The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

The Mississippi Delta, also known as the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta, or simply the Delta, is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi that lies between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers. The region has been called "The Most Southern Place on Earth", because of its unique racial, cultural, and economic history.

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on plantations and slavery, specifically Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina. After the American Civil War ended in 1865, the region suffered economic hardship and was a major site of racial tension during and after the Reconstruction era.

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement in which a landowner allows a tenant (sharecropper) to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land. Sharecropping is not to be conflated with tenant farming, providing the tenant a higher economic and social status.

The history of the Southern United States spans back thousands of years to the first evidence of human occupation. The Paleo-Indians were the first peoples to inhabit the Americas and what would become the Southern United States. By the time Europeans arrived in the 15th century, the region was inhabited by the Mississippian people, well known for their mound-building cultures, building some of the largest cities of the Pre-Columbian United States. European history in the region would begin with the earliest days of the exploration. Spain, France, and especially England explored and claimed parts of the region.

African-American history started with the arrival of Africans to North America in the 16th and 17th centuries. Formerly enslaved Spaniards who had been freed by Francis Drake arrived aboard the Golden Hind at New Albion in California in 1579. The European colonization of the Americas, and the resulting Atlantic slave trade, led to a large-scale transportation of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic; of the roughly 10–12 million Africans who were sold by the Barbary slave trade, either to European slavery or to servitude in the Americas, approximately 388,000 landed in North America. After arriving in various European colonies in North America, the enslaved Africans were sold to white colonists, primarily to work on cash crop plantations. A group of enslaved Africans arrived in the English Virginia Colony in 1619, marking the beginning of slavery in the colonial history of the United States; by 1776, roughly 20% of the British North American population was of African descent, both free and enslaved.

The Black Belt is a region of the U.S. state of Alabama. The term originally referred to the region's rich, black soil, much of it in the soil order Vertisols. The term took on an additional meaning in the 19th century, when the region was developed for cotton plantation agriculture, in which the workers were enslaved African Americans. After the American Civil War, many freedmen stayed in the area as sharecroppers and tenant farmers, continuing to comprise a majority of the population in many of these counties.

The Antebellum South era was a period in the history of the Southern United States that extended from the conclusion of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. This era was marked by the prevalent practice of slavery and the associated societal norms it cultivated. Over the course of this period, Southern leaders underwent a transformation in their perspective on slavery. Initially regarded as an awkward and temporary institution, it gradually evolved into a defended concept, with proponents arguing for its positive merits, while simultaneously vehemently opposing the burgeoning abolitionist movement.

South Carolina was one of the Thirteen Colonies that first formed the United States. European exploration of the area began in April 1540 with the Hernando de Soto expedition, which unwittingly introduced diseases that decimated the local Native American population. In 1663, the English Crown granted land to eight proprietors of what became the colony. The first settlers came to the Province of Carolina at the port of Charleston in 1670. They were mostly wealthy planters and their slaves coming from the English Caribbean colony of Barbados. By 1700 the colony was exporting deerskin, cattle, rice, and naval stores. The Province of Carolina was split into North and South Carolina in 1712. Pushing back the Native Americans in the Yamasee War (1715–1717), colonists next overthrew the proprietors' rule in the Revolution of 1719, seeking more direct representation. In 1719, South Carolina became a crown colony.

The history of the state of Mississippi extends back to thousands of years of indigenous peoples. Evidence of their cultures has been found largely through archeological excavations, as well as existing remains of earthwork mounds built thousands of years ago. Native American traditions were kept through oral histories; with Europeans recording the accounts of historic peoples they encountered. Since the late 20th century, there have been increased studies of the Native American tribes and reliance on their oral histories to document their cultures. Their accounts have been correlated with evidence of natural events.

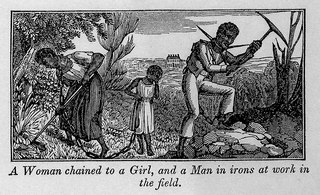

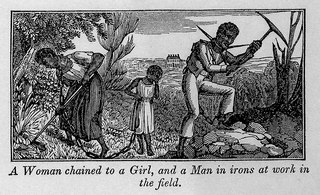

Living in a wide range of circumstances and possessing the intersecting identity of both black and female, enslaved women of African descent had nuanced experiences of slavery. Historian Deborah Gray White explains that "the uniqueness of the African-American female's situation is that she stands at the crossroads of two of the most well-developed ideologies in America, that regarding women and that regarding the Negro." Beginning as early on in enslavement as the voyage on the Middle Passage, enslaved women received different treatment due to their gender. In regard to physical labor and hardship, enslaved women received similar treatment to their male counterparts, but they also frequently experienced sexual abuse at the hand of their enslavers who used stereotypes of black women's hypersexuality as justification.

The history of slavery in Kentucky dates from the earliest permanent European settlements in the state, until the end of the Civil War. In 1830, enslaved African Americans represented 24 percent of Kentucky's population, a share that declined to 19.5 percent by 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. Most enslaved people were concentrated in the cities of Louisville and Lexington and in the hemp- and tobacco-producing Bluegrass Region and Jackson Purchase. Other enslaved people lived in the Ohio River counties, where they were most often used in skilled trades or as house servants. Relatively few people were held in slavery in the mountainous regions of eastern and southeastern Kentucky, where they served primarily as artisans and service workers in towns.

The African slave trade was first brought to Alabama when the region was part of the French Louisiana Colony.

Pigford v. Glickman (1999) was a class action lawsuit against the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), alleging that it had racially discriminated against African-American farmers in its allocation of farm loans and assistance from 1981 to 1996. The lawsuit was settled on April 14, 1999, by Judge Paul L. Friedman of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. To date, almost $1 billion US dollars have been paid or credited to fewer than 20,000 farmers under the settlement's consent decree, under what is reportedly the largest civil rights settlement until that point. Due to delaying tactics by U.S. government officials, more than 70,000 farmers were treated as filing late and thus did not have their claims heard. The 2008 Farm Bill provided for additional claims to be heard. In December 2010, Congress appropriated $1.2 billion for what is called "Pigford II," settlement for the second part of the case.

Plantation complexes were common on agricultural plantations in the Southern United States from the 17th into the 20th century. The complex included everything from the main residence down to the pens for livestock. Until the abolition of slavery, such plantations were generally self-sufficient settlements that relied on the forced labor of enslaved people.

The United States exports more cotton than any other country, though it ranks third in total production, behind China and India. Almost all of the cotton fiber growth and production occurs in the Southern United States and the Western United States, dominated by Texas, California, Arizona, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana. More than 99 percent of the cotton grown in the US is of the Upland variety, with the rest being American Pima. Cotton production is a $21 billion-per-year industry in the United States, employing over 125,000 people in total, as against growth of forty billion pounds a year from 77 million acres of land covering more than eighty countries. The final estimate of U.S. cotton production in 2012 was 17.31 million bales, with the corresponding figures for China and India being 35 million and 26.5 million bales, respectively. Cotton supports the global textile mills market and the global apparel manufacturing market that produces garments for wide use, which were valued at USD 748 billion and 786 billion, respectively, in 2016. Furthermore, cotton supports a USD 3 trillion global fashion industry, which includes clothes with unique designs from reputed brands, with global clothing exports valued at USD 1.3 trillion in 2016.

Black Southerners are African Americans living in the Southern United States, the United States region with the largest black population.

Black land loss in the United States refers to the loss of land ownership and rights by Black people residing or farming in the United States. In 1862, the United States government passed the Homestead Act. This Act gave certain Americans seeking farmland the right to apply for ownership of government land or the public domain. This newly acquired farmland was typically called a homestead. In all, more than 160 million acres of public land, or nearly 10 percent of the total area of the United States was given away free to 1.6 million homesteaders. However, until the United States abolished slavery in 1865 and the passage of the 14th amendment in 1868, enslaved and free Blacks could not benefit from these acts. According to data published by the National Park Service and the University of Nebraska, some 6000 homesteads of an average of 160 acres were issued to Blacks in the years immediately following the war.

Slavery was legally practiced in the Province of North Carolina and the state of North Carolina until January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Prior to statehood, there were 41,000 enslaved African-Americans in the Province of North Carolina in 1767. By 1860, the number of slaves in the state of North Carolina was 331,059, about one third of the total population of the state. In 1860, there were nineteen counties in North Carolina where the number of slaves was larger than the free white population. During the antebellum period the state of North Carolina passed several laws to protect the rights of slave owners while disenfranchising the rights of slaves. There was a constant fear amongst white slave owners in North Carolina of slave revolts from the time of the American Revolution. Despite their circumstances, some North Carolina slaves and freed slaves distinguished themselves as artisans, soldiers during the Revolution, religious leaders, and writers.

The Black Belt in the American South refers to the social history, especially concerning slavery and black workers, of the geological region known as the Black Belt. The geology emphasizes the highly fertile black soil. Historically, the black belt economy was based on cotton plantations – along with some tobacco plantation areas along the Virginia-North Carolina border. The valuable land was largely controlled by rich whites, and worked by very poor, primarily black slaves who in many counties constituted a majority of the population. Generally the term is applied to a larger region than that defined by its geology.