The New Woman was a feminist ideal that emerged in the late 19th century and had a profound influence well into the 20th century. In 1894, Irish writer Sarah Grand (1854–1943) used the term "new woman" in an influential article, to refer to independent women seeking radical change, and in response the English writer Ouida used the term as the title of a follow-up article. The term was further popularized by British-American writer Henry James, who used it to describe the growth in the number of feminist, educated, independent career women in Europe and the United States. Independence was not simply a matter of the mind: it also involved physical changes in activity and dress, as activities such as bicycling expanded women's ability to engage with a broader, more active world.

Sarah Josepha Buell Hale was an American writer, activist, and an influential editor. She was the author of the nursery rhyme "Mary Had a Little Lamb". Hale famously campaigned for the creation of the American holiday known as Thanksgiving, and for the completion of the Bunker Hill Monument.

Godey's Lady's Book, alternatively known as Godey's Magazine and Lady's Book, was an American women's magazine that was published in Philadelphia from 1830 to 1878. It was the most widely circulated magazine in the period before the Civil War. Its circulation rose from 70,000 in the 1840s to 150,000 in 1860. In the 1860s Godey's considered itself the "queen of monthlies".

Wilma Pearl Mankiller was an American Cherokee activist, social worker, community developer and the first woman elected to serve as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, she lived on her family's allotment in Adair County, Oklahoma, until the age of 11, when her family relocated to San Francisco as part of a federal government program to urbanize Native Americans. After high school, she married a well-to-do Ecuadorian and raised two daughters. Inspired by the social and political movements of the 1960s, Mankiller became involved in the Occupation of Alcatraz and later participated in the land and compensation struggles with the Pit River Tribe. For five years in the early 1970s, she was employed as a social worker, focusing mainly on children's issues.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by herself is an autobiography by Harriet Jacobs, a mother and fugitive slave, published in 1861 by L. Maria Child, who edited the book for its author. Jacobs used the pseudonym Linda Brent. The book documents Jacobs's life as a slave and how she gained freedom for herself and for her children. Jacobs contributed to the genre of slave narrative by using the techniques of sentimental novels "to address race and gender issues." She explores the struggles and sexual abuse that female slaves faced as well as their efforts to practice motherhood and protect their children when their children might be sold away.

The status of women in the Victorian era was often seen as an illustration of the striking discrepancy between the United Kingdom's national power and wealth and what many, then and now, consider its appalling social conditions. During the era symbolized by the reign of a female monarch, Queen Victoria, women did not have the right to vote, sue, or – if they were married – own property. At the same time, women participated in the paid workforce in increasing numbers following the Industrial Revolution. Feminist ideas spread among the educated middle classes, discriminatory laws were repealed, and the women's suffrage movement gained momentum in the last years of the Victorian era.

Kinder, Küche, Kirche, or the 3 Ks, is a German slogan translated as "children, kitchen, church" used under the German Empire to describe a woman's role in society. It now has a mostly derogatory connotation, describing what is seen as an antiquated female role model in contemporary Western society. The phrase is vaguely equivalent to the American "barefoot and pregnant", the British Victorian era "A woman's place is in the home" or the phrase "Good Wife, Wise Mother" from Meiji Japan.

Complementarianism is a theological view in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, that men and women have different but complementary roles and responsibilities in marriage, family life, and religious leadership. The word "complementary" and its cognates are currently used to denote this view. Some Christians interpret the Bible as prescribing complementarianism, and therefore adhere to gender-specific roles that preclude women from specific functions of ministry within the community. Though women may be precluded from certain roles and ministries, they are held to be equal in moral value and of equal status. The phrase used to describe this is 'Ontologically equal, Functionally different'.

The Angel in the House is a narrative poem by Coventry Patmore, first published in 1854 and expanded until 1862. Although largely ignored upon publication, it became enormously popular in the United States during the later 19th century and then in Britain, and its influence continued well into the twentieth century as it became part of many English Literature courses once adopted by W. W. Norton & Company into The Norton Anthology of English Literature. The poem was an idealized account of Patmore's courtship of his first wife, Emily Augusta Andrews (1824–1862), whom he married in 1847 and believed to be the perfect woman. According to Carol Christ, it is not a very good poem, "yet it is culturally significant, not only for its definition of the sexual ideal, but also for the clarity with which it represents the male concerns that motivate fascination with that ideal."

Anti-suffragism was a political movement composed of both men and women that began in the late 19th century in order to campaign against women's suffrage in countries such as Australia, Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States. Anti-suffragism was a largely Classical Conservative movement that sought to keep the status quo for women and which opposed the idea of giving women equal suffrage rights. It was closely associated with "domestic feminism," the belief that women had the right to complete freedom within the home. In the United States, these activists were often referred to as "remonstrants" or "antis."

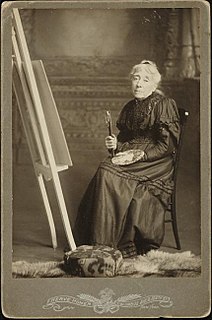

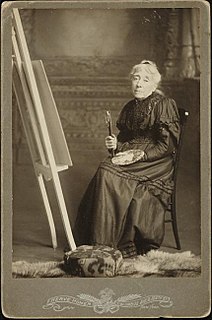

Lilly Martin Spencer was one of the most popular and widely reproduced American female genre painters in the mid-nineteenth century. She primarily painted domestic scenes, paintings of women and children in a warm happy atmosphere, although over the course of her career she would also come to paint works of varying style and subject matter, including the portraits of famous individuals such as suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Although she did have an audience for her work, Spencer had difficulties earning a living as a professional painter and faced financial trouble for much of her adult life.

During the long reign of Queen Victoria over the United Kingdom from 1837 to 1901, there were certain social expectations that the separate genders were expected to adhere to. The study of Victorian masculinity is based on the assumption that "the construction of male consciousness must be seen as historically specific." The concept of Victorian masculinity is extremely diverse, since it was influenced by numerous aspects and factors such as domesticity, economy, gender roles, imperialism, manners, religion, sporting competition, and much more. Some of these aspects seem to be quite naturally related to one another, while others seem profoundly non-relational. For the males, this included a vast amount of pride in their work, a protectiveness over their wives, and an aptitude for good social behaviour. The concept of Victorian masculinity is a topic of interest in the context of Cultural Studies with a special emphasis on Gender studies. The topic is of much current interest in the areas of history, literary criticism, religious studies, and sociology. Those values that have survived to the present day are of special interest to critics for their role in sustaining the 'dominance of the Western male'.

Conduct books or conduct literature is a genre of books that attempt to educate the reader on social norms. As a genre, they began in the mid-to-late Middle Ages, although antecedents such as The Maxims of Ptahhotep are among the earliest surviving works. Conduct books remained popular through the 18th century, although they gradually declined with the advent of the novel.

A gentlewoman in the original and strict sense is a woman of good family, analogous to the Latin generosus and generosa. The closely related English word "gentry" derives from the Old French genterise, gentelise, with much of the meaning of the French noblesse and the German Adel, but without the strict technical requirements of those traditions, such as quarters of nobility.

The Ladies' Magazine, an early women's magazine, was first published in 1828 in Boston, Massachusetts. Also known as Ladies' Magazine and Literary Gazette and later as American Ladies' Magazine, it was designed to be American, and named to separate itself from the Lady's Magazine of London. The magazine was founded by Reverend John Lauris Blake, Congregational minister and headmaster of the Cornhill School for Young Ladies, who desired to set a model for American womanhood.

Terms such as separate spheres and domestic–public dichotomy refer to a social phenomenon within modern societies that feature, to some degree, an empirical separation between a domestic or private sphere and a public or social sphere. This observation may be controversial and is often also seen as supporting patriarchal ideologies that seek to create or strengthen any such separation between spheres and to confine women to the domestic/private sphere.

Ideal womanhood, perfect womanhood, perfect woman and ideal woman are terms or labels to apply to subjective statements or thoughts on idealised female traits.

The eternal feminine is a psychological archetype or philosophical principle that idealizes an immutable concept of "woman". It is one component of gender essentialism, the belief that men and women have different core "essences" that cannot be altered by time or environment. The conceptual ideal was particularly vivid in the 19th century, when women were often depicted as angelic, responsible for drawing men upward on a moral and spiritual path. Among those virtues variously regarded as essentially feminine are "modesty, gracefulness, purity, delicacy, civility, compliancy, reticence, chastity, affability, [and] politeness".

The feminist movement refers to a series of Social movements and Political campaigns for reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such issues are women's liberation, reproductive rights, domestic violence, maternity leave, equal pay, women's suffrage, sexual harassment, and sexual violence. The movement's priorities have expanded since its beginning in the 1800s, and vary among nations and communities. Priorities range from opposition to female genital mutilation in one country, to opposition to the glass ceiling in another.

Jessica Ellen Hayllar was a British artist and painter.