh School of Law. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- 1 2 Bristow, Michael (21 October 2009). "Many 'missing' after China riots". BBC News . Archived from the original on 26 November 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wong, Edward (5 July 2009). "Riots in Western China Amid Ethnic Tension". The New York Times . Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "China calls Xinjiang riot a plot against its rule". Reuters . 5 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- 1 2 "Profile: Rebiya Kadeer". BBC News . 8 July 2009. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 McGregor, Richard (7 July 2009). "Beijing handles political management of riots" . Financial Times . Archived from the original on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Some Urumqi mosques defy shutdown". BBC News . 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ "Internet Service In China's Xinjiang Will Soon Recover". China Tech News. 31 December 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Sainsbury, Michael (2 January 2010). "The violence has ended in Urumqi but shadows remain in hearts and minds". The Australian. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Nine executed over Xinjiang riots". BBC News . 9 November 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 Le, Yu (26 January 2010). "China sentences four more to death for Urumqi riot". Reuters . Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- 1 2 2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料,民族出版社[Year 2000 China census materials: Ethnic groups population]. Minzu Publishing House. September 2003. ISBN 7-105-05425-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Gladney, Dru C. (2004). "The Chinese Program of Development and Control, 1978–2001". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-0-7656-1318-9.

- 1 2 Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (16 February 2000). "Uyghur "separatism": China's policies in Xinjiang fuel dissent". Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Analyst. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Jiang, Wenran (6 July 2009). "New Frontier, same problems". The Globe and Mail. p. parag. 10. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

But just as in Tibet, the local population has viewed the increasing unequal distribution of wealth and income between China's coastal and inland regions, and between urban and rural areas, with an additional ethnic dimension. Most are not separatists, but they perceive that most of the economic opportunities in their homeland are taken by the Han Chinese, who are often better educated, better connected, and more resourceful. The Uyghurs also resent discrimination against their people by the Han, both in Xinjiang and elsewhere.

- ↑ Ramzy, Austin (14 July 2009). "Why the Uighurs feel left out of China's boom". Time. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ Larson, Christina (9 July 2009). "How China Wins and Loses Xinjiang". Foreign Policy . Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ ed. Starr 2004 Archived 9 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine , p. 243.

- ↑ Starr, S. Frederick (15 March 2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3192-3.

- ↑ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads: A history of Xinjiang. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3. p. 306

- ↑ Toops, Stanley (May 2004). "Demographics and Development in Xinjiang after 1949" (PDF). East-West Center Washington Working Papers (1). East–West Center: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ Bovingdon, Gardner (2005). Autonomy in Xinjiang: Han nationalist imperatives and Uyghur discontent (PDF). Political Studies 15. Washington: East-West Center. p. 4. ISBN 1-932728-20-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- 1 2 Dillon, Michael (2004). Xinjiang – China's Muslim Far Northwest. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 51. ISBN 0-415-32051-8.

- ↑ Dwyer, Arienne (2005). The Xinjiang Conflict: Uyghur Identity, Language Policy, and Political Discourse (PDF). Political Studies 15. Washington: East-West Center. p. 2. ISBN 1-932728-29-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Bovingdon, Gardner (2005). Autonomy in Xinjiang: Han nationalist imperatives and Uyghur discontent (PDF). Political Studies 15. Washington: East-West Center. p. 19. ISBN 1-932728-20-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "China's Minorities and Government Implementation of the Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law". Congressional-Executive Commission on China. 1 October 2005. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

[Uyghurs] live in cohesive communities largely separated from Han Chinese, practice major world religions, have their own written scripts, and have supporters outside of China. Relations between these minorities and Han Chinese have been strained for centuries.

- ↑ Sautman, Barry (1997). "Preferential policies for ethnic minorities in China: The case of Xinjiang" (PDF). Working Papers in the Social Sciences (32). Hong Kong University of Science and Technology: 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- 1 2 Moore, Malcolm (7 July 2009). "Urumqi riots signal dark days ahead". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ Bovingdon, Gardner (2005). Autonomy in Xinjiang: Han nationalist imperatives and Uyghur discontent (PDF). Political Studies 15. Washington: East-West Center. pp. 34–5. ISBN 1-932728-20-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ Sautman, Barry (1997). "Preferential policies for ethnic minorities in China: The case of Xinjiang" (PDF). Working Papers in the Social Sciences (32). Hong Kong University of Science and Technology: 29–31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ Pei, Minxin (9 July 2009). "Uighur riots show need for rethink by Beijing". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

Han Chinese view the Uighurs as harbouring separatist aspirations and being disloyal and ungrateful, in spite of preferential policies for ethnic minority groups.

- ↑ Hierman, Brent (2007). "The Pacification of Xinjiang: Uighur Protest and the Chinese State, 1988–2002". Problems of Post-Communism. 54 (3): 48–62. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216540304. S2CID 154942905.

- ↑ Gunaratna, Rohan; Pereire, Kenneth George (2006). "An al-Qaeda associate group operating in China?" (PDF). China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. 4 (2): 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2011.

Since [the Ghulja incident], numerous attacks including attacks on buses, clashes between ETIM militants and Chinese security forces, assassination attempts, attempts to attack Chinese key installations and government buildings have taken place, though many cases go unreported.

- ↑ "'No Rapes' in Riot Town". Radio Free Asia. 29 June 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Beattie, Victor (8 July 2009). "Violence in Xinjiang Nothing New Says China Analyst". VOA news. Archived from the original on 18 December 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Man held over China ethnic clash". BBC News. 30 June 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 "China Says 140 Die in Riot, Uighur Separatists Blamed (Update2)". Bloomberg News. 5 July 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Interview with Dru Gladney. Council on Foreign Relations (9 July 2009). "Uighurs and China's Social Justice Problem" (Podcast). Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Civilians, officer killed in Ürümqi unrest". China Daily. Xinhua News Agency. 6 July 2009. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "World Uyghur Congress behind violence: expert". China Daily. Xinhua News Agency. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Violence Video about Urumqi Riot is Fake". China Radio International. Xinhua News Agency. 29 July 2009. Archived from the original on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 视频-乌鲁木齐"7·5"打砸抢烧严重暴力犯罪事件新闻发布会 [Video-Urumqi "July 5" press conference on the serious violent crime incident] (in Chinese). China Central Television. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original (video) on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ Wu Chaofan (16 July 2009). "Urumqi riots part of plan to help Al-Qaeda". China Daily. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Xinjiang riot hits regional anti-terror nerve". China Daily. Xinhua News Agency. 18 July 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Kadeer, Rebiya (8 July 2009). "The Real Uighur Story". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Sainsbury, Michael (2 January 2010). "The violence has ended in Urumqi but shadows remain in hearts and minds". The Australian. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

There is little doubt [the WUC] helped promote protests, but there is no evidence they fomented violence.

- ↑ "China for unequivocal stand against ethnic separation". The New Nation. 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Epstein, Gady (5 July 2009). "Uighur Unrest". Forbes . Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ↑ 新疆披露打砸抢烧杀暴力犯罪事件当日发展始末 [Xinjiang discloses the development of the violent crime incident on the day of beating, smashing, looting, burning and killing] (in Chinese). 中新网 Chinanews.com.cn. 6 July 2009. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 ""Justice, justice": The July 2009 Protests in Xinjiang, China". Amnesty International. 2 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 We Are Afraid to Even Look for Them: Enforced Disappearances in the Wake of Xinjiang's Protests (Report). Human Rights Watch. 20 October 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ 美新疆问题专家鲍文德访谈 [Interview with American "Xinjiang problem" expert Gardiner Bovingdon]. Deutsche Welle. 23 July 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

Interviewer: 您认为事件的过程已经非常清楚了吗?(Do you think the process of the riots has become clear?)

Bovingdon: 不清楚,而且我觉得可以说很不清楚。(No, it's not clear, and I think you can say it's much unclear.) - 1 2 "Mass arrests over China violence". BBC News. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Demick, Barbara (6 July 2009). "140 slain as Chinese riot police, Muslims clash in north-western city". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 August 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "WUC Condemns China's Brutal Crackdown of a Peaceful Protest in Urumchi City". World Uyghur Congress. 6 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ "World Uyghur Congress' Statement on July 5th Urumqi Incident". World Uyghur Congress. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ Kadeer, Rebiya (20 July 2009). "Unrest in East Turkestan: What China is not telling the media". Uyghur American Association. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ↑ Marquand, Robert (12 July 2009). "Q&A with Uighur spiritual leader Rebiya Kadeer". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

[Kadeer:] I was quite surprised by the loss of so many lives. Initially the protest was peaceful. You could even see Uighurs in the crowd holding Chinese flags. There were women and children, and that seemed at first like a good thing. But the Uighurs were provoked by Chinese security forces – dogs, armoured cars. What has not been noted are the plain clothes police who went in and provoked the Uighurs. My view is that the Chinese wanted a riot in order to justify a larger crackdown; it's an attempt to create solidarity between the Han and the government at a time when there is insecurity. Provoking the crowd justifies that this was a Uighur mob.

- ↑ "Urumqi riots: Weapons prepared beforehand, division of tasks clear". Xinhua News Agency. 21 July 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 Macartney, Jane (7 July 2009). "Riot police battle protesters as China's Uighur crisis escalates". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Kindness found amid the violence |". Shanghai Daily. 9 July 2009.

- 1 2 "Troops flood into China Riot City". BBC News. 8 July 2009. Archived from the original on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ "Traffic curfew lifted, tension remains in Urumqi". China Daily. Xinhua News Agency. 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 13 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 Kuhn, Anthony; Block, Melissa (6 July 2009). "China Ethnic Unrest kills 156". All Things Considered. NPR. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ Clem, Will (8 July 2009). "An eerie silence after lockdown in Kashgar". South China Morning Post. p. A4.

- ↑ Clem, Will (9 July 2009). "Thousands of students detained at college". South China Morning Post. p. A3.

- ↑ Buckley, Chris (5 July 2009). "Three killed in riot in China's Xinjiang region". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ↑ "129 killed, 816 injured in China's Xinjiang violence". Chinaview.cn. Xinhua News Agency. 6 June 2009. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Market reopens in China's riot-hit Urumqi city". Reuters . 22 July 2009. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ↑ Macartney, Jane (7 July 2009). "Chinese Han mob marches for revenge against Uighurs after rampage". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ "Death toll from China's ethnic riots hits 184". Newsday. Associated Press. 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ Duncan, Max (18 July 2009). "China says police shot dead 12 Uighurs this month". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ Wong, Gillian (18 July 2009). "China says police killed 12 in Urumqi rioting". Times Free Press. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ "Innocent civilians make up 156 in Urumqi riot death toll". Xinhua News Agency. 5 August 2009. Archived from the original on 8 August 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ↑ "Bearing Witness 10 Years On: The July 2009 Riots in Xinjiang". The Diplomat . Archived from the original on 7 November 2021.

The official death toll steadily rose, officially reaching 197 people, mostly Han, with 1,600 wounded and 1,000 arrested.

- ↑ "Uighur woman living in France speaks out about alleged Chinese 're-education' camp horrors". ABC News . Archived from the original on 30 March 2021.

Uighur anger boiled over in July 2009 when riots erupted in the regional capital of Urumqi, 197 died (mostly Han Chinese) and over 1,600 were wounded in revolts and attacks over several days, followed by a wave of arrests by the authorities.

- ↑ "Number of injured in Urumqi riot increases to 1,680". Xinhua News Agency. 12 July 2009. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 "7·5"事件遇害者家属将获补偿21万元 [Families of victims of the "July 5" incident will receive 210,000 yuan in compensation]. Caijing (in Chinese). 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Xinjiang doubles compensation for bereaved families in Urumqi riot". Xinhua News Agency. 21 July 2009. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 Foster, Peter (7 July 2009). "Eyewitness: tensions high on the streets of Urumqi". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Police arrests 1,434 suspects in connection with Xinjiang riot". Chinaview.cn. Xinhua News Agency. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ Foster, Peter (7 July 2009). "China riots: 300 Uighurs stage fresh protest in Urumqi". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ↑ Foster, Peter (9 July 2009). "Urumqi: criticism and credit for the Chinese police". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ↑ Fujioka, Chisa (29 July 2009). "Uighur leader says 10,000 went missing in one night". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- 1 2 "Riots engulf Chinese Uighur city". BBC News. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Foster, Peter (7 July 2009). "Han Chinese mob takes to the streets in Urumqi in hunt for Uighur Muslims". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 "Curfew in Chinese city of Urumqi". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Chinese police kill two Uighurs". BBC News. 13 July 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ↑ "Police shoot dead two suspects, injure another in Urumqi". China Daily. 13 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ↑ Clem, Will; Choi, Chi-yuk (14 July 2009). "Conflicting stories emerge after police shoot dead Uyghur pair". South China Morning Post. p. A1.

- ↑ "Exodus from Urumqi as authorities up death toll". France 24. 11 July 2009. Archived from the original on 12 July 2009.

- ↑ "Urumqi mosques closed for Friday prayers". Euronews. 9 August 2009. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- 1 2 Buckley, Chris (10 July 2009). "Chinese police break up Uighur protest after prayers". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ "China reimposes curfew in Urumqi". BBC News. 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- 1 2 Hille, Kathrin (19 July 2009). "Xinjiang widens crackdown on Uighurs". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ↑ Reuters.com. "Reuters.com." China jails Uighur journalist for 15 years – employer. Retrieved on 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "Outspoken Economist Presumed Detained". Radio Free Asia. 8 July 2009. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ "Uyghur Economist Freed, Warned". Radio Free Asia. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ↑ Wines, Michael (23 August 2009). "Without Explanation, China Releases 3 Activists". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ↑ "Minority riots erupt in China's west, media reports 140 deaths". The Indian Express . Associated Press. 6 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 Choi, Chi-yuk; Wu, Vivian (8 July 2009). "Overseas media given freedom to cover unrest, but some areas still out of bounds". South China Morning Post. p. A2.

- 1 2 3 "Report from Urumqi: Thousands of Chinese Troops Enter City Torn by Ethnic Clashes" (video). Democracy Now!. 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009. Discussion of media coverage starting at 26:49, hotel and internet blackout at 29:00.

- ↑ Graham-Harrison and Yu Le, Emma (6 July 2009). "China tightens Web screws after Xinjiang riot". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Internet cut in Urumqi to contain violence: media". Agence France-Presse. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Doran, D'Arcy (5 July 2009). "Savvy Internet users defy China's censors on riot". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 26 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cui Jia (5 November 2009). "The Missing Link". China Daily.

- 1 2 新疆今日起全面恢复互联网业务 [Starting today, Internet service completely restored in Xinjiang] (in Chinese). news.china.com.cn. 14 May 2010. Archived from the original on 17 May 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Martin, Dan (7 July 2009). "156 killed, new protest put down – China". The Advertiser. Adelaide. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ 视频:新疆自治区主席就打砸抢烧事件发表讲话 [Xinjiang chairman delivers message to citizens](video) (in Chinese). QQ News. 6 July 2009. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Xinjiang to speed up legislation against separatism, regional top lawmaker". Xinhua News Agency. 20 July 2009. Archived from the original on 22 July 2009.

- ↑ "After Riots, China to Promote Anti-Separatist Laws". The Jakarta Post. Associated Press. 20 July 2009. Archived from the original on 19 August 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 Wines, Michael (7 July 2009). "In Latest Upheaval, China Applies New Strategies to Control Flow of Information". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 Foster, Peter (7 July 2009). "Uighur unrest: not another Tiananmen". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Propaganda shows of Han-Uygur unity fall flat in Silk Road oasis town". South China Morning Post. Associated Press. 17 July 2009. p. A7.

- ↑ Guo, Likun; Li, Huizi (7 July 2009). "Hu holds key meeting on Xinjiang riot, vowing severe punishment on culprits". Chinaview.cn. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Hu Jin-tao sends Zhou Yong-kang to Xinjiang to direct safety work". China News Wrap. 10 July 2009.

- ↑ Kwok, Kristine (9 July 2009). "Hu's return seen as sign Beijing was caught out". South China Morning Post. p. A4.

- ↑ Pomfret, James (30 July 2009). "China needs new policies after Xinjiang: official". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Jacob, Jayanth (26 July 2009). "Delhi shuts out Uighur matriarch". The Telegraph . Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ "Uighur Kadeer arrives in Tokyo". BBC News. 28 July 2009. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- 1 2 "Australia defies China to host Uighur leader Rebiya Kadeer". The Daily Telegraph. London. 31 July 2009. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Chinese go online to vent ire at Xinjiang unrest". Reuters. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ "Chinese Authorities Blame Internet for Fanning Uighur Anger". VOA News. 8 July 2009. Archived from the original on 20 December 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.