Batesburg-Leesville, South Carolina | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: B-L, BB-LV, The Twin Cities | |

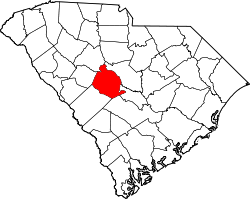

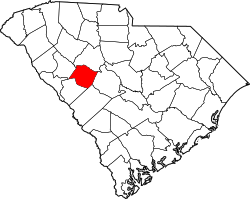

Location of Batesburg-Leesville within South Carolina. | |

| Coordinates: 33°55′05″N81°30′48″W / 33.91806°N 81.51333°W [1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | South Carolina |

| Counties | Lexington, Saluda |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Lancer Shull |

| Area | |

• Total | 8.29 sq mi (21.48 km2) |

| • Land | 8.20 sq mi (21.23 km2) |

| • Water | 0.10 sq mi (0.26 km2) |

| Elevation | 653 ft (199 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 5,270 |

| • Density | 643.0/sq mi (248.28/km2) |

| [4] | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 29006, 29070 |

| Area codes | 803, 839 |

| FIPS code | 45-04300 [5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1253572 [1] |

| Website | www |

Batesburg-Leesville is a town located in Lexington and Saluda counties, South Carolina, United States. The town's population was 5,362 as of the 2010 census [4] and an estimated 5,415 in 2019. [6]

Contents

- History

- Woodard incident

- Law and government

- Mayor

- Town council

- Administration

- Fire department

- Economy

- Top employers

- Poultry industry

- Poultry festival

- Education

- Public schools

- Historic public schools

- Private schools

- Colleges and universities

- Historic colleges

- Library

- Media

- Newspapers

- Radio

- Television

- Geography

- Climate

- Demographics

- 2020 census

- 2000 census

- Notable people

- Athletes

- Musicians

- Governmental and Military

- References

- External links